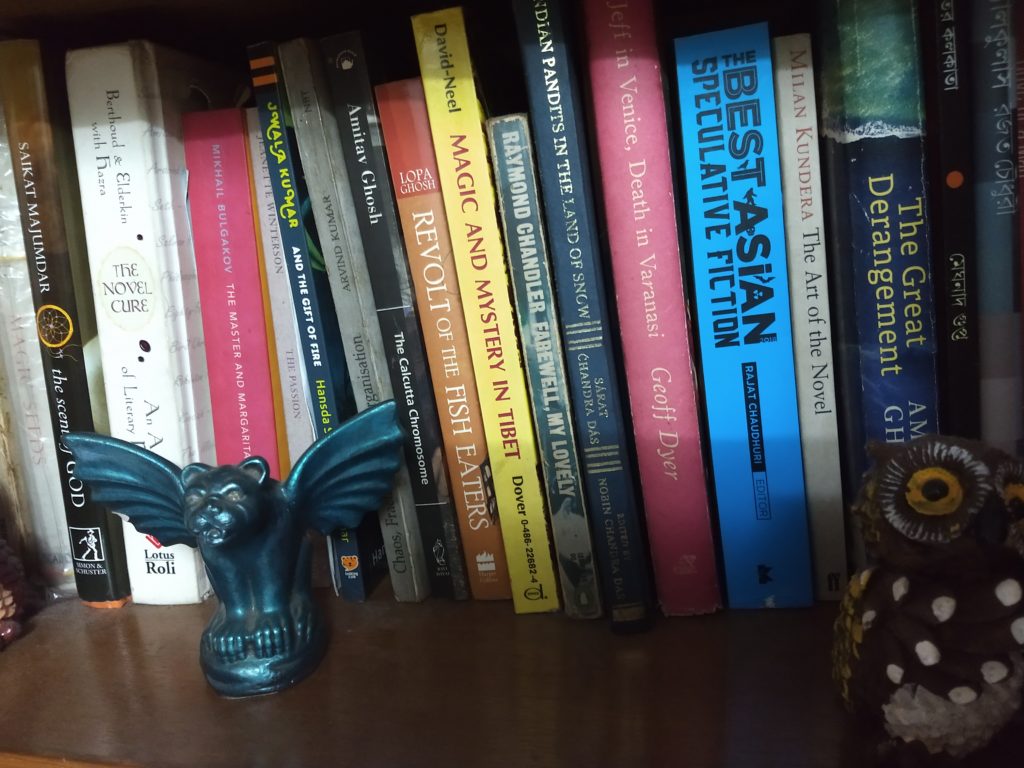

Rajat Chaudhuri is an an environment activist, author, and translator. He has published six books in two languages including fiction and translation. He selected and edited The Best Asian Speculative Fiction (2018) collection of stories. Chaudhuri’s climate change novel The Butterfly Effect (2018) is listed as one of `Fifty Must-Read Eco-disasters in Fiction’ by Book Riot (US).

About The Butterfly Effect: “From utopian communities of Asia to the prison camps of Pyongyang and from the gene labs of Europe to the violent streets of Darkland – riven by civil war, infested by genetically engineered fighters – this time-travelling novel crosses continents, weaving mystery, adventure and romance, gradually fixing its gaze on the sway of the unpredictable over our lives.”

Excerpts from an exclusive interview with him:

Was there a particular phase in your life that influenced your decision to be a consumer rights activist and a writer later?

Rajat Chaudhuri: I had been an environment and climate activist, working with a consumer group. You know activists don’t really retire, if they are dedicated, so my environment and climate change work continued in different formats.

I studied economics at college and university and when you are neck deep in that subject you begin to think what lies beyond the free market-led growth paradigm of economics and that’s when sustainability and environment come into the picture. That’s how I got interested in this stuff.

Writing, all kinds of writing, was always in the picture but at one point I felt that the experience I had been gathering could find another channel in literary expression.

I still believe that but now, to take my novel The Butterfly Effect as an example, I feel I am able to better engage my activist self with my fiction.

How much do you think the digital space has affected the conscience of people in India, in reference to writing about climatic change?

Rajat Chaudhuri: I assume you mean climate change and not climactic events and changes though these can have overlaps. Either way the digital space is important as it has fostered democratisation of opinion. Naturally it has also led to circulation of extreme views.

The internet and social media because of the way it’s organised, the way algorithms are designed, tends to reward nutcases. Belligerence, polemics, highly opinionated views tend to get more traction as do individuals who, honestly or otherwise, are ready to bare their soul before the machine.

You cannot live with the extremists nor can you, especially if you are a loner by nature, offer your life on a plate to the hungry algorithms of social media. But there is also a middle ground through which well meaning people can interact, share, discuss and debate in a civilised manner about the major issues affecting the planet of which climate change is one of the most important.

You’ve created a dystopian world called Darkland in one of the stories, coupled with a beautifully realistic description of the “decrepit mass of humanity”. Is this place inspired from a real life location?

Do you also like to read fantasy? What are some of your favourite fantasy/dystopian books, or sources of inspiration, if any?

Rajat Chaudhuri: Darkland is one of the settings for my most recent novel The Butterfly Effect which begins in the recent past and takes us to a possible future where climate change disasters have become common and a pandemic is sweeping across the population of Asia.

It has many parallels with the present pandemic. In the book, the countries and regions most affected by the pandemic are collectively called Darkland. In general it is not inspired by any particular location but at the centre of Darkland is a city without name and that is an imagined Calcutta of the future when the sea levels have risen enough to drown parts of it and the government of Darkland is headquartered there.

I read across genres. I’m reading a lot of climate change fiction (cli-fi) over the last two or three years and some of that is dystopian. But there are stories of hope too or just stories of the present where climate change through its various manifestations is an increasingly bigger threat.

Some of my favourites from the past are of course the obvious ones:

Brave New World

1984

Zamyatin’s We

I have also enjoyed:

Doris Lessing’s Mara and Dann

Liz Jensen’s The Rapture

Barbara Kingsolver’s Flight Behavior

Amitav Ghosh’s Gun Island

Cormac Mccarthy’s The Road

Marcel Theroux’s Far North

The character of Detective Kar was also present in one of your earlier novels, Hotel Calcutta. Do you have a special attachment to this particular character?

How is the Detective Kar of this novel different from the previous? How does a writer approach continuity when writing about characters across books?

Rajat Chaudhuri: Oh yes, absolutely. In fact he first appeared in my Bengali fiction in a story about the kidnap of a novelist in Calcutta. Then in Hotel Calcutta, where everyone is turning into a kleptomaniac. Kar binds together whatever is absurd and irrational about the storyworld and the plot through his rational private eye approach but he can be illogical too.

The Butterfly Effect has three timelines—past, present and future. In the timeline of the present detective Kar is not very different from how we see him in Hotel Calcutta or in my Bengali fiction.

Maybe just a little older, he is losing his hair too quickly and this alopecia worries him so much that it’s coming in the way of his investigative work giving rise to comic scenes and situations.

Otherwise he is quite the same hard-drinking, slightly debauch private eye working out of that same office in Calcutta’s Crooked Lane. And he still carries the Russian Makarov pistol and visits the Chhota Bristol bar behind Metro cinema.

In the future timeline of the novel he changes a lot and I can’t tell you how without giving away the plot!

To maintain continuity I use character bios detailing everything from eye colour to graduation results.

Rajat Chaudhuri

You have received several grants from various national and international organisations, in addition to the multiple fellowships – how important you think such titles are in the contemporary socio-economic scenario?

Rajat Chaudhuri: Fellowships, residencies and writing grants are all important for an author but that doesn’t mean someone without any of these is at a disadvantage. It depends on the person, her surroundings, what s/he is comfortable with.

My fellowships have helped both in terms of exposure and quiet time for writing. I have made good friends, lifelong associations and the books that I have worked in at residencies in India and abroad have been consequently published.

Because writing doesn’t really pay the bills for most writers, writing grants and fellowships which come with a good honorarium are always good news.

How much do you think literature can warn people about the environmental dystopia and how can readers participate?

Rajat Chaudhuri: Stories can help people imagine (and forewarn them about in some cases) possible worlds, dystopic or otherwise. It can also help us connect with these possible realities and often motivate us to create better futures as imagination is the first step of creation.

Again, the world building of science fiction or let us call it speculative fiction can provide us with a menu of possibilities for future societies and help us design transition pathways to these better worlds. Impact-wise, dystopia is not all negative as despair can also give us hope and motivate us to take action. Keira Hambrick points out that readers know how to decouple the dystopia element and respond to the call-to-action of a book.

There is this whole new world of solarpunk stories (I am co-editing an anthology which will come out early next year) which portray positive futures not necessarily via a dystopian interlude but straight from the present. That’s what we need more of.

Of course, literature on its own cannot change the world and we require concerted efforts from policy makers, scientists, academia, civil society, governments and others. Many of these change-makers are also readers.

It’s always easier to experiment with change, create examples, models, solutions at the niche level which can later influence bigger and widespread transformation. So to return to your question, we need more readers groups online or offline to discuss, review, debate this kind of writing and then engage with civil society groups that are involved in sustainable development work.

What are some of the ideas and concepts that you think got lost in the narration, but you want to highlight to your readers?

Rajat Chaudhuri: The urge to edify (the reader) and change the world is akin to the sexual urge, it can blind you to the risks and kill your story. Many writers fall in that trap, giving us immensely boring work. Well, literary fiction can also bore but in a different way. With lit fic you just fall asleep with the book on your lap while in the former case you just want to run away and grab a drink.

I think it’s best to leave the task of judgment to the reader and reviewer. Storytelling has its own rules and you can really not transform it into an activist tract with action points and so on.

Having said that I must draw your attention to counterfactual examples. Kim Stanley Robinson’s novels, say Pacific Edge, manages to pack in a lot at the level of ideas rather ideas for transition to a sustainable future which you won’t find in many books.

Amitav Ghosh’s Gun Island beautifully conveys the omnipresent, hyper-object like quality of climate change through a stories set in the present and the past.

It can be done and authors are doing it with different levels of success. In my novel I would have loved to make the connections between our actions and the climate disasters more prominent but that would be deviating too much from the story which is about a specific ecological disaster.

So often, there is this tension between the story and this bunch of ideas or political messaging related to climate change and ecological disaster which you think is necessary to convey. This tension, I feel, is birthing a completely new kind of writing.

How much you think Indian Literature has contributed to this understanding?

Rajat Chaudhuri: Contemporary writers from this country, barring Amitav Ghosh, haven’t explored climate fiction that much. But ecological and environmental disaster themes have always been part of Indian writing.

Talking of Indian English fiction, I can immediately think of Indra Sinha’s Animal’s People about the Bhopal gas disaster, Prayag Akbar’s Leila and Sarnath Banerjee’s graphic novel All Quiet in Vikaspuri.

These can be labeled ecological or ecofiction with dystopian elements in some. In the realm of short stories, many are writing or have written cli-fi, Kanishk Tharoor being one of them. Children are luckier as there are good stories with environmental themes getting published for example Bijal Vachharajani’s A Cloud Called Bhura.

Water and its interconnectedness with lives is well woven into the fabric of Malayalam, Bengali and other Indian literatures. In Bengali we have the great river novels – Titas Ekti Nadir Naam (Adwaita Mallabarman ), Teesta Parer Brityanto (Debesh Roy), Ganga (Samaresh Basu), Padma Nadir Majhi (Manik Bandopadhyay), Ichhamati (Bibhutibhusan Bandopadhyay) and Mahanadi (Anita Agnihotri) but they are not all talking about water conservation per se.

The post colonial writer looks at her material through a different lens which is why issues like climate change or sustainability resolve slightly differently in our fiction. However, ecofiction and post-colonial fiction are coming together through issues like climate justice and one good example of that is to be found in Amitav Ghosh’s most recent climate novel.