India is home to one of the most linguistically diverse populations in the world. According to the 2011 Census, the country recognises 22 scheduled languages. But the reality is far more vivid and rich. Over 1,600 mother tongues are spoken in India, representing centuries of regional, ethnic, and cultural evolution. Languages in India are central to regional identity, political influence, and social integration.

The language politics in India have always played a critical role in shaping these dynamics. The way languages are prioritised or marginalised reflects deeper political strategies that affect both national unity and regional autonomy.

Language in India is intertwined with regional pride, political autonomy, and social cohesion. This connection between language and identity became particularly apparent after independence with the reorganisation of Indian states in the 1950s, mirroring the linguistic boundaries drawn by history.

For many regions, their mother tongue represents a cultural and political assertion and a representation of autonomy within a multilingual democracy. However, the Indian Constitution’s dual-language policy—recognising both Hindi and English as official languages of the Union—right after independence felt like a deaf-mute decision, as if oblivious to the nation’s linguistic plurality. The decision to prioritise Hindi led to tensions across the country, particularly in the southern states, through the upcoming decades.

The language politics in India became even more pronounced during these decades as movements to resist linguistic imposition arose, particularly in non-Hindi-speaking regions.

But what were the different historical and political contexts of these times? How did these movements (cropping in various parts of India) define the nation’s stance towards linguistic impositions and recognition of different identities? We shall (try to) explore all of these questions through the breadth of this essay. Throughout the article, we have also placed some brilliant books to better understand the language politics in India and the movements that defined it. Hop along!

Institutions and Movements Before Independence: Hindi as a National Tool?

Language shapes thought, and thought brings change. It’s natural, then, that language was a primary talking point in the Indian struggle for independence. The British colonial administration largely influenced pre-independence language policies, but as the independence movement grew, so did the need for a unifying national language.

Among the many languages spoken across India, Hindi was a strong candidate for this role. Why? Its widespread use in northern and central India made it an obvious choice for leaders like Mahatma Gandhi, who saw it as a way to unite India’s diverse linguistic communities and amplify the nationalist movement. The alternative—English—carried the baggage of colonial rule and was out of touch with the rural masses.

British policies had created a divide: English was the language of the elite, while the majority remained excluded. Hindi, by contrast, was more accessible, especially in rural India, and didn’t carry the same colonial connotations. However, things are seldom as simple as they appear from the outset.

Yes, Hindi was the lingua franca for many in the northern parts of India. But the larger parts of India—the south, northeast, and east—had their native languages, like Tamil, Telugu, Bengali, and Kannada, not to mention the host of tribal languages. These regions feared, not without reason, that the imposition of Hindi would marginalise their linguistic identities.

Recommended Reading: 15 Brilliant Indian Political Books for your TBR

The Formation of Institutions Like the Dakshina Bharat Hindi Prachar Sabha

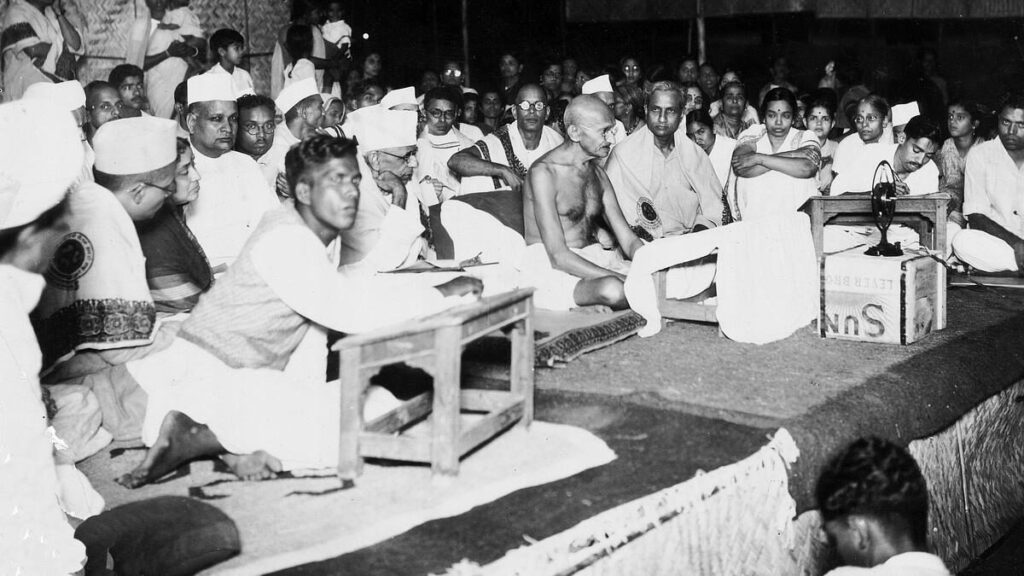

A key institution formed to promote Hindi in non-Hindi-speaking regions was the still-active Dakshina Bharat Hindi Prachar Sabha. Established in 1918 by Mahatma Gandhi, its primary objective was to spread Modern Standard Hindi in the southern parts of India, where resistance to Hindi was the highest. Gandhi envisioned Hindi as a bridge across India’s cultural and linguistic diversity. He even appointed his son, Devdas Gandhi, the first Pracharak (promoter)!

We need also a common language not in supersession of the vernaculars, but in addition to them.

– Mahatma Gandhi

The Sabha, headquartered in Madras (now Chennai), was part of the broader Hindi Prachar Movement, designed to spread Hindi through education, public campaigns, and examinations. Provincial branches sprang up across Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Kerala, and Andhra Pradesh. The organisation ran Hindi classes, held examinations, and conducted public awareness campaigns about the importance of Hindi as a tool for national unity. It also organised cultural programs, conferences, and Hindi Day celebrations.

By the 1930s, the Dakshina Bharat Hindi Prachar Sabha had become a well-established institution, with thousands of people enrolling in its Hindi courses each year.

Recommended Reading: Resistance Literature in India: Through the Years

The Justice Party and Self-Respect Movement’s Fight Against Hindi Imposition

The anti-Hindi imposition agitation of 1937-1940 in Tamil Nadu was one of the earliest organised efforts against the compulsory teaching of Hindi in non-Hindi-speaking regions. It started when C. Rajagopalachari, the Chief Minister of Madras under the Congress government, introduced a law making Hindi mandatory in schools. The decision was part of a broader effort to unify India through a common language, but it sparked intense backlash, particularly in Tamil Nadu.

When politics is disconnected from the masses, we get laws like this. The imposition of Hindi was seen not just as a linguistic mandate but also as a form of cultural dominance to marginalise the Tamil language and traditions. The anti-Hindi sentiment tapped into a broader anti-Brahmin movement, as Brahmins, though a small percentage of the population, held a disproportionate number of government and educational positions in the state. Many saw this imposition of Hindi as a further entrenchment of Brahminical dominance.

Periyar E.V. Ramasamy, leader of the Self-Respect Movement, was a key figure in mobilising the public. He, along with the Justice Party, led the protests, arguing that the compulsory teaching of Hindi was an insult to Tamil culture and an act of linguistic imperialism. The Justice Party, which represented non-Brahmin communities, framed the protests as both a defence of language and a part of the broader fight against caste oppression.

Periyar’s Self-Respect Movement, which promoted rationalism and anti-caste principles, found in the anti-Hindi agitation a powerful platform to challenge both the Congress party and Brahmin dominance. His slogan, “Tamil Nadu for Tamils”, targeted Hindi imposition as an external threat to Tamil identity.

Although traditionally a more moderate group, the Justice Party aligned with the Self-Respect Movement, uniting non-Brahmin communities in opposition. C.N. Annadurai, who would later rise to political acclaim, also amplified the movement. His oratory skills and sharp criticism of Hindi imposition helped mobilise the masses, later contributing to the rise of the Dravidian movement.

The agitation, which drew support from students, scholars, and women, saw large-scale protests, arrests, and heightened tensions. By 1940, the British government, wary of growing unrest, withdrew the order.

Yes, the immediate goal was achieved. But the movement also built the foundation for future agitations, culminating in the larger anti-Hindi movements in the 1960s.

Recommended Reading: Zen: Love and Resistance in a Politically Charged India

Language Conflicts and Resolutions in Post-Independence India

Indian governments and power, in general, have largely been Delhi-centric and Hindi-focused over the decades. But tone-deaf impositions carry their own repercussions, as we shall soon see.

The Official Languages Act of 1963 and the Initial Policy of Bilingualism

The language politics in post-independence India took a major turn with the Official Languages Act of 1963. This act was a response to the nearing expiration of the 15-year transition period specified in the Constitution for the use of English as an official language alongside Hindi. According to Article 343 of the Indian Constitution, Hindi was to be the official language of the Union, with English allowed for official purposes for the first 15 years (until 1965).

As this deadline approached, non-Hindi-speaking states, especially in the South, naturally started growing anxious about Hindi’s dominance. The Official Languages Act of 1963 attempted to address this by ensuring that English could continue to be used alongside Hindi, even beyond 1965. It stated that “notwithstanding the expiration of the period of fifteen years from the commencement of the Constitution, the English language may continue to be used for all official purposes.”

But the act used the word “may” instead of “shall,” which left room for ambiguity and continued the protests. While this act was a stopgap, it was insufficient to quell fears of Hindi imposition.

The Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), a political party with deep roots in the Dravidian movement, rose as a political force in these years. They sought to protect Tamil culture from what they perceived as an attempt to impose Hindi on the Southern states. The party’s founder, C. N. Annadurai, vehemently opposed the Act based on the fear that Hindi imposition would marginalise non-Hindi speakers and reduce their employment opportunities, especially in government sectors.

The 1965 Agitations in Tamil Nadu: Key Events, Political Responses, and Outcomes

1965 saw one of the largest language protests in Indian history, another turning point in language politics in India, predominantly in Tamil Nadu (then Madras State), triggered by the possibility of Hindi becoming the sole official language. The situation intensified after Jawaharlal Nehru died in 1964. Many had started fearing by that time that his assurances for the continued use of English would no longer hold.

However, the immediate cause of the protests was something else. In 1965, the state government introduced the Three-Language Formula—mandating the study of Hindi, English, and Tamil.

The agitations, led primarily by the DMK under C. N. Annadurai, began in January 1965. On January 25, 1965, protests erupted across Tamil Nadu, with students at the forefront. Violence soon erupted, and in Madurai, a fierce clash between Congress workers and student protestors escalated into full-blown riots.

In the following days, widespread violence spread across the state, with burnt buses and damaged public property. Self-immolations were rampant, most notably that of Chinnasamy from Tiruchirappalli, a DMK member, who came to symbolise the anti-Hindi movement.

In response, the government dispatched paramilitary forces to quell the unrest. Official estimates report roughly 70 fatalities and the arrest of thousands, including prominent figures like Periyar and Annadurai. Eventually, the central government, under Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri, was forced to intervene.

If we had to accept the principle of numerical superiority, the choice for our national bird would have been the common crow, not the peacock.

– C. N. Annadurai

Shastri assured that English would continue to be used indefinitely alongside Hindi, a significant concession from their earlier position, to calm the unrest. This decision finally acknowledged the fact that imposing Hindi across a multilingual and diverse nation like India would be politically untenable.

The Amendments to the Official Languages Act in 1967

In 1967, to formalise the government’s promise, the Official Languages Act was amended. The key change was that English would continue indefinitely as an official language, and therefore, Hindi would not be the sole language of governance.

The act now clearly stated that “English shall continue to be used” for official purposes of the Union and communication between the Union and non-Hindi-speaking states. This amendment effectively ensured the indefinite use of both Hindi and English as the languages for official communication in India, avoiding a single-language imposition and removing any ambiguity left by the 1963 Act.

This amendment soothed the concerns of non-Hindi-speaking states, especially in the South. It curbed fears of Hindi overshadowing regional tongues, reinforcing the principle of bilingualism, which remains relevant to India’s language policy today.

Regional Identity and Language Politics in India: The Cultural Impact of Anti-Hindi Protests

The anti-Hindi movements in India have had lasting impacts throughout the country, shaping regional political identities and preserving linguistic diversity over the decades.

The Impact on Tamil Nadu’s Political Landscape and the Rise of Dravidian Parties

The language movements in Tamil Nadu, particularly the 1965 anti-Hindi agitations, were pivotal in the language politics in India, marking the beginning of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam’s political dominance. The party, founded in 1949, initially campaigned for Tamil Nadu’s secession from the Indian Union, advocating for the formation of a separate Dravidian state known as “Dravida Nadu.”

Although the secessionist agenda eventually faded, the party’s anti-Hindi stance continued to define its identity. The DMK used this anti-Hindi sentiment to galvanise support, leading to its victory in the 1967 elections and displacing the Indian National Congress from power.

Since then, the political stage in Tamil Nadu has been dominated by the DMK and its rival, the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK). Both grew out of the Dravidian movement, resisting what they saw as the northern cultural hegemony.

Changes in Public Policy and Administrative Languages

The anti-Hindi agitations led to many changes in language policy both in Tamil Nadu and at the national level. We’ve already read about the 1967 amendments, which indefinitely extended the use of English alongside Hindi as the official language of India. In Tamil Nadu, Tamil became the primary language of administration and education. Successive governments maintained the state’s linguistic autonomy.

The state also boycotted mandatory Hindi education programs introduced by the central government. But this struggle for linguistic autonomy wasn’t limited to the state.

The Role of Language in Shaping Regional Political Identities

While Tamil Nadu is the most prominent example, many other Indian states also saw anti-Hindi movements, each with their regional nuances. We look at some examples below:

West Bengal

In West Bengal, anti-Hindi sentiment has simmered for decades. The rise of nationalist politics from the Hindi-speaking heartland, particularly through the BJP and RSS, has added to these tensions. Of late, protests have flared against Hindi’s prevalence in public arenas like metro stations and banks. Activist groups like Amra Bangali and Bangla Pokkho have led demonstrations against the imposition of Hindi, advocating for the use of Bengali in official and public communications.

However, the conflict has also spread into Darjeeling, where imposing Bengali in schools triggered protests from the Nepali-speaking Gorkha community, resulting in widespread unrest in 2017 and demands for a separate land.

Karnataka

In Karnataka, language politics has long centred around protecting Kannada while resisting the perceived imposition of Hindi. It started with the States Reorganisation Act of 1956, which united Kannada-speaking regions into the state.

By the 1980s, the Gokak Agitation became a defining moment when activists, supported by figures like Rajkumar, successfully demanded Kannada be made the primary language in schools. Even today, the resistance continues through movements like #NammaMetroHindiBeda (We don’t want Hindi in our metro) and protests against Hindi Divas to ensure Kannada continues to play a central role in the state’s identity.

Assam

Language politics in India reached a boiling point in Assam in the early 1960s with the Bengali Language Movement in the Barak Valley. The Assam government, under Chief Minister Bimala Prasad Chaliha, decided that Assamese would be the state’s only official language.

But for the predominantly Bengali-speaking population in Barak Valley, this felt like their identity was being sidelined. The tipping point came on May 19, 1961, when peaceful protestors gathered at Silchar railway station were tragically fired upon by the police, leading to the deaths of 11 people, including 16-year-old Kamala Bhattacharya, the first female martyr of a language movement in India. This heartbreaking incident sparked a wave of public outcry, forcing the government to amend its policy.

As a result, Bengali was granted official status in the Barak Valley through the Assam Official Language (Amendment) Act, 1961. While this was a win for the Bengali community, it also deepened the Assamese-Bengali divide, a rift that continues to shape the socio-political fabric of the state today.

Punjab

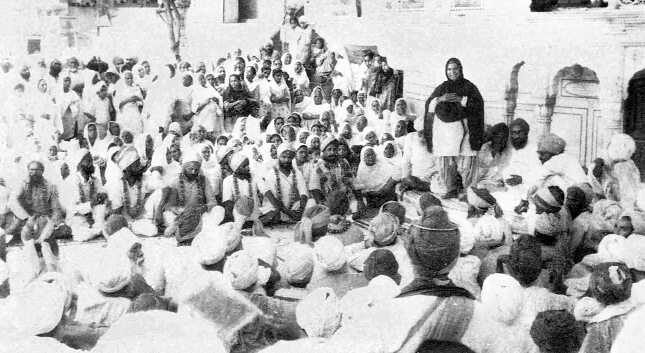

The Punjabi Suba Movement was a cultural and political struggle that shaped modern Punjab. Led by Master Tara Singh and the Shiromani Akali Dal from 1948, the movement aimed to create a Punjabi-speaking state, which the Sikhs saw as crucial for preserving their religious and cultural identity post-Partition.

On one side, the Sikh community fought for Punjabi, while Hindi-speaking Hindus feared being sidelined. This divide deepened after the 1951 Census when many Hindus chose Hindi as their mother tongue. Years of protests led to the Punjab Reorganisation Act of 1966, which split the state into Punjab for Punjabi speakers and Haryana for Hindi speakers and made Chandigarh a union territory. While it felt like a win for the Akali Dal, it also deepened the religious and linguistic rifts.

Recommended Reading: Indira Gandhi, Bibliophiles and Love: Once Upon a Curfew

To Conclude…

Linguistic diversity is central to India’s pluralistic identity. This diversity preserves cultural heritage while strengthening democracy by enabling citizens to communicate with the state in their native languages. The anti-Hindi protests highlight the challenges of pushing for a monolingual policy in a nation teeming with over 1,600 languages.

The anti-Hindi movements and the subsequent language politics in India, particularly in Tamil Nadu, have had significant socio-political impacts on India’s language policy. These movements have successfully influenced the government to continue using English alongside Hindi as an official language, preventing nationwide discord and maintaining linguistic self-determination.

Amid rising linguistic nationalism in India under the current government, these post-independence language movements are a reminder of the importance of this country’s inherited linguistic diversity.