Speaking to Shubhangi Swarup, like reading her book, is to leave the parochial behind. It is to be inspired to live as fully and engagingly as possible, to push the boundaries of experiences and consciousness. In this interview for onWriting.in, she talks about life during, before and after Latitudes of Longing, the need for novelists and readers to take the leap of faith into experimental fiction and of course, about storytelling and its joy.

On becoming a writer and her debut novel

Swarup, 36, grew up in Mumbai, got a BA (Honours) in Literature from St. Xavier’s and an M.Sc in Violence, Conflict and Development from SOAS, University of London. “I grew up in a household that valued the intellect, reading and the ability to engage with ideas. I was always being driven by inquiry, curiosity and the desire to learn,” she says, sitting comfortably in her Bandra home.

Ask her on who her literary influences have been, and she takes out a notebook, emanating a sense of deliberate awareness that will reflect throughout the interview. “I find that sometimes what’s on top of my head doesn’t do justice to the questions.”

The list includes the Egyptian writer Naguib Mahfouz, A K Ramanujan’s A Flowering Tree for narrative style, Haruki Murakami and Gabriela Garcia Marquez. “I would call Marquez and Mahfouz, ‘seismic’ influences in my writing. And Murakami’s books are a great course in creating the atmosphere, and stories which rely more on it than plot lines.” Then there’s Ten Thousand Things by Maria Dermout, a Dutch writer, works of filmmaker Hayao Miyazaki, and Japanese, Spanish, and literature from countries in Africa.

Did she always want to be a writer? “Writing is only a medium of expression I have chosen to channel the sense of curiosity I have harboured since childhood. I don’t write for the love of language, and often struggle to express myself, given that English is not a perfect one. But it is the easiest tool I have right now. It is also about context. If I had grown up in a house of sculptors, I may have chosen that medium.”

This sense of curiosity has led her to question the way humans live as largely disconnected from the natural world, to experience the rhythm of dancing, to dabble in virtual reality filmmaking through which she understood sound, to travel and see how political borders could not separate the shared characteristics of the people and the region of the subcontinent, to read and hear stories translated from across the world, and be open and aware of everything around her.

“The initial idea for the novel came from awe, and a sense of disbelief, at how the natural world is so connected in a way we are not, which my mother would often point out. Through tectonic fault lines, snow deserts and tropical islands have an ancient connection.”

We walk on land as it it’s permanent, but what is land today was a sea million of years ago. You don’t have to be a geologist to be fascinated of the fact that Antarctica and India have a shared geological past. I wanted to explore these through my writings, bring them to the foreground.

On researching for her book

Latitudes of Longing is filled with meditations that cross the boundaries of time and consciousness but it is also based in real places, and built on seven years of hard research. How did she marry the two?

Swarup traveled extensively through these years, from Ladakh to Bhutan, Arunachal Pradesh, Myanmar, Kathmandu and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, staying on an average for a month in each place. The research, “helped me situate the stories and find new voices. Several dialogues in ‘Fault’ and ‘Valley’ are real, in the actual tone used by the people I interviewed.”

“Being an artist, you also question how to use research. Is it to promote hegemony, to use it to go on with what is at the top of the pyramid or to seek out other voices?” Thus, once she started writing the novel, she read regionally published literature widely including folktales, memoirs and works of non-fiction. These she then used as a basis for the mythologies she has created in Latitudes of Longing and inspired the tone of each section of the book. The Mourning Turtle, for instance, is based on Burmese folktales.

But writing the book was to go a step beyond journalism, which can be restrictive. “I was seeking without knowing what.” This made her aware of the subtler things; the temperature, the trees, the leaves, the rocks, the insects, “which we think of as generic but are not”. She would go meet the oldest man in the village, or hear a never-ending tale about a rabbit, his evil tail and an old lady from an eight-year-old shepherd in Ladakh or sit at the beach for hours. “There is so much to observe.”

“When I was in Rangoon, I was living alone for a week to ten days and there was a baby lizard in the house. With no other company, I became incredibly aware of this other life-form I was sharing the space with, and I sort of started looking out for it, much as we would for a cat or a pet in the city. But living in the present, I could feel the same connection with a small creature, without the sense of drama that we need to otherwise acknowledge other life forms.”

The layers came from experiences like these.

Fiction begins where non-fiction ends and you can only make that journey through your imagination.

“For example, I have no background in the earth sciences or natural history, yet a lot of the book is inspired by actual moments in evolution and the journey of continents. I had to teach myself a lot of the principles and concepts. And even after years of researching, and interviewing scientists, eventually I had to close the book, keep the pen down, sit alone and bring it alive in my imagination, much like Girija Prasad dreaming in the first chapter.”

(A fun challenge she posed to us, and you can try your hand at. Here is a link to the Messil Pit Fossil Site which she used as a resource. Guess what it inspired in the book?)

Did she, at any point, doubt about whether she will be able to see it through? “It was never of question of if. I knew I had to write this book. I think as an artist, it is good to have an ambition. It helps you stay committed to your work.”

On metaphysical experiences

Ghosts, clairvoyants, wise old men who can predict earthquakes and a yeti co-exist in this story with the humans, who together transcend the realities we know to be true. Has she had any metaphysical experiences, an encounter with a ghost perhaps?

“I don’t believe in ghosts. But I don’t have to, to be scared of them!”

The ghosts, perhaps came first, in the book. “I was living in Andaman, where every house has a story attached to it. As I was living alone, sleeping at night after listening to these stories, with no electricity, no internet and the rain continuously pouring became a task!” she laughs. It was when she was locked in during the three-day storm that she began writing.

Chanda Devi followed the ghosts. “In India, and even in the subcontinent, you don’t have to go too far to meet a clairvoyant. Every house has one, and Chanda Devi is loosely based on my grandmother (though she denies it to her family, who we hope are not reading this interview!). But again, I was driven by curiosity. Why just people? Why cannot clairvoyants talk to dead animals or trees? I would love to hear their tales.”

On fiction, novelists and readers

She has been influenced by books and films, and has also worked in both mediums. However, when it comes to contemporary fiction, she is “very critical. I think they are too artificially plotted.”

As she has learnt from oral storytelling, “it is not about where it is going and what is happening; one thing can lead to another. It’s about that momentary intrigue and emotion.”

“Current stories told are too restrictive, and adhere to a formula which I suspect comes from films. I don’t want to write a screenplay, which is sometimes what they feel like. Books are books, and are meant to do something different.”

On Twitter, she had asked the question, What is the role of novelists today? “I don’t think I have found the answer fully. But I find it interesting that no one says that novelists should entertain or give us what we want, yet these are the criticisms of so many books that are currently published. As writers, we have to experiment, but it takes two to tango. After this question, I had also asked what is the role of readers today and received far fewer responses. Readers should also take a leap of faith with the novelist. I am grateful to my readers for doing so with my book.”

On her next work

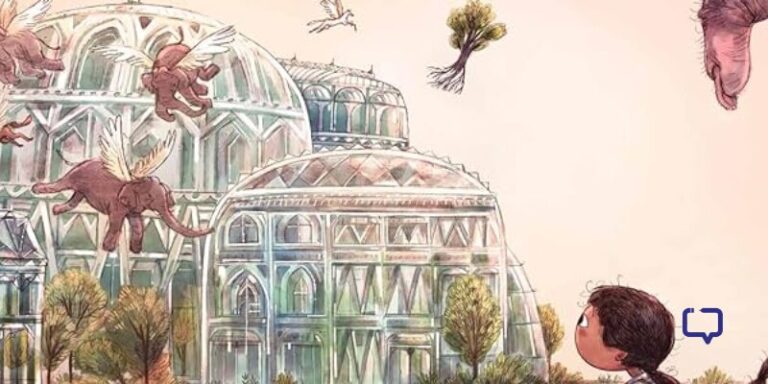

Post the book, she has not taken up any other project, focusing on its marketing and related activities. But now, she is contemplating a non-fiction work about the villages in Ladakh, or a children’s book. “Perhaps a picture book for adults, where they can read a bit and also colour the images.”

Shubhangi Swarup is the author of Latitudes of Longing, which is among the five books shortlisted for the JCB Prize for Literature, the winner of which will be announced on October 24, 2018.