If human lives are the price we’re paying for development, it may not be worth it: Devashish Makhija, writer of the Young Adult novel, Oonga.

As told to Neha Kirpal. First published in India Currents.

“What rights do these trees have, if the cityfolk make all the laws? And if all these laws are of humans, by humans and for humans, what chance does a tree have? Is it fair to force a tree to make way for a road? A railway line? A building? Who fights for the trees?”

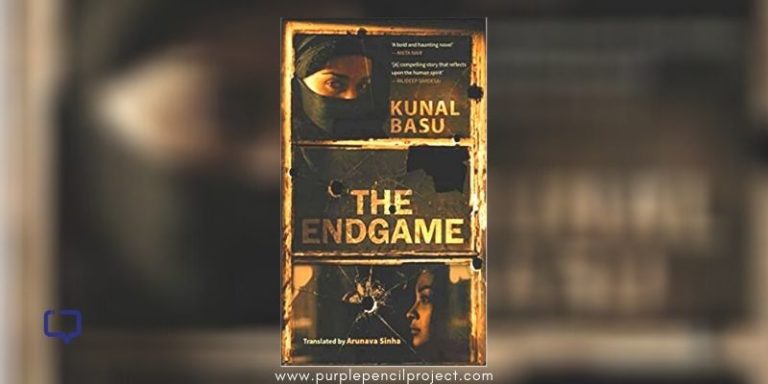

Mining corporations routinely exploit rich forest land in the name of development. The native adivasi tribes, who call the forest their home, suffer as a result. The Naxalites step in to support them, but the government sends CRPF forces to fight them.

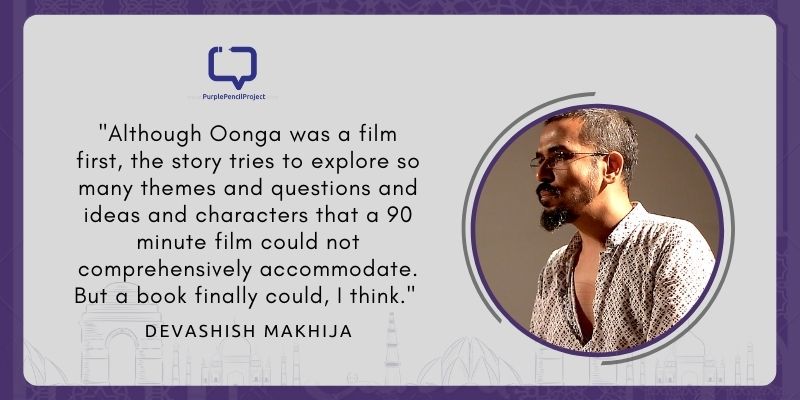

In 2010, filmmaker, screenwriter, graphic artist, fiction writer and poet Devashish Makhija travelled through the tribal belts of Andhra and Odisha, where he decided to write this story, first as a critically acclaimed 2013 film Oonga, and then as a gripping debut novel by the same name. Published by Tulika, the book has recently won the Best Young Adult Fiction book of 2020-21 at the prestigious Neev Book Awards.

The book’s protagonist, Oonga, is a young Dongria Kondh boy. Eager to see a performance of ‘Sitaharan’, he undertakes an epic journey to the city, returning as none other than Lord Rama himself. As heroic Rama, Oonga has the task of defending his village against the demons who have abducted their teacher, Hemla didi. Set in the adivasi village of Pottacheru, the book consists of some extensive descriptions of the deep dark jungles—complete with various sights, sounds and delights. Through the lens of mythology, the book also highlights several relevant issues of our times.

In this exclusive interview, Makhija spoke to us among other things about the inspiration behind Oonga, the research that went into the film and the book, and what he hopes people take back from the story.

How did you decide to make Oonga, the film and then write the book based on it?

Devashish Makhija: The story of Oonga finds its seed in a small anecdote I heard while in Koraput, Orissa. Sharanya Nayak, the local head of Action Aid there told me how she had taken a group of adivasis to watch a dubbed version of Avatar. They hollered and cheered the Na’vi right through the film as if they were their own fellow-tribals fighting the same battles they were. They felt like it was their own story being shown on that screen. But they were shocked when the film ended. It ended ‘happily’! The group of adivasis though, so many years later, were still fighting the same battles, and losing. Something about that not being reflected in Avatar distressed them. When we conceived the story of Oonga, he was to run off to go watch Avatar in the nearby town, and return convinced that he was a ‘Na’vi’ and could save his village from pillaging the way the Na’vi did. But of course in the real world, things don’t play out like they do in the movies. We replaced Avatar with its own source material—the Ramayan—as we developed the story further.

Although Oonga was a film first, the story tries to explore so many themes and questions and ideas and characters that a 90 minute film could not comprehensively accommodate. But a book finally could, I think.

You might ask then why was it written as a Young Adult novel?

I consider my ‘stories’ the ‘people’s perspective’. People cannot write history books; those in power do. And history books end up being the primary record of information of our times for future generations. It’s dangerous that any other perspective but the ruling regime’s is always missing from the history books. And this has been the case since time immemorial. It is in storytelling that we can document the flip perspective – of the people… of those being marginalised. I see myself as a chronicler of this counter-perspective before I see myself as a storyteller even. Young adults will be the decision makers of tomorrow. And I’m trying to do my bit to help them travel into tomorrow armed with both sides of the argument – the side they will receive with almost a military lack of choice from their curriculum; and the side they will actively choose to receive from stories like Oonga, outside their curriculum.

Give our readers the sense of the research that went into this project?

Devashish Makhija: Adapting real life experiences into fiction comes with a very different set of challenges from coming up with a story entirely from one’s imagination. More so if these real life narratives are playing out in the real world even as we speak. A story rooted in the ‘current affairs’ of the nation comes with a long list of responsibilities and caveats. With Oonga, I could not be irresponsible with my stance on an issue which has been tearing the nation’s fabric to shreds for a while now, although invisible to most of metropolitan urban India. It is not an event from the past, like say a story like Black Friday was. It is a narrative unfolding in the real world even while this story of Oonga is being told. As a storyteller, I cannot presume an eventuality for the real world situation. All I can do is to present my stance on the matter – that if human lives are the price we’re paying for ‘development’, it may not be worth it.

The characters populating such a story, is where everything is at then. For which I dipped into real life.

Some examples…

The idea of making Hemla, a tribal schoolteacher who finds herself stuck in the crossfire between the CRPF and the Naxalites, was inspired in part by the case of Soni Sori. It helped us explore the heartbreaking helplessness of someone who decides to not resort to violence even though the only language being spoken on either side is of the gun.

Pradip and Sushil, the CRPF jawaans – one older and cynical, the other a fresh recruit, and always bewildered – find their origins in a little incident I was party to. In February 2010, I footed it through the tribal belt of south Orissa and north Andhra with the photojournalist Javed Iqbal, and documentary filmmaker Faiza Ahmad Khan. Most CRPF camps there had been set up in school premises, just like in Oonga. Skeptical of the queries we might encounter at such camps, we steered clear of most of them. Passing by one in Malkangiri, we were approached by a jawaan. Surprisingly, the first thing he said to Javed was that there was no water in the camp, and the jawaans had to go fetch some from the tube well in the nearby Adivasi village. And that scared him. That was the last thing we thought he’d be. He requested Javed to write about their plight too. That is when it struck me how every single person, on each side of this conflict, could be a victim in some way of a larger cycle of greed and violence.

I dipped into the real world for elements / characters / incidents / details to be able to paint the narrative with the colours of truth.

But HOW MUCH TRUTH IS TRUE ENOUGH? That is a subjective battle we must all fight in whichever way we deem best.

Too much research can dull the ‘accessibility’ of what could be an entertaining story. But too little research can make it appear disconnected from the very reality the story seeks to take a stance on. The answer, therefore, lies in striking a balance. And there is no formula for that. We keep chipping away at it till we ‘sense’ the balance has been struck.

What message do you hope readers can take back from this book?

Devashish Makhija: There are some things in life we don’t think about often and deeply enough. Our daily lives always get in the way. Death, injustice, our anthropocentrism, our capacity for hate, our very imbalanced view of development… I like raising questions about these through my stories. Generally, I never have a solution or an answer. I simply share with the viewer my own heartburn, hoping that they will be haunted by these questions once they emerge from my stories, and keep asking them too.

All storytellers harbour delusions of grandeur, hoping to affect people enough to get them to question status quo in larger numbers to effect social, political, anthropological change. We see dreams of this happening when we write our stories and create our art. But can an artist or a storyteller achieve that? Like a policymaker or political leader can? Who knows. I’m not holding my breath for it. All I can say for sure is that I create my work this way because if I didn’t put my unrest and heartache and rage and questions and protest into my stories, I’d self-destruct. I do this so I can get some sleep at night, however disturbed.

You are a film director, screenplay writer, graphic artist, short story writer, poet and author. Which do you enjoy the most and why?

Devashish Makhija: Impossible to choose one over the other. Instead allow me to share the different things that I derive from these different mediums.

A novel is a gargantuan beast.

In a short story, a children’s picture book or a short film, I don’t have the liberty of character establishment. I often need to get into the thick of the action almost as soon as the story begins. Also, a short story cannot ‘end’ in a conventional way. Closing the loop neatly in a short story is almost impossible given how little time we’ve spent with the characters. It becomes very important there to choose very carefully the ‘portion’ of the characters’ journey I want to make the story about.

The other thing this allows for then in the shorter mediums – short story, children’s book, short film – is multiple revisits by the reader/viewer. A short story or children’s book could be like a favourite song that you can play again and again. A novel demands much more time and attention and investment to provide this kind of a relationship with the reader.

I consciously approach a shorter format story in a way that the narrative doesn’t close its loop by the end. Questions stay unanswered. Characters stay partially undiscovered. The story feels like it could go on.

But with a novel like Oonga, each character has his/her own complete arc, even as the story has one of its own. I map each arc beforehand, so I know their intersectionalities, their convergences and divergences, before I even start the physical writing process. The abruptness of a wildly open-end can leave the reader very dissatisfied in a novel, because I have drawn them into a ‘world’ that they inhabit with the characters for over 300 pages.

Whereas the shorter storytelling forms allow me to undertake more of an exploratory creative process, a novel needs all the engineering, cartography, universe-building skills I can muster. Whereas the shorter forms end up mostly being about the character(s), a novel like Oonga needs to be about a well-charted story, an amply-detailed universe as well as deeply-plumbed characters.

The mind, the heart and the eye need to be prepared differently for different mediums of storytelling. And I enjoy them all, undertaking different processes for each, and taking away different joys and satisfactions from them.

Who or what are some of your biggest inspirations?

Devashish Makhija: I’m not sure if art or literature or cinema are my biggest inspirations. My stories are political mostly. And so the real world and its people and other creatures are probably my biggest inspiration. So I can share some names of books which helped inform Oonga, that I feel every Indian needs to read to initiate some understanding and empathy for the very complex and very heartbreaking crossroads that the Indian tribal finds themselves at for decades now, with no clear resolution in sight that precludes their own prerogatives.

- Junglenama by Satnam

- Hello Bastar by Rahul Pandita

- The Burning Forest by Nandini Sundar

- Red Sun by Sudeep Chakravarti

And this one book that I feel should be compulsory reading for every citizen, to realise what we are capable of if we only acknowledge, understand and exercise our rights to fairness at all times:

The RTI Story by Aruna Roy

What are you working on next (films, writing, etc.)?

Devashish Makhija: All my stories are really hard to find backing for – whether it be books or films. I’ve got about 15-16 stories and screenplays that I’m pitching around constantly, trying to turn them into films. The films I make get watched by a very niche audience. They almost never make their money back. So it takes me three-four years to find backing for a film. Even so, Manoj Bajpayee and I are trying to set up another film together, after Bhonsle. And I made two short films last year that are ready now, and need to find a way to get out into the world this year.

I’m hoping that Oonga does well. So that I can actually drop everything and write my next novel, which is ready inside my head and heart. It is a lot more personal. It’s mostly about a night on the 6th of December, 1992 in a mohalla in Calcutta… a night that shaped me in ways I could not imagine then.