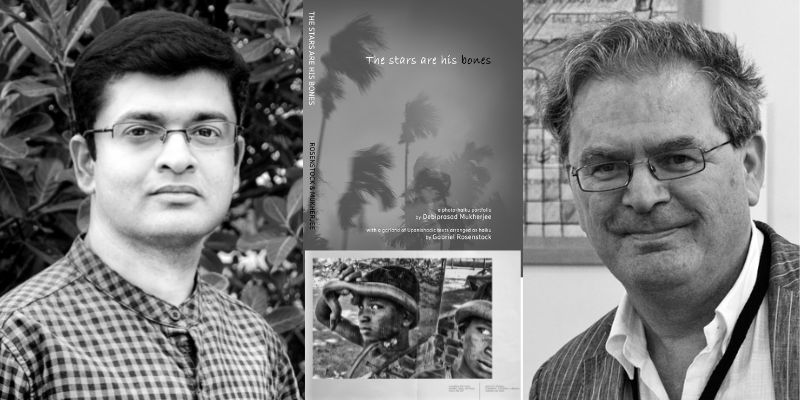

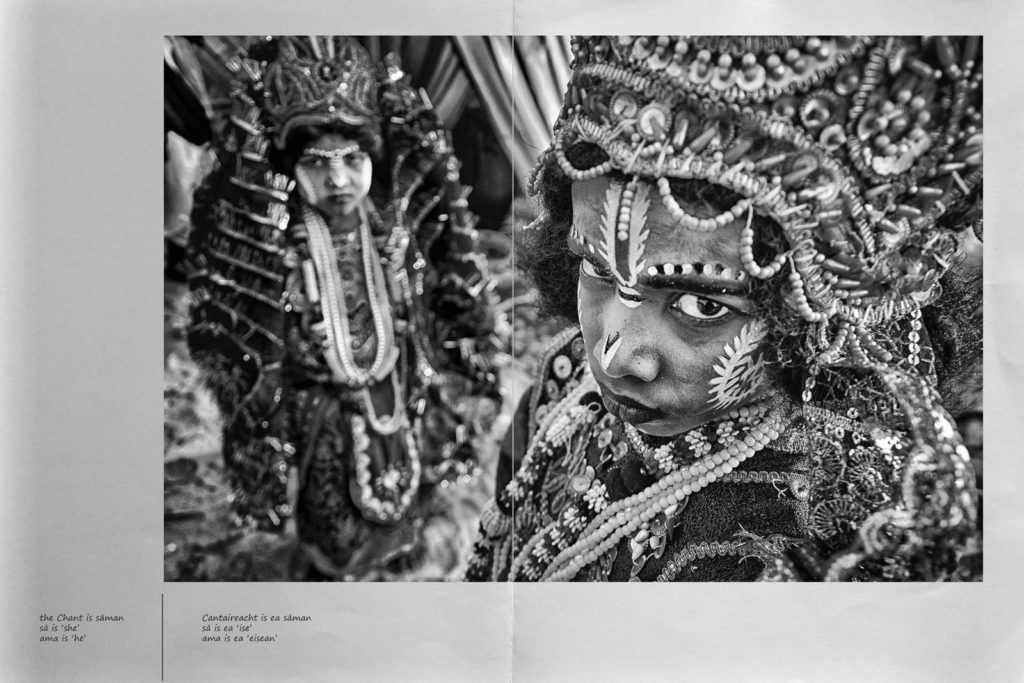

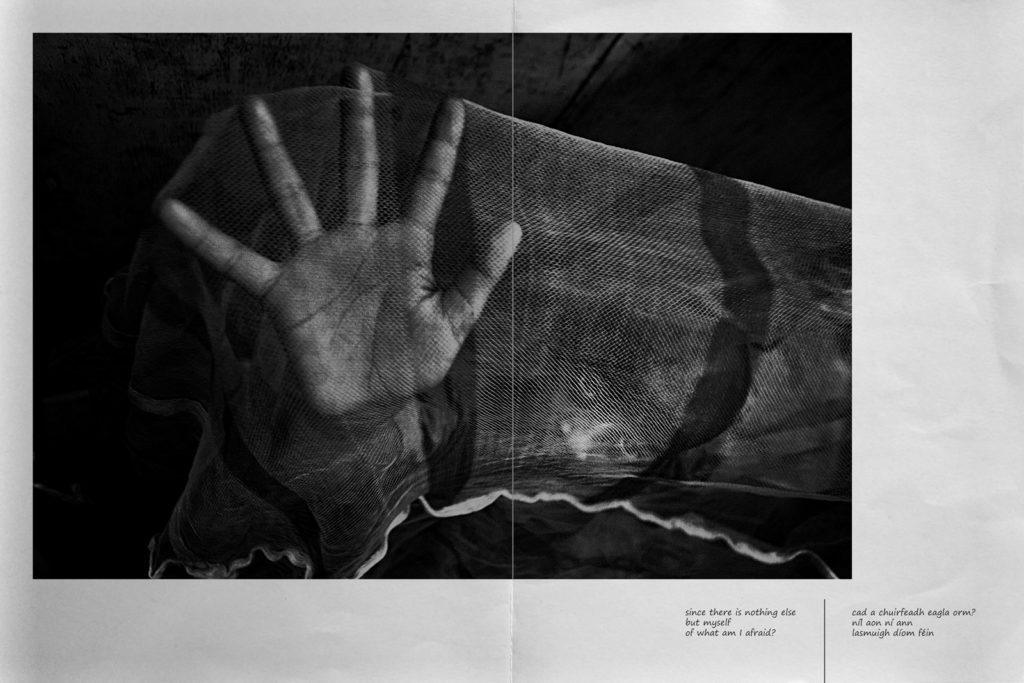

Haiku inspired by the Upanishads, photographs that capture Calcutta. One written by an Irish poet in Irish and English, one clicked by an Indian photographer. Seemingly disconnected dots are joined beautifully by Irish poet Gabriel Rosenstock and Kolkata-based photographer Debiprasad Mukherjee, whose latest collaboration, The Stars are His Bones, a photography-haiku collection that takes the text-visual collaboration to the next level. We caught up with the artists over email, about cross-cultural collaborations, the universal wisdom of art, what reading means for an art book, and much more. Excerpts:

How does a photographer and poet meet? You two have had a longer association that this book: can you talk about that a little, about your artistic relationship?

Gabriel Rosenstock: I have been responding to art photography with haiku for almost half a century. You can see samples on my blog, bilingual, or multilingual, responses to the landscape photography of American photographer Ron Rosenstock (no relation). I also enjoy responding to artwork with tanka, 5-line poems in 5-7-5-7-7 syllables (31 syllables in all) and a recent book with Ron is Daybreak, Poem-Prayers for Prisoners.

I try to keep abreast with what is happening in the world of fine art photography.

I came across the outstanding photography of Debiprasad Mukherjee in one of the photography blogs that I subscribe to and we made contact and ‘clicked’. We published a few collaborations together in The Irish Times and in the universally admired blog The Culturium, and eventually we wanted to do a book together. I’m delighted to say that artwork from the book, The Stars are His Bones will feature at the Belfast Photo Festival in June 2023. These things take a lot of forward planning.

How did your artistic relationship, as well as the photography-haiku book Stars are His Bones, come about?

Gabriel Rosenstock: I came across an early translation of The Upanishads which meant that the text was in Public Domain. Robert Ernest Hume (1877 -1948) was actually born in India. There have been many translations into English since then, of course, but there was something about Hume’s version that attracted me. Just because a translation is old doesn’t mean it should be discarded. The idea came to me that selections from Hume’s Upanishads could have a strange impact if appearing on the page as “found haiku”, matched with Debiprasad’s contemporary but timeless images.

I want to direct the question to the act of ‘reading’. When one thinks of it, you imagine lots of words, lots of text and plot and the like. When you think of photographs and the combination with words, how does the act of reading change for you? I think of this also because of how visual our stories have become – with the rise of the digital.

Gabriel Rosenstock: Yes, everybody is conscious of how so many texts have become minimalistic: flash fiction, sudden fiction, microfiction, postcard fiction, etc. –haiku, haibun and tanka also fit nicely into this demand for shorter texts. But, of course, short fables have been around since the time of Aesop and earlier; indeed, Aesop may have heard some Indian fables from fellow- Greeks who came back from Alexander’s visit to India! This European-Indian encounter has been going on for a long time. As far as I know, Buddhism had only abstract symbols such as the wheel and that we owe the glory of his sculpted face to the influence of the Greeks.

Getting back to short forms of literature: parables, made famous by Jesus, have been around for a long time as well. Indeed, aphorisms and proverbs are a form of short literature ijn themselves, undoubtedly.

You describe the haiku in the book as ‘found’? Could you talk a little more about why ‘found’? How did you choose the lines to ‘match with’ (for lack of a better word) with the photograph?

Gabriel Rosenstock: A ‘found’ poem or a ‘found’ haiku is simply something that is extracted from an existing text to take on a life of its own as a poem or a haiku. Let me open Palgrave’s Golden Treasury at random. I see a poem before me by Sir Walter Scott. I am going to change the first two lines into a three-line ‘found’ haiku. Watch!

the sun upon the lake

is low . . .

wild birds hush their song

So, we have a complete ‘found’ haiku there, extracted from an existing poem. If you like haiku, you might prefer those lines to the complete poem!

It can be simply a matter of re-alignment, retaining the original text word for word, or cutting out ‘connective tissue’ – the definite article for instance. The result is a different experience of the isolated text as something complete in itself (though it has undergone surgery). This can be done with texts from diaries, travel writing, novels, poems, sermons and so on.

Debiprasad matched the images beautifully to the text (without being too literal).

Why the Upanishads? What is it about the translation or the Upanishad itself that drew you to it?

Gabriel Rosenstock: The Upanishads are incomparable as wisdom literature. Our own national (Anglophone) poet, W. B. Yeats, did an edition of the Upanishads at a time when Theosophy was fashionable among the literary classes of London and Dublin. Yeats originally planned to travel to India to undertake the task but health reasons prevented him.

How did you curate the photographs that would become a part of the project? Were they any works or books that inspired you to take up the project?

Debiprasad Mukherjee: The curation of this project was somehow different than other typical photo stories. Both the photographic curation & haiku ran in parallel & spontaneously. When Gabriel shared some of his magical haikus with me, instantly it provoked certain thoughts in me which was the driving factor to select, edit the photographs, and even I went on creating new content to respond to his poetic thoughts. I guess the other way round was also true. Based on the flow of the curated photographs, Gabriel also added or modified certain haikus to create his magic. It was like musical “sawal-jawab” which took place effortlessly.

Regarding inspiration, I really doubt whether there is any such collaboration exists previously where real life documentary photographs are used to collaborate with Upanishad-based haiku or even any other form of poetry. So, the if there exist any single book that inspired us, is the set of Upanishads only which helped us to realize our own “atman” (soul or self) with respect to deep spiritual essence in all realities.

How does the Upanishad, an ancient heavy text, lend itself to the brevity of the haiku. Do you see it as the loss of context, when you translate from the ancient to the modern, or even from the one language to another, or as an extraction of meaning? Could you throw some light on this?

Gabriel: Why describe the Upanishads as ‘ancient and heavy’? Delve into the Upanishads and your life will be lightened! Why talk of ‘loss of context’? The Self is without context; the Self in me, the Self in you, the Self in the forest sages is one and the same and needs no context.

Nothing in the whole world is as important as knowing the nature of the Self. The German philosopher Schopenhauer, who only read a translation of a translation (in Latin), said, ‘In the whole world there is no study so beneficial and so elevating as that of the Upanishads.’