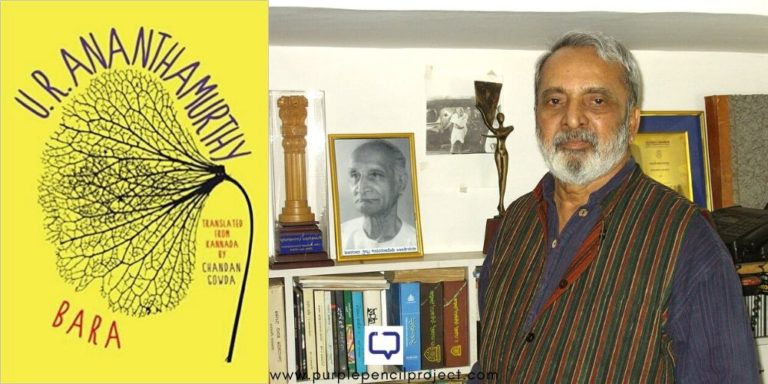

This book is an artistic treatment of lives at the margins

Gurdial Singh is one of the towering figures in Indian, not only Punjabi, literature. His fiction deals with the everydayness of life, and discusses the neglected, unseen, and unheard voices. Alms in the Name of a Blind Horse is one such celebration of a lifelong dedication toward rendering voice to the voiceless.

We encourage you to buy books from a local bookstore. If that is not possible, please use the links on the page and support us. Thank you.

At the start of the book a child is told the Hindu myth of ocean churning and distribution of Amrit between the Asuras and Devas. Latter-day Dalits are thought to be the progenitors of the Asuras. Without valorizing this myth, which among many other tools is a way to perpetuate caste-based violence, Singh weaves a long, almost never-ending, series of oppressions against the people at the margins.

Razed to the ground

As an upper-caste person, it would be gross to talk about caste. In the capacity of a reviewer, and someone who is informing himself about caste-based atrocities every day, I can say that this book is one of the rare feats in articulating Dalit lives in fiction in an artistic manner in which most oppressors’ tales are told and celebrated.

When I was tasked to write about this book, I was excited as I was to read yet another work by Gurdial Singh, one of my favorite Indian writers. But having read this book, I found myself crippled to handle this subject: What should I write? Should I begin by the juxtaposition of the Hindu myth with the modern-day reality? Should I talk about how the people in power, upper-caste people like me, use their privilege, and rob people of their right to justice? Critiquing oneself was the only way. And this review is just that.

One of the tools that the oppressors have in their hands is culture. The Hindu myth is that culture that Singh strikes a blow on by using it to tell a narrative, an age-old practice where Dalits go out on the day of lunar or solar eclipse to ask for alms.

Starting from Dharma’s kothas being razed to the ground to Melu’s drug-addict life in town and her wife’s helpless in front of her brother, in a deft sketch of an about-to-be-modernized Punjab, we witness the viciousness of this oppressive circle of caste in its raw form. The haunting imagery of kite, wild animals and monsters that disturb Melu during the night, or the dust storms, and the quietness and sudden uproar in the twelve-hour period during which this tale is set also reveal the tumultuous lives that people live at the margins.

The text and the translation

In the 2020 Actors A-List by Rajeev Masand, Nawazuddin Siddique says that our cinema is yet to appreciate and use ‘silence’ as a medium of communication. Rana Nayar, translator and a major literary figure, writes that “in this particular novella that Gurdial Singh has managed to strike a balance between ‘silence’ and ‘language’.” And it is indeed that quality that makes this work explosive.

But I’m not sure if he knows this, this narrative becomes weak in his translation. He pens down remarkable meditation about translation and translations, and the difficulties in unearthing the “cultural layers” in the original text that can sometimes “turn into a contraction or reduction, and at worst, a deflection, if not a total loss of meaning.” Whether what he wrote about translation was practiced is hard to tell. He’s not the only one to blame, however, supporting this poor translation is the editor, too, who, for reasons best known to them, has left unnoticed hundreds of ‘suddenly’. I don’t remember reading six ‘suddenly’ in two pages. Not only was it frustrating, but it also did injustice to a tale that must be read by all.

Best Quotes

“If someone says that ‘your beard shakes while eating,’ what explanation can you offer for that?” — Pala

Final Verdict:

Gurdial Singh’s Anhe Ghore Da Daan is a must read for its experimental approach in novel-writing. But Rana Nayar’s translation weakens this modern classic. I don’t rate books, but if I’ve to, then 5/5 for Gurdial Singh.

Disclaimer: The writer is an upper-caste queer writer.

One Response

FANTASTIC REVIEWS BY PASSIONATE REVIEWERS.

THIS ENDEAVOUR SHALL DEFINITELY ENCOURAGE READERS TO APPRECIATE INDIAN LITERATURE BUT HELP THEM AS WELL TO UNDERSTAND THE CULTURAL MORES & IDIOMS OF INDIAN SOCIETY.

THANKS

THANKS.