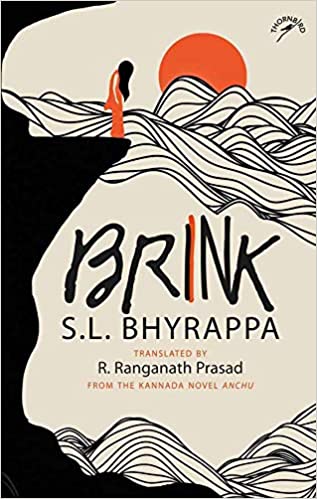

Translated from Kannada by R. Ranganath Prasad

Originally published as Anchu in Kannada by the legendary S.L. Bhyrappa, Brink is a love saga set in Mysore, a love between an older couple, a journey of learning to love someone with anxiety, a journey of loving life that has not been kind to you, and finding a way to move beyond deceit and learning to trust again.

We encourage you to buy books from a local bookstore. If that is not possible, please use the links on the page and support us. Thank you.

(Below: A map of the locations where the novel takes place)

So, what’s happening?

Amrita (mother of two) and Somashekhar (widowed) meet perchance on a sunny day in Mysore; Amrita’s home needs fixing, and Somashekhar is a reputed architect. It’s love and connection at first site.

Brink follows her struggles with depression, the committment to life and love that she shows towards Somashekhar, his struggle to find the right way to be with this person he is in love with and recognize the difference between her arrogance and her anxiety, and her journey to tie the loose ends of her life that keep her from moving on, and forward, in a meaningful way.

Meeting Amrita

While a love story between a man and a woman, Brink is fundamentally a powerful read on Amrita’s relationship with herself, and a note on how important it is to be at peace with your own context before you can join with another (To the point of feeling like Somashekhar’s world has been excluded).

Written in a stream of consciousness ( a style I have not often read in Indian literary works), and with a powerful abandon, Bhyrappa invites us to meet some of the most intimate depths of her heart and mind, and follow her on her journey to make the life she wants – sometimes behaving rationally, sometimes not, but always being true to herself.

It is Amrita who pursues Somashekhar, she who waits for him when he does not show up for their afternoon rendevous in her house, she who calls him first after a fight, she who waits for him before having lunch (as a symbol of thoughtfulness, not subjugation), who obsesses over him with all the rationality, silliness, and a touch of toxicity that comes with it. She calls the shots.

“Get up and come here,” he scoffed at her.

“Don’t command me. I give a damn for orders,” she retorted.

But she must also face the loneliness of being a mother and having to love unconditionally – her sons, 8 and 4, miss their father, have been provoked to think ill of their mother by the grandmother-figure in their life – and yet she must put up a brave face, participate in their stories and life with the vigour of happiness.

And if this was not enough, a crucial sub-plot has her fighting to get out of the financial and moral deception that her aunt, who had only pretended to love her like a mother since childhood, had carried out for many years mooching off her coffee estate.

We see very little of her life as a professor, which feels at once like sexist representation of Amrita, but also natural, since she had given it a backseat to raise her two children.

Mental wellness as a literary theme

I am not qualified to comment on the how close to reality Amrita’s depression has been portrayed in Brink, but it is the most nuanced look into mental illness in Indian cultural life at large – be it films or books.

Bhyrappa’s words and Prasad’s translation of Brink lays out the full breadth of her expriences; the many suicide notes she has kept ready, the stash of knives she keeps in her bedroom, the loaded revolver that is always at hand, how she debates between shooting herself in the temple, versus the mouth, versus the heart, how she finds herself in a void between life and death and needs an escape, how she projects these anxieties and insecurities on her relaltionship with Somashekhar.

But at no point, do they become and excuse for her anti-social behaviours or mood-swings – they are the reasons, and she is fighting them in her own way, and she is figuring the web of problems out and untangling them the best she can.

A translator’s got to do what he’s got to do

What will hit you the most from the word get go as you read Brink is the unusual style and flavour of Prasad’s translation. While it does not always flow as smoothly (several sentences sound downright academic), the rest of the choices are interesting – the near absence of pronouns (and objects in the sentence, for the grammar nerds), as well as phrase-like abruptness of the sentence construction, and words used in unusual and inventive ways.

So “the world thaws and the horizon distorts“, one “dissects” the other when talking about getting to know them, and characters simply declare, “Feel like penning a ghazal” or “Relationship to the extent required only“.

This style, its passive tone, reminded me of how 50-60 year olds, who very much learnt English as a second-language spoke (unlike the post-1990 generation which also learnt the culture that the language inhabited). It’s highly colloquial, rudimentary to sound but technical in correctness – as a translation, it worked wonderfully for me. It captured the voice of our two main characters with a richer intimacy that most Indian writing in English does.

But…

It’s not perfect; the way their sexual activity is described could have been more lucid and less like an academic disposition, archaic words like “cometh” and modern colloquilisms like “Hey dude” are sprinkled throughout, uncharacteristically.

Conclusion

There is a lot to say about Brink, but all you need to know is this; do not miss this one. If you want to read about the struggles of depression, how love listens and responds to it, and also, just of an era and culture of dating that is never unsure about its feelings, this book is for you. Also, one of the most powerful female leads in Indian literature!

Favourite Quotes

On the difficulty of finding an expressing the artist’s voice

The moon’s fate is his, and as she thought of him as an unfortunate fellow without a home or family, she felt like expressing that in verse. It stayed on for quite some time, feigning a certain rhyme. But even the first line did not take shape.

On the nature of love

“Tell me what you felt when you saw me that day.”

“What shall I say?”

“Nothing”

“If you got no feelings at first sight, you will never get anytime later.”

2 Responses

Thanks for your review. Instead of just using some adjectives (dry/ bouncy etc.), you have exemplified your observations/ analysis, and that makes possible the mending and honing of my language. I will keep it all in mind.

Thank you for being so gracious about it sir! I look forward to reading more of your work!