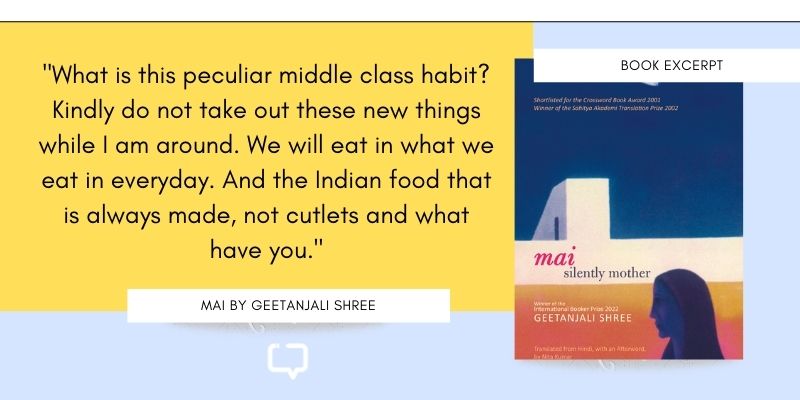

A book excerpt from the author’s debut novel

It had been our complaint since childhood. ‘Speak up mai. Fight back. Become what you want to be.’ Being what she was, mai was actually nothing. She was a stooping, dumb, frightened shadow who moved only upon others’ directions. We were full of pity. And were also somewhat put off. It was someone else we could not forgive who had let this person become ‘mai’.

Because ‘mai’ was the synonym of ‘not becoming’. Why was mai not permitted to become, to be real? We would never be mai. We would never stay ‘not made’. This was our profound belief, our bitter struggle, our life. When a loose, old-fashioned sari with the end over the right shoulder appeared on an invisible body in my pictures, Judith again made a comment. That this person lost in this formless void is someone who did not ‘become’. Who never got the right to ‘be’. Who, if she exists, exists in her ‘not being’. Her absence is her existence. Judith advised me to name that picture ‘Conflict’. But she wanted me to make, on that same canvas, another formless body that had a void for a face, but in the void appeared a faint shadow.

Nothing need be too clear but there should be marks of a deep wound. In childhood I got such a mark. The lights had suddenly gone in the middle of a thunderstorm. I thought of a trick to be played in the light of the candle and the lantern. I was in front, Subodh behind. I hid behind the door. By chance Subodh’s shadow came before him, shivering in the gleam of lightning. I saw it and jumped forwards with a ‘boo!’ At that instant Subodh opened the wood- framed screen door, breaking my skull. ‘It’s symbolic,’ said Judith. When Judith came to our house she would stare at everything.

She tasted, her mouth puckering, the sour beans hanging from the tamarind tree. She loved it when mai rolled rotis. She went and sat by babu when he did his hawan. She stared at Bhondu when he slapped and downed his tobacco. She asked hundreds of questions about the absence of toilet paper. Agreed, she said, that water is the best cleanser, but what do you do with the wetness of your body? We were surprised that we had never thought of this nor had it ever occurred to us that water was dripping from us. Judith stayed many days with us but she was not keen to look around in the town outside. It was we who sometimes pulled her to the river, or to someone’s house, or to the old neighbourhoods.

The mango crop was spectacular that year and babu took everyone to Raghav kaka’s village where, sitting in the orchard, a bucket in front in the style of dada, we had dozens of local mangoes cooled in water. Babu liked to eat his mangoes sliced round with a spoon to pick the meat, but local mangoes insist on being eaten the local way. Babu was not displeased with Judith’s visit as long as he could believe that it was Sunaina’s English friend visiting. But Subodh could not care less—he took her around everywhere with abandon, disappeared with her on the roof, talked with her in her room late into the night, coming out only after everyone had fallen asleep. Babu asked mai repeatedly, ‘Have you asked? Find out.

He is your son. These foreign girls. Yesterday she was smoking.’ Mai did not find out. She liked Judith’s sociable personality. Judith wanted the board and rolling pin, ‘I’ll make the rotis.’ Mai loved it. She made her all kinds of special dishes. Mai took out the ‘unbreakable’ tea set from the box the day that Judith came. ‘Make tomato and cucumber sandwiches, and rolls,’ said babu. ‘And listen. Keep the tea separate and milk and sugar separate. We will make it there.’ Hardeyi brought everything carefully to the drawing room.

She had also been given a thousand instructions: stand like this, pick up the plates when the spoons are like this, serve from this side. We were embarrassed. The hollow sound of forks and knives on those strange synthetic plates kept ringing in our ears. I tried to joke. ‘Watch, Judith, this is the flat sound of your kind of crockery.

When you eat in our metal plates you will hear music.’ Subodh gave us a talking-to later. ‘What is this peculiar middle class habit? Kindly do not take out these new things while I am around. We will eat in what we eat in everyday. And the Indian food that is always made, not cutlets and what have you.’ Mai looked to babu who began to stammer, ‘I never said…’— and mai looked down silently. Babu wanted that mai should ask, find out. We wanted that mai should speak, speak out. ‘Speak what? What do you mean?’ asked mai. ‘I don’t have anything to say.’

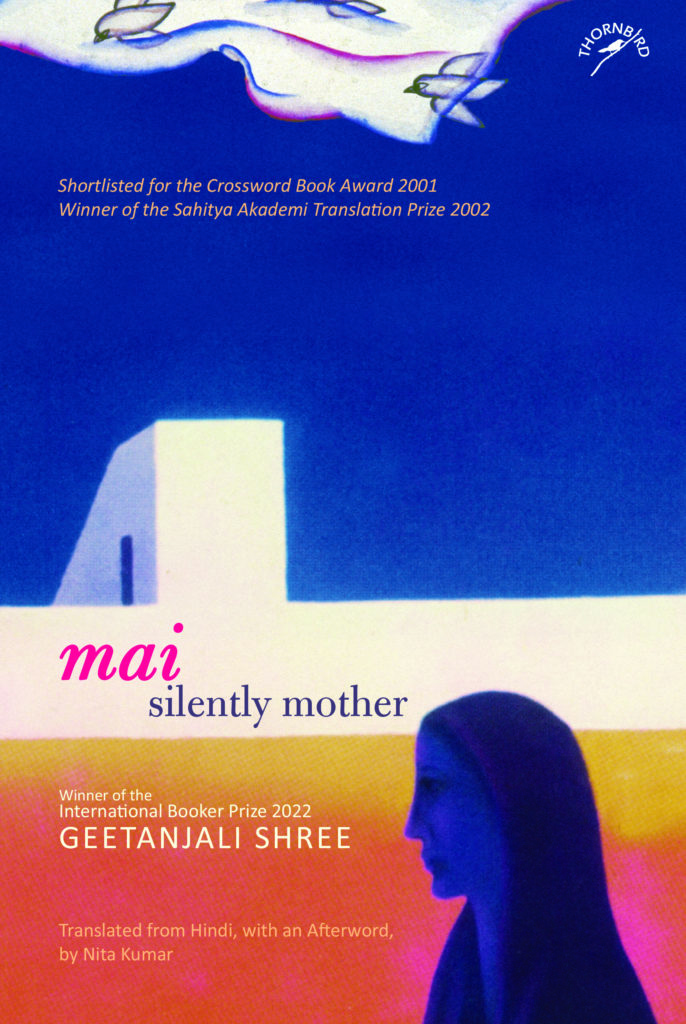

Title: mai silently mother

Author: Geetanjali Shree | Translator: Nita Kumar

Publisher: Niyogi Books

Blurb: Behind the walls of a house in a North Indian town a whole world thrives—of the joint family, their attendants, their visitors. Three generations of women and their men live different strategies of adjustment and achievement to accommodate or challenge patriarchy. They seem to fit in recognised frames, but what are the subtle machinations behind the apparent stereotypes? It is that which the novel uncovers, in a tale told in deceptively simple terms, using smells, sounds, tastes and flavours, scenes and tiny signs, and incidents of a daily and ordinary existence to build, weave by weave, a rich and layered tapestry, saying always more than is apparent. At the centre is mai, the mother, seemingly weak and silent, but it is she who holds together the subtle patterns of relationships and agencies, and quietly carves out a life for herself as also for those around. Her New Age children are obsessed with rescuing her from the ‘prison’ and escaping themselves; but as the story unfolds, any simplistic notion of bondage and freedom goes for a toss. Profound stories of love and loss are lightly delivered.

Price: Rs. 395 || Pages: 224