Published originally in Malyalam, Valli is a climate fiction, told through the point of view various characters. It’s translated by Jayasree Kalathil, the joint winner of JCB 2020, along with S. Hareesh (Moustache).

Valli and the mountains

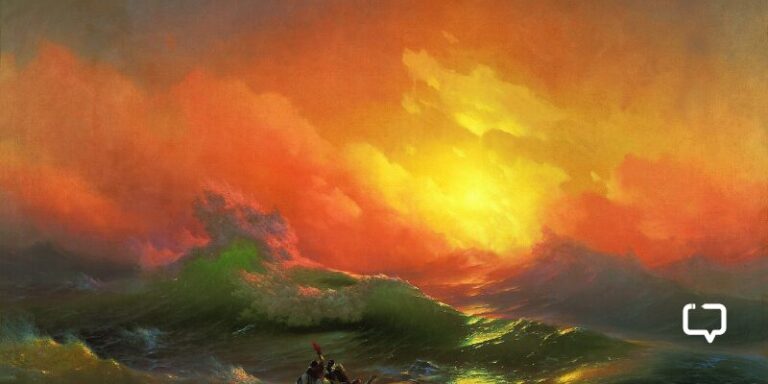

Do you remember these phrases? ‘The Mountains are calling/The mountains are calling and I must go.’ Valli is what happens after the tourist has left the mountains to go back to the drudgery of their everyday corporate life, having bitten into an artificial, curated experience of what they call a ‘pahadi life’.

Valli is what happens after the notorious trifecta of corrupt politicians, land sharks and bribe-hungry bureaucrats join together to embezzle and take what rightfully belongs to the people. Valli is what happens when mankind progresses and develops because both these words and phenomena, ‘progress’ and ‘development’ come at a huge cost to nature, especially species that aren’t human.

Tomy writes:

Ever so slowly, the forest cleared, and the porcupine, the sloth bear, the wild boar, the pangolin, the civet, the anteater, the snake, the mongoose, the hare, the peacock, the muntjac and thousands of other creatures withdrew deeper and deeper into the jungle.

The story starts in 1970s, when Sara and Thommichan, two teachers, elope to Wayanad in hope of finding peace and a life of love. Spanning four generations, Valli is partially the story of land and partially an epistolary experience since Susan, daughter of the aforementioned teacher couple is writing letters to her daughter Tessa.

It shines in the passages where Tomy talks about land, adivasis, their struggles and what nature offered to the region of Northern Kerala and what the mankind has brought it to. Tomy has set the story in the majestic land of Wayanad, mentioned here as Bayalnad (It would become Wayanad later, but its old name is ‘Bayalnad’ – land of the paddy fields. A land marked by steep hills, sheer cliffs, vast valleys and treacherous rock formations.)

Land, people, and the question of ownership

Valli makes for a case against unchecked development and tourism. The constant commercialisation and plunder of land. Tomy, who is from the region, is able to make this loss personal. She mourns the land and how it’s been forced to not only change but metamorphose. Read on:

Eventually, the scent of cashews faded, and in its place, the rousing fragrance of coffee wafted across the land. Ripe coffee berries fell like coral beads across the leaf-littered hillsides, heralding another time of plenty. More things came up the hills – rubber, black pepper, ginger – and through it all, paddy fields in shades of green and gold lay fecund in the valleys, ushering in harvest seasons smelling of kaima rice.

Tomy highlights the plight of adivasis and the practice of landowning and sharecropping. Rich landowning farmers (jemmis) take Adivasi people on lease as labourers and make them work on their lands. It’s called ‘vallippani’ – labouring in return for valli, a share in the crop. It’s a sort of bonded labour. Even though slavery has been abolished, and there are laws about minimum wages, the practice of ‘vallippani’ rages on. I

f someone tries to rebel or revolt, they are dealt with brute force. Tomy writes:

‘He knows all about what this land has had to suffer, how the poor end up working for the jenmis for a whole year, and for what? A piece of coarse cloth for the Valliyoorkaavu festival, seven and a half seers of rice, five rupees as bond money, and a couple of meals a year! The whole family has to work for a daily wage of two seers of rice. And if they break the bond and go and work elsewhere, they’ll have to suffer what happened to Mooppan’s son, Mallan.’

A little too faithful to the life?

In a way, Valli is a spiritual sister to S. Harish’s JCB winning book Moustache. Moustache too highlighted the plight of Pulaya Dalit community in Kuttanand of Kerala. Vavachan, a Dalit man, one day decides to keep a moustache, riling up the upper castes.

Valli doesn’t delve into magical realism but brings forth the harsh reality to the pages. The only grouse I have is that it mirrors life a bit too faithfully. Many passages, like life in general, are mundane where the story seems to have gotten stagnant.

Best quotes about nature

Sometime much later, somehow, as the hills began to withdraw into the earth and the paddy fields began to disappear, far-hill and near-hill became strangers. But Kalluvayal remains, even today, its rivers thin, its forests bald. A land where countless secrets sleep in the vast stone structures and deep caves left behind by Stone Age humans.