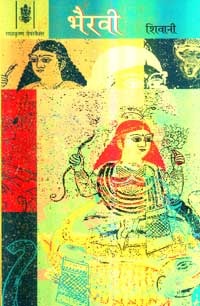

Bhairavi by Shivani is about contradictions – the traditional and the modern, the contemporary and the past, and even the doer and the observer. A young woman appears in a settlement of Aghoris, the Shaivite sadhus who practice death rituals. The leader of the Aghoris, Maya Didi, calls her Bhairavi, and holds her in her thrall. How did she get here?

We encourage you to buy books from a local bookstore. If that is not possible, please use the links on the page and support us. Thank you.

As the story unfolds, we learn what led her here. We learn of her mother, Rajeswari, who makes an unfortunate choice of friend, and is married off to an elderly gentleman who soon leaves her a large house. Rajeswari attempts to make her place in the modern world by training to be a teacher and allowing education into her life, but cannot let go of echoes of her past. She demands that her young and beautiful daughter Chandan maintain rules of caste and observe Hindu rituals, until one day, the beautiful and mysterious Sonia and Rukmini step into her life, to ask if they may make Chandan their daughter-in-law.

But all is not well in Chandan’s marital home, and there is a palpable, uneasy tension between the traditions she was taught to observe in her mother’s house, and the ‘modernity’ of her smoking, jeans-wearing sister-in-law, and the mother-in-law who can barely keep her under her control. Chandan’s new husband, Vikram is enthralled by her beauty and her good nature, and her sister-in-law Sonia is only to eager to be her friend. Yet things do not go quite as planned, and Chandan ends up with the Aghoris, with nothing more than the clothes on her back.

In Shivani’s story, the past doesn’t belong to a distant universe, it is here, and now, waiting to creep up on the present. It is in Chandan’s upbringing, in the strict caste rules of Pahadi Brahmins under which she is raised, and the strict observances of Hindu rituals. For her mother-in-law, Rukmini, the bright-eyed, new daughter-in-law represents the past she wishes she could go back to, one where these traditions are alive and well. For Chandan’s mother, Rajeshwari, the choice to raise Chandan in a traditional, timeless way stems from the one youthful mistake she made. The past is a prison, from which it is impossible to escape – not for Rajeshwari, not for her daughter Chandan.

Shivani uses gothic imagery to great effect, in the most unexpected places. Sonia appears in Rajeshwari’s little world, just as she begins to think about Chandan’s marriage, with her hair that looks like a snake and an outfit that leads Rajeshwari to mistake her for a little boy. She contrasts Chandan’s lovely, fair-skinned, naïve countenance with the terrifying, bare-breasted, chillum-smoking Aghori, Maya Didi, just as she contrasts Rajeshwari’s strict upbringing with that of colourful, indulgent courtesan whose daughter she is friends with. The imagery – the snakes, the forests, the Aghori rituals, convey just how out of place Chandan is in each world. The beautiful Chandan is too lovely to be left unmarried in her mother’s home in the hills, too naïve to fit in with her city-dwelling in-laws, and too sheltered all her life to truly fit in with the Aghoris.

But most of all, Shivani’s powerful imagery in Bhairavi – the mansion in the hills, the large house in the cities, the train ride, conveys just how trapped Chandan is, wherever she might be. As a young girl in the hills, her mother and her traditional observances limit how much freedom she can be granted. As a young bride, she is confined by her new husband and his family. Shivani uses a train compartment to convey this claustrophobia with great effect – and to tell us just how easy it is to escape the confines of modern life and escape into the past.

And the past – in this case, the morbid, chillum-smoking, death-ritual practising Aghoris – does represent a kind of freedom for Chandan. The Aghoris famously abhor all fear of death, and participate in rituals involving corpses to express this conquest of their fear. In Shivani’s novel, they represent an escape from the prison that is society and its expectations. They also represent a point of no return – the price of freedom with the Aghoris, it turns out, is that you can never go back to your old prison.

Priyanka Sarkar’s translation of Bhairavi is riveting, and the claustrophobia of Chandan’s life is palpable. The characters are of a certain upper class and upper caste sub-set of society, and Shivani captures just how confining caste rules and observances can be for women. I did find myself wondering why the story rambled so, but it comes together remarkably in the denouement. And yes, this is very much a story about women, told through multiple, distinctly female gazes. It’s a powerful read.

Favourite lines:

‘It is not difficult to run away from your husband’s house, Bhairavi,’ Maya Didi had once said to her swaying in her intoxication. ‘What is difficult is returning there. The door you had opened and jumped out of, will you be able to return to it?’