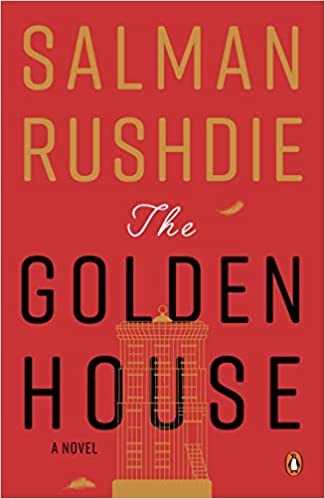

Think of Salman Rushdie’s The Golden House as a travelling theatre and a mobile culture library, situated primarily in the Macdougal-Sullivan Gardens Historic District or simply the Gardens, and making interim stops at the rest of New York and Bombay.

We encourage you to buy books from a local bookstore. If that is not possible, please use the links on the page and support us. Thank you.

Or

Think of the narrative as a collective dream coming crashing down, a dream the world dreamt for itself, of creating a new world according to its own rules.

Or

A garden, a garden of history and the present, a garden with boundaries of philosophy and history, of Roman emperors, Greek mythology, terrorism, culture, Bombay, New York, Identity, folklore and mystic arts. Each brick holds its own importance on these walls, and you can remove anyone and peek into the life of Nero Golden through that prism. Sometimes, it may just be best to break the walls down. For the grander picture.

Or

Simply, the story of a family that tried to run away from its past, but could not.

Or

The prophecy of an America where one could no longer take a new identity. It was not the land of the escaped anymore. It had its own history now, and no one, without permission of the white men, could add their chapter to its book. It was not the new world anymore.

Or

A giant chessboard with each piece representing a world of a world and the king playing to self-destruction.

This dream includes within this garden there are, like backyard gnomes, this community includes Nero Golden the king-in-exile, his sons who take the names of Petya, Apu and D (or Petronius, Lucius Apuleius and Dionysus), their respective women Vasilisa,

Ubah Tur, Ubah Tur and Riya Z. The narrator is Rene, his parents, and his girlfriend Suchitra Roy. And performers who help this star cast amble along.

Beginning with the arrival of Nero Golden in the Gardens, escaping an Indian past, this grand picture, for it is more a directed novel than a written one, this grand picture weaves a tale of crime, art, morality and politics (It covers the years between Obama’s inauguration and Trump’s electoral victory).

The tale unfolds as an answer, or an attempt to answer, two questions:

What is a good life? What is its opposite?

What is heroism? What is villainy? How much have we forgotten if we don’t know the answers to such questions anymore?

Nero is a criminal escaping, Rene an aspiring film-maker, living with his parents (a refreshing change), who observes The Goldens and decides that their story will become the subject of his documentary. For this, he must get to know the true selves of these four men, each of whom lives in a world of his own.

If Nero lives in a world where he is still an important king, Petya the agoraphobic brother lives in a world of walls and blue lights and is away from open spaces, sometimes offloading, sometimes shutting up within his brilliant mind.

Apu lives in the liminal space between the world of real beings and the world of his art, a second plane where all his experiences are physical manifestations he can feel as ghosts. Causing a rift between these two real brothers is Ubah Tur, an artist exemplar and breaker of Petya’s heart, winner of Apu’s. D, half-brother to the elder two, who is a man who may not want to be a man, who finds Riya the curator of the Museum of Identity and who learns the difficult, the new vocabulary of those neither female nor male or both, or none.

This is not a thriller, this is not a crime mystery. This is a story of the lives of criminals after the crime is done, and he has escaped. Nero escapes from the Z company after helping orchestrate the 1992 Mumbai riots following the demolition of the Babri Masjid. This Dawood-Chhota Rajan-Chhota Chetan brand of criminals strike again in 2008, and Nero helps this monstrosity too. And then he goes away.

Goes to America that land of the self-made self, that land whose peoples picked their own identities, “shedding their Gatz origins and becoming shirt-owning Gatsbys”. Nero wants to recreate his own identity, and so does Vasilisa the beautiful Russian who wants her looks to get her a high position in life.

Here, as the sons’ identities reveal themselves, as they cope with this uprooting, he struggles to keep his new and old life seem effortlessly joined at the seams. Petya and his increasing insanity, his fear getting the better of him, his powerful, explosive brain struggling to find a balance. Apu’s visions, D’s gender confusion. And Vasilisa, with the new baby Vespasian.

But the guns follow him everywhere, and so does the fire. Only that which is not gold survives. The king burns in his castle of gold.

But outside, outside there is another, as America reveals its own ‘secret identity. Not a superhero, but a supervillain’. Trump’s rise, using the allegory of The Joker, Brexit and the changing idea of America, this new America that was not an open book for anybody to escape to and add their own chapters, but one which was, like the older countries, a book with history, and therefore, needed to be whitewashed.

“The America I loved, gone with the wind.”

Or

“I want a hero an uncommon want,

When every month and year sends forth a new one,

Till after cloying the gazettes with cant

The age discovers he is not the true one.”

Society and the individual are at constant loggerheads with each other, and so are the individual selves of the characters. Even as the world opens up to the ideas of expanding gender roles, the individual questions the possibility of good men being bad, bad men being god, and of heroes and villains changing disguises. Sometimes, this period between the old and the new ideas is impossible to navigate.

When “It s who I am, it is who she is.” When this duality of realities fights each other.

That’s when you kill yourself.

Sometimes, the past kills you. And sometimes, life throws you at a curve only when you begin to embrace it. Those that have had their share of life will play the violin at the edge of death, and those that were really close to their dreams will leave some part of themselves behind to continue in some form to exist in this real world.

“This is the most immediate fruit of exile, of uprooting, the prevalence of the unreal over the real,” Rushdie quotes Primo Levi.

What is real? The ghosts of evil or evil itself? The movie or the life? Is the movie an imitation of life, an exaggeration, or is all of reality a made-up cosmic fiasco? How can we trust Rene, who so openly wanted the loopholes in his story filled, that he went ahead and filled them and gave a note of caution, but who reads the fine print on 70mm? Like Suchitra tells him,

“The movie is about you and all the people are aspects of your own nature.” What if Rene too has jumped into the reality of his own film and refuses to show us any other version?

Rene’s movie makes the larger arc and becomes eventually the raison d’etre of their American existence, and Rene and Apu move among the artistic elites. Fittingly, we see references to cultural icons across media from Byron to Herzog, Moby Dick to Goodbye to Berlin, The Purple Rose of Cairo to Bob Dylan, from Kurosawa to the Beatles, from Jean-Luc Godard to The Godfather (of course The Godfather), from Shakespeare to Flash Gordon, from Sundance to Tribeca, from Kafka to Gangster (starring Kangana Ranaut) from Tu hi meri shab hain to Parveen Babi to Dilip Kumar and the nexus between the Underworld and the Bombay film industry and Borges and Eisenstein and Nine Inch Nails.

Salman Rushdie, in Haroun and the Sea of Stories and Luka and the Fire of Life, has

shown us he likes to pack a lot of knowledge in one book. So all these movie references, so all the places in Bombay; from the Aer Lounge to the Leopold Cafe. So also the plays of Aeschylus and Sophocles, so also the films of Woody Allen and Hitchcock and Satyajit Ray. As also Apoorva Lakhia and Sanjay Gupta and Ram Gopal Verma (written in our copy as Raj Gopal Verma).

At the end of it, it is a grand book. With a simple plot of exile, yes, but it talks of the what after the crime? What after the greed? What after the villainy? Can we retain our good selves after the wrongs we commit?

It talks of white and saffron, of green-haired purple-coated Jokers, of alienation of the grand whirlwind our lives are, and how as the big and powerful go around spinning their webs, defining eras, and civilisations with their acts, we individuals will return to our homes, our lives, the only thing we can make sense of.

Favourite Quote:

But if human nature were not a mystery, we’d have no need of poets.

Recommended Age Group: 21 and above