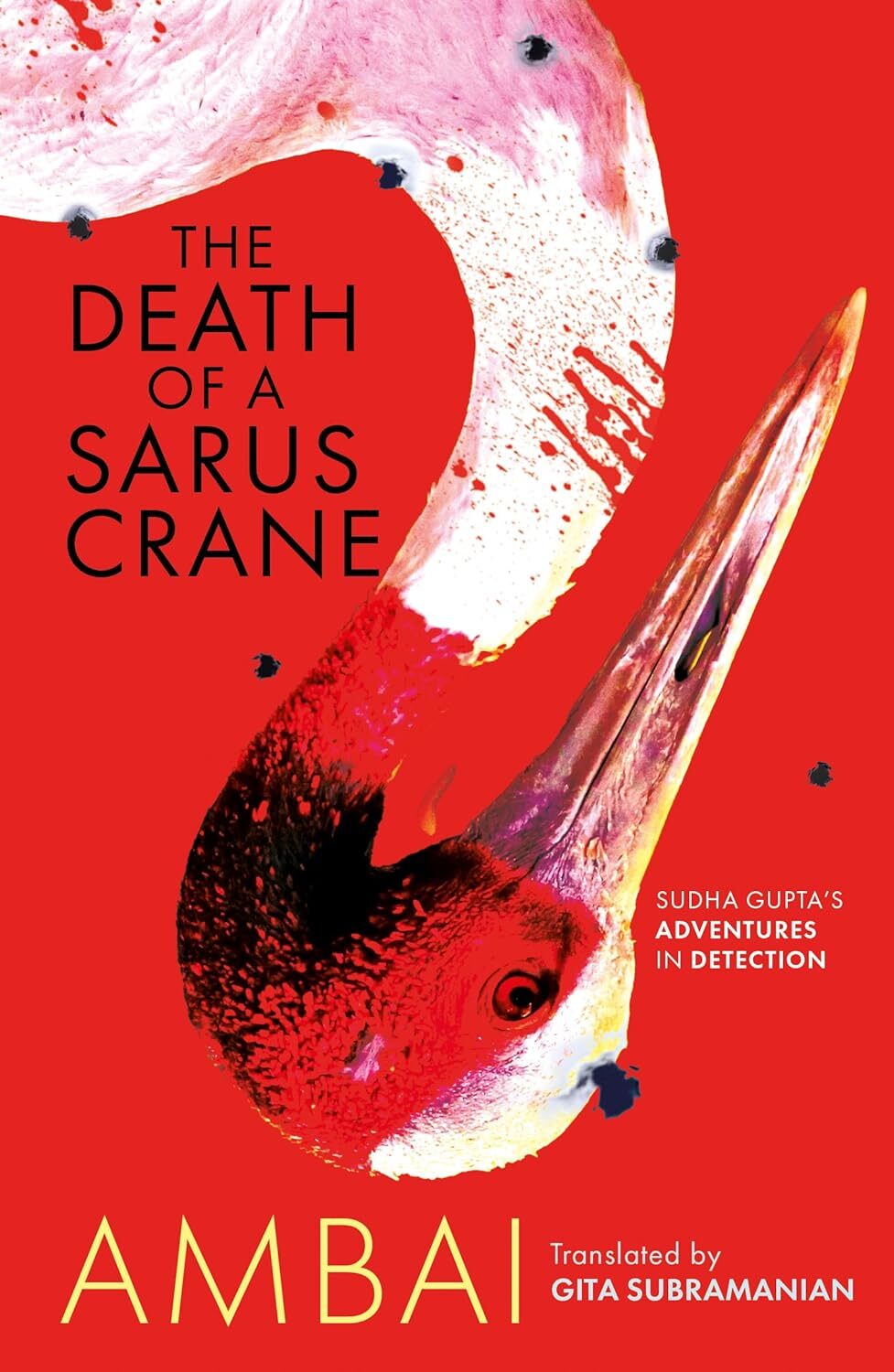

Amritesh Mukherjee reviews The Death of a Sarus Crane: Sudha Gupta’s Adventures in Detection by Ambai, translated from Tamil by Gita Subramanian (published by Speaking Tiger, 2024).

A gripe I’ve had with many Indian sleuths I’ve encountered over the years has been the derivative nature of their stories and surroundings. Granted, I need to read more Indian detective fiction, but the sleuth genre in itself is fairly new to the Indian subcontinent. From this perspective alone, Ambai’s Sudha Gupta is a joy to read for the local flavour in her stories (some might argue, perhaps a bit too local/Indian).

After all, she’s a cardamom tea sipping, gossiping about her cases in the evening, an English-peppered-with-Marathi speaking middle-aged woman who spends most of her time investigating businesses and spouses. Out of nowhere, “her cell phone sang, ‘Yeh moh moh ke dhaage.'” Heck, in one story, when an older woman shares her apprehensions about her son selling their home, Sudha advises her, “Aunty, think of your age. Pedru is your only son. Isn’t staying with him the right thing to do?” The right thing, indeed. It’s as Indian as they go.

Recommended Reading: A Night with a Black Spider by Ambai

Ambai’s Writing: Literary Detective Fiction?

All these contexts and nuances help create culturally rich stories that might not be more suited for fans of literary fiction over detective fiction. Which, given Ambai’s writing career, makes sense. Her writing reflects societal norms and the many restrictions placed upon self and what it’s allowed to do, often revolving around family and love with her uniquely feminist perspective.

She brings the same sensibility to the Sudha Gupta adventures, and these stories are more socio-political commentaries with Indian familial dynamics at their core than pure detective fiction, like your staple Christie or Conan Doyle or even Ray. Even the cases are usually commonplace, something you’d hear your family member whisper about. Talking about the cases, let’s look at each story briefly.

The Colorful Cast of Sudha Gupta’s World

Like many detective fiction stories, Sudha Gupta’s stories have a recurring cast of characters who bring a sense of familiarity and recall value as the reader moves through the stories. There’s Sudha’s assistant, Stella, her husband, Singaravelu, and her baby daughter, Anandi. There’s Sudha’s husband, the scientist Narendra, and daughter, Aruna. Her maid, Chellammal, also makes frequent appearances, as does her friend, ACP Govind Shelke, and her teacher, Vidyasagar Rawte.

This motley of characters lends these stories a warm touch, each with their eccentricities and perspectives.

A Closer Look at Sudha Gupta’s Cases

The opening story, “A Room Measuring 250 Square Feet,” finds a young man dead, alone in his tiny apartment. As relatives rally outside the hospital to inherit his room (buying even a room in Mumbai is no mean deal), the police reach out to Sudha for help. As she discovers the young man’s family and background, secrets keep falling.

The titular story, “The Death of a Sarus Crane,” my favourite and also the longest story in the collection, has an 11-year-old girl dead in an apartment, with Sudha’s husband’s friend’s wife (wrongly?) arrested for her murder. Murder or suicide? Insider’s job or something more pre-planned?

The Indian society forbids love in many ways. The next story, “Sepal,” is a story of some of those forbidden loves, where Sudha’s cook’s daughter tries to commit suicide. As past and present merge, many secrets come to the fore, reflecting the societal pressures that lead people to strange alleys.

The final story, “Bun, Maska and Irani Chai,” features a Mangalorean Catholic woman who asks Sudha to investigate a potential foul play that might uproot her from her home and city. It has an all-too-familiar premise at its core and perhaps a similarly familiar climax.

Recommended Reading: 8 Contemporary Indian Fictional Detectives

The Underlying Societal Layers in the Collection

Mentioning the themes of each story would partly reveal their mysteries and unravellings, hence the need for a separate section. The collection features a myriad of social themes, including, but not limited to, LGBTQ+ discrimination, the divide between the rich and the poor, racism, and sexism. Ambai uses the crimes/conflicts to highlight the contradictions and paradoxes inherent in our society and rarely do you read something you wouldn’t have encountered around you or in the news at some point or the other.

And when he married Manjula, who was poor, without letting them know first, it was like a great betrayal, as if he had destroyed the nest that he lived in. Manjula, to her, was from a different bird species. She did not belong to this nest.

– Ambai, The Death of a Sarus Crane

The sensitivity with which Ambai tackles these complex themes amidst even more complicated societal dynamics is beautiful. While her writing reflects the persisting issues in our surroundings and nation at large, it also attempts to create a more inclusive, liberal world, one not divided by a myriad of boundaries and prejudices.

Moreover, the collection conglomerates different languages and cultures, from Konkani to Marathi and Jaipur to Mumbai. As our detective resides in Mumbai, the peak of Indian multiculturalism, the stories get a free hand to interact with varying backgrounds and lifestyles, which only adds to the reading experience.

Favourite Quote from The Death of a Sarus Crane: Sudha Gupta’s Adventures in Detection by Ambai

Among married couples, if one dies and the other survives, we say the survivor is widowed. We call her a widow and him a widower. But in our kind of relationship, if one dies what is the other? I have found a suitable word for that. That word is Sunanda. A word that contains all the happiness and the sorrows of the world. After you, I have become a Sunanda. (…)

Now I am still here. I, a Sunanda.

Conclusion

Ambai’s The Death of a Sarus Crane is an immensely readable, eclectic collection of short stories ideal for beginners and regular readers alike. Gita Subramanian’s translation from Tamil into English is great, as she preserves the many regional flavours characteristic of the Sudha Gupta stories. With characters who would sound familiar to many readers, Ambai pens stories that are as mysterious as a means for a larger social commentary. So, come for the thrill, stay for the dynamics?