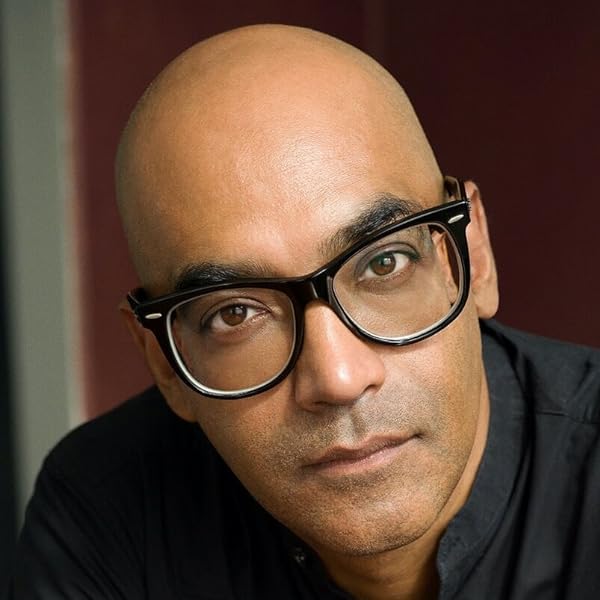

Samruddhi recommends The Light at the End of the World by Siddhartha Deb as your next read, promising that it will jolt you awake and recalibrate your worldview.

If I were to encapsulate The Light At the End of the World by Siddhartha Deb in a few words, it would be a tremendous feat- which makes this review difficult to pen down. One of the quotes Deb mentions before beginning his first story, is by an anonymous political prisoner: ‘India is not a nation. It’s a prison house of all possible nations.’

This novel, too, is not simply a novel but a prison house -or an ever-expanding paradise of ideas (it depends on your perspective)- A compilation of four narratives set in different periods and at times, fictional Indian cities around four protagonists, each as unique as the worlds they inhabit.

We encourage you to buy books from a local bookstore. If that is not possible, please use the links on the page and support us. Thank you.

An Amalgamation of four voices and their worlds

“The fog is a paintbrush, erasing the marks on an old, much-used canvas, erasing the streets, the cars,…, erasing a nation that has failed by every measure.”

The Light At the End of the World by Siddhartha Deb

In ‘City of Brume’, we’re introduced to the disillusioned journalist, Bibi who has a particular tenacity for survival in an increasingly violent dystopian world rife with extreme inequality that sells a utopian dream with the caveat that ‘nothing is greater than the nation’. Delhi comes alive as a monstrous city of its own making and mind, where everything from Chanakyapuri to Chandni Chowk and Chor Bazaar evokes a sense of dread instead of any nostalgia. Specifically, Deb starts to play with ideas of the ‘Freudian Uncanny’ and creates a kind of eerie tension through Bibi’s daily life, Delhi’s dystopian atmosphere, and Bibi’s almost forgotten old identity and roots.

Everything changes for her when she’s tasked with finding Sanjit, her old partner-in-crime from when they used to chase idealism and ethics through their news stories. Through her journey of finding out whether or not Sanjit is even alive, she faces at first, a mild discomfort, which then progresses to an undiluted volatile sense of horror regarding what the world around her has become and how her exhaustion from chasing the truth along with a deliberate pretense from avoiding this truth later on, has made her complicit not just in the current state of the world but also in Sanjit’s disappearance.

Recommended Reads: In Conversation with S.B. Divya

‘Clautropolis: 1984’ is perhaps the most effective satirical piece I’ve read recently. Spliced with an equally humorous and bleak undertone, it introduces an unnamed, experienced assassin who, as his profession suggests, has an unhealthy obsession with violence. Through this narrative, Deb skilfully demonstrates the nature of politics in a nation’s past, present, and future, whether it’s in relation to the Indian landscape or universally.

Storytelling and Characters

Set just weeks before the Bhopal tragedy, an industrial accident in Bhopal’s Union Carbide pesticide plant that killed thousands, Deb deftly breaks open the narrative around the disaster, sold to an ignorant audience to cover the consequences of corporate greed. He also successfully manages a sharp social commentary, resonating with the current political scape, and his ultimate resolution of this assassin, at once, humanises and shatters bigoted ideologies.

‘Paranoir: 1947’ begins with a veterinary student named Das in Calcutta, when India is on the brink of Independence and the bloodiest migration of people in its history. Deb highlights the dichotomy which pervades the Indian Dream even today, which is well expressed in A.K. Ramanujan’s quote: “Sky-man in a hole with Astronomy for a dream, astrology for nightmare”.

And yet, while following Das and his increasingly alarming conviction of being chosen by a secret committee to pilot a sacred Vedic aircraft that will bring humanity peace, at the story’s heart Deb leaves us with the message, that ultimately, it is the pilot who knows the secrets, who steers the vehicle- he has the power to recalibrate, return, reassess and react. And that the most powerful variable in any equation is love.

‘The Line of Faith: 1859’ revolves around a British regiment chasing the last of the mutineers involved in the famous 1857 Sepoy Revolt. This story is perhaps the hardest to categorise as it involves a ‘White Mughal’, magical objects, surrealism, an old myth about Tipu Sultan, and even elements of steampunk and the occult. Deb uses the fantastical setting to lay out the destructive effects of Western Capitalism:

“The two savants spoke of steam-powered iron elephants pulling vast trains of cargoes through wide boulevards, of flying machines powered by clockwork and cities suspended in the air. Factories burst out of farming soil, factories like military machines in their precision and order. The perfume of progress of these factories filled the air and crowds cheered the captains of industry who strode like colossi.”

The Light At the End of the World by Siddhartha Deb

Meticulously constructed, through the regiment’s fantastical journey, Deb shows not just the devastating ruins of colonialism but also how it affects the people who are its cogs and wheels. He also takes obvious inspiration from the Strugatsky brothers and their sci-fi novel, ‘Roadside Picnic’ for the phenomena that affect the British regiment’s sanity and lives.

Siddhartha Deb’s leitmotifs and stylistic conceptualisations

Deb dips his feet frequently into philosophy, magical realism, and fantastically unscientific ideas yet, it is because his research is grounded firmly in history and ironically, science, that the narrative can afford to blur the lines between fantasy, surrealism, and reality to such degrees.

Bibi’s ultimate destination is the fitting location of Andaman Islands which became a penal colony after the Sepoy Revolt and housed political prisoners till World War Two. Here, she finally stumbles onto the vague answer of cybernetics- the complex self-regulating systems of communication in both machines and living beings and asks the reader to draw their own conclusions.

Through recurring motifs of the Kaala Bandar, reprising characters, frequent ‘ghuspetiyas’- a term for infiltrators that modern Indian politics has weaponized, and the feeling of being constantly watched, borrowed from George Orwell’s 1984 which is cleverly woven in the narratives as Bibi’s and the unknown assassin’s experiences, Deb questions the reality in which we exist and how we got here.

Through the breaks in the sanities of his characters, he introduces the idea that if a perspective needs to shift, perhaps the process needs a bit of madness. Yet as dark and harsh as his worlds appear to be, Deb plays a discordant piano note in the last chapter of the story and affirms some hope in the reader that there is indeed, Light at the end of these worlds.

Have you read this expansive, imaginative, kaleidoscopic fever dream in motion? What do you think of it? Drop a comment below and let us know!