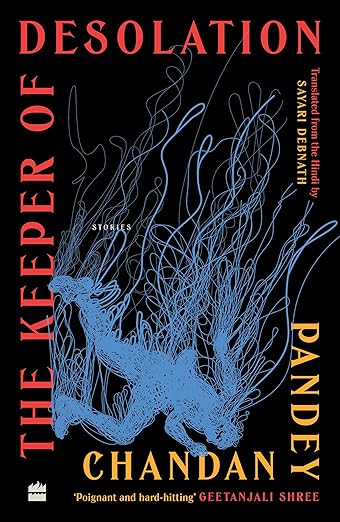

The nine stories of Chandan Pandey and Sayari Debnath’s The Keeper of Desolation are stories coming together, translated hindi stories that show us a different India; one we may not necessarily meet every day. Of the men whom we may only read about in the newspapers

Not the newspaper that you open on an app; but the one that marked a new morning each day, dropped at your door with clock-work precision. The one your father and grandmother would struggle to read first or else the pages would get all crumpled up.

Because that was the newspaper that carried the stories (misfortunes?) of the men that populate the world created by Pandey and Debnath in this translated Hindi book. These are the men that live in India, not in ‘new India’, mind you. For Pandey has written only about men and the ones that you would find in the queues of a bank (if you still visit one) trying to get a (tractor/home/education) loan sanctioned or in a post office trying to reap the benefits of some two-penny investment scheme.

Sayari Debnath upholds the essence of these translated hindi stories

Sayari Debnath’s translation is superbly invisible. It’s ironic that more ‘untranslated’ a translation reads, the better it’s ranked. As someone who knows both Hindi and English, there were a few sentences that made me wonder: what would they be in the original text? But these sentences were few and far in between. That’s also a win for a translator. Not to let the bilingual reader chewing upon the backstory of the translated word. The poems, it is said, are difficult to translate. Debnath shines here too:

Aankhon mein khulta hua aasmaan

ya phir titliyon ka sanghralay

ya phir gussail chintiyaan apne aap ko paani par

dhakel rahi hain.

The translation reads:

In the eyes is the sky unfurling

or a museum of butterflies

or a string of furious ants dragging

themselves over water.

The stories urban India misses

The characters of The Keeper of Desolation‘s translated hindi stories often come in the vernacular variety, on the third or fifth page, under an obscure heading of ‘local news’ or ‘city news’.

They get arrested on suspicion of being a terrorist, of nicking a gold ring off a cop wife, who lie to their girlfriends and don’t talk to their wives, who die by falling into septic tanks.

They write letters to politicians to ease off their loans. They are murdered because they didn’t offer a seat in a cramped bogey of a train (that plies from a junction to another in the old India) to another man.

These are the men who murder a man because the money they had received after selling their land has run out. These are the men who kill and maim just because they can.

These are the men who hide their poems from their boss. These are the men who think about chopping off their leg to get insurance benefit.

They will always be lurking on the third page or the fifth or the seventh one. Not on your phone. Never on your phone.

Storytelling styles that stand out

Pandey’s stories often start with a hook, only to cast it off like a much-holed vest and dive into the murky of the backstage.

So in the very beginning of a story called ‘Forgetting’, you find a man thought-shaming another for not plucking flowers for his sweetheart, thinking all this while that if he were in his place, he would have scaled the damn tree. It is only when you start to read, you get to know that he had been responsible for pushing his brother into a trap of ambition and earning, currency and coins. He and the entire family saddled him with the weight of their own failure.

The story moves on a precarious zone between the real and the imagined, skirting the very edge of (magical?) realism. The apathy and emotional violence drips from these lines:

‘At 25, he had already been inactive for seven or eight years, and there was no knowing how long he would continue this way. Even when he was younger, we had to cup our hands around his ears and speak loudly into them for him to hear us. On top of this, he was totally blind too… Alone in his shanty, whenever Gulshan needs anything, he simply calls out loudly for me or our mother or Shalu. Whoever is free goes to him, but if they’re not, he might have a long wait. In the meantime, the smile never leaves his face.’

A touch of dark humour in this collection of translated Hindi stories

In the world our characters inhabit, misogyny is the norm, and Pandey has portrayed them just as they are in this collection of translated Hindi stories. ‘The Junction’ starts with a rumour of the narrator’s love affair with a bureaucrat goes off track. The narrator here is uncomfortable to see a woman as a high-ranking officer, someone in a position of authority.

His discomfort and misogyny are reflected in these lines:

‘The chair was occupied by a beautiful lady-this rattled my confidence for a moment, but quickly became a source of relief. Suddenly, a thought popped up in my mind. Why not assign all fearsome and death-dealing positions to beautiful and refined women?’

Pandey’s humour, when it comes, comes dressed up dark. These lines are so sharp, you might cut your irises upon paper. Have a look:

‘He declared that he only accepted the greetings of those who had at least a BA degree. He got along especially well with those who had double MA degrees or a PhD.’

‘When I visited him, I found him writing two articles, one with each hand. With his left hand he was writing about the necessity of land grabbing, and with the other one, a condemnation of the act. He even finished both articles at the same time.’

‘I am known for the corporal punishment I mete out. On the days I remove my ring from my right hand and relocate it to my left, no one, including me, can predict which classroom will be at the receiving end of my infamous wrath.’

This black humour, tinged with sadness, shines in ‘The Mathematics of Necessity’ where the protagonist writes a letter to PM of India to introduce a tweak in the formula of compound interest on a tractor loan.

As the story progresses, it dives between humour and pathos, and ultimately bruises its shins on the threshold of yawning poverty. The protagonist, a farmer but pushed into teaching, has taken a loan without asking for the rates of interest. And he also needs a trolley if he wants to rent out that tractor!

The story swells towards the end when the reader comes to know that the letter-writer has also CC’ed God and President of USA. He is also rueful for addressing the latter second in order after God. He claims that the president, after all, is well aware of who will emerge the winner.

Reality is sad and violent; and we live in denial

The narrator here dreams about inflicting violence upon his students. He wants ‘to pick up a student, turn him upside down, and bang his head on a desk. I could even kill someone if I wanted to, and no one would dare question me.’ At the same time, his mind is swirling with such philosophical musings: ‘Numbers do not lie. And they are not traitors. I would even say that numbers are just like pets. Mathematics can neither enjoy the freedoms of physics nor be misinterpreted like history. Yet, it is mathematics that has been responsible for the fall of civilizations-not history.’

The eponymous story of this collection of translated Hindi stories – ‘The Keeper of Desolation’ – is a shiny mirror where sarcasm draped in a diaphanous gown of tears shines sadly.

A cop wife’s ring goes missing. The poor, who always pay the price, are rounded up. They, of course, are blamed with the theft. I would urge you to read this original or the translation of this Hindi book just because Pandey has written this gem. Have a look at this sad sarcasm: ‘Police stations across the town reported that some forty thieves had been taken into custody. The man who pumped air into punctured bicycle tyres, the porter who worked at the vegetable market, and the man who sold eggs were all accused of the crime.’

Each piece in this collection of translated Hindi stories is something that you might have read in a newspaper. If you compare these stories to the shiny peacock of new India, it would look like the majestic bird has sprouted the wings of a crow. This shiny new India, sadly, sits as uselessly upon the stories of Pandey like a peacock’s plume upon the diseased head of a dying crow.

Pick up the newspaper.