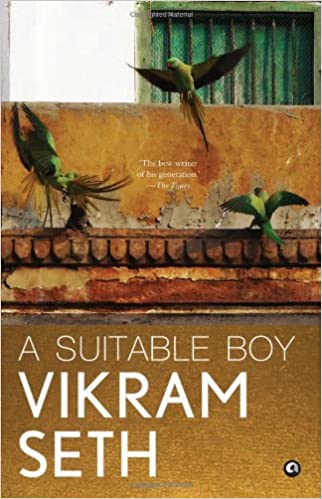

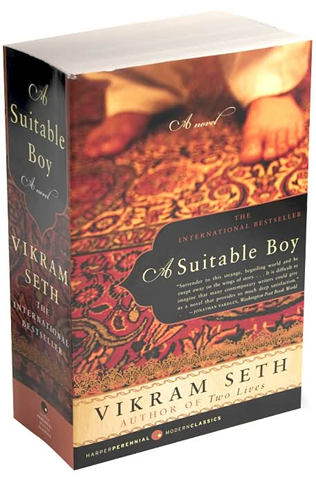

Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy is charming if a somewhat rambling tale of love and marriage. At over 1300 pages and 591,552 words, A Suitable Boy isn’t so much a novel with a plot, as much as a series of intersecting, meandering accounts of people’s lives in the social and political context of 1950s India.

Four years after independence, Mrs Rupa Mehra decides that her daughter Lata “will marry a boy I choose.” The Mehras live in the fictional town of Brahmpur in Purva Pradesh, a city somewhere on the banks of the Ganga.

Their quest for this suitable boy crosses paths with the lives of Mr Mahesh Kapoor, the Minister of Revenue of Purva Pradesh, his sons, Pran and Maan, as well as the erstwhile Nawab of Baitar, the courtesan Saeeda Bai and many others, as Lata is courted by not one, but three men – the eminently suitable and loving (but Muslim) Kabir Durrani, the suave poet Amit Chatterji and the industrious, stolid, Haresh Khanna.

Along the way, they must address the aftermath of Partition and growing communal tensions, the changes that the new Constitution will bring and even their own identities as Indians.

The Indian identity

If there is a theme to A Suitable Boy, it is the question of what it means to be Indian. Lata and her siblings are educated in convent schools and speak to one another in English and read P.G. Wodehouse when they have a bad day. Lata’s older brother Arun works with the British firm of Bentsen & Pryce and does everything to be English in his way of life – cocktail parties with his wife Meenakshi, crosswords, and no efforts spared to impress his English bosses. Other characters, like Oxford-educated poet Amit Chatterji, are more comfortable with writing and speaking English than their mother tongues, and more at home with Wordsworth and formal dinners, than with getting their hands dirty in a leather factory. The upper-caste, upper-class characters might be traditional enough to observe Hindu festivals and search only for a suitable boy in their own caste but are perhaps more English in their thoughts and in their education than the vast majority of Indians.

Other characters cling to their Indianness. The courtesan Saeeda Bai still performs at mehfils, and hosts lovers, like the ghazal aficionado Maan Kapoor, at her residence. Wealthy landlords and princes, such as the Nawab of Baitar, can still patronise musicians and the arts. Many within the Mehras’ social circle, such as Mr Mahesh Kapoor’s family, are much more comfortable in Hindi or Urdu than in English. Meanwhile, a new generation of Indians, who speak English with Indian accents, are beginning to take over the industry and public lives in India.

Socio-political contours

Seth weaves this question of what it means to be Indian into the social and political setting of his book as well. Mahesh Kapoor’s pet project, the Zamindari Abolition Bill, is part of a series of land reforms that new governments brought about in the 1950s, while the Nawab of Baitar’s writ petition is only one of many challenges to these laws in the early years of constitutional litigation.

The judges of the High Courts, Lata’s brother’s father-in-law Justice Chatterji among them, must now grapple with the new constitution and its writ petitions before Public Interest Litigation was commonplace. This is an India that is still coming to terms with elections, with being in control of its political destiny, with the meaning of secularism and – tragically – communal riots over sites of religious worship.

An independent India, and the newly independent Indians, must now confront these questions head-on. And confront, they do, in public and in private. Seth’s characters navigate their personal relationships through the lens of these public events. Friendships between Hindus and Muslims, the upper caste and lower caste, politicians and the soon-to-be-displaced, these are lines that form between people and sometimes despite their best efforts.

Then and now

So what does being Indian in the 1950s tell us about being Indian today? Quite a bit, I would think. As any viewer of Indian Matchmaking knows, the institution of arranged marriage within the “right” caste or religion is alive and well. I dare say Lata’s relationship with Kabir might receive the same response today. Just like in Seth’s book, landless tillers and Dalit leather workers might receive a sympathetic ear or financial support – but rarely a voice to speak for India. It is perhaps telling that the character Amit Chatterji is the one who gets to be the public face of India in the 1950s – is this so different from the people who speak for India today?

These are difficult themes to ponder and Seth handles them with a deft and light-hearted air. I found myself zipping through this very long book in a single weekend, and enjoying every second of it. And because this is a tale by Vikram Seth, the man who wrote The Golden Gate and Beastly Tales, it all comes with a generous dose of verse. (Amit Chatterji’s poem, the Fever Bird is my personal favourite). Do read it for a charming look at human relationships in a young and new India, still finding its feet.

Favourite quotes:

“The ifs and buts of history…form an insubstantial if intoxicating diet.”

“Why do you scream into my ear

What no one else but I can hear?”