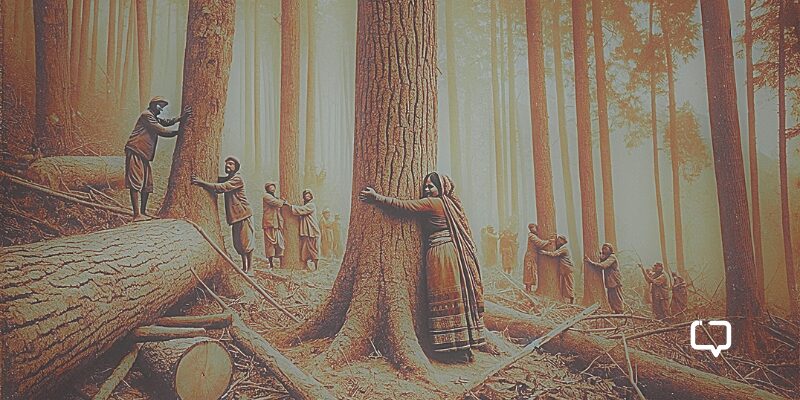

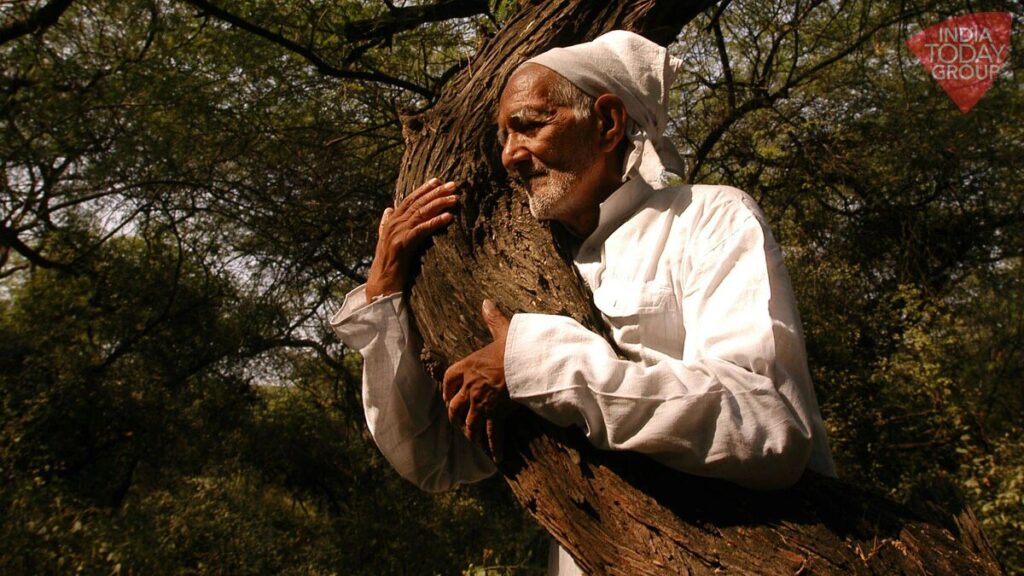

In 1973, the quiet hills of Uttarakhand’s Chamoli district were the site of one of the largest grassroots environmental protests. Local communities sparked a nonviolent resistance to protect their forests, threatened by rampant deforestation, endangering the livelihoods of local communities who relied on forests for essentials like timber, firewood, and water. Led by Chandi Prasad Bhatt and Gaura Devi, villagers embraced the trees—literally.

“Chipko” actually means “to hug” in Hindi, and that’s exactly what the villagers, particularly the women, did: they hugged their trees to save their forests and their livelihoods. Chipko showed the power of the connection between people and the environment, ultimately forcing the government to stop commercial logging in the region. Today, it symbolises grassroots activism globally, inspiring movements everywhere. It’s proof that sometimes, a simple hug can change the world. We explore the many facets of the movement in detail through this essay, from its origins to its relevance in the 21st century.

The Roots of Resistance

The Chipko Movement sprang to life in the early 1970s in Mandal village, located in Uttarakhand’s Alaknanda Valley (then part of Uttar Pradesh), as a direct response to the destructive flood of 1970. This disaster, worsened by industrial logging, killed about 200 people and woke the local community up to the dangers of unregulated deforestation. These forests were vital to everyday life, supplying essentials like firewood, fodder, and medicinal plants.

Chandi Prasad Bhatt, a Gandhian environmentalist, was at the forefront of this movement. He’d already set up the Dasholi Gram Swarajya Sangh back in 1964 to support village industries using forest resources, but the escalating deforestation pushed him to organize the villagers against the loggers.

Foundations and Influences

The movement was deeply rooted in Gandhian nonviolent resistance or satyagraha. Leaders like Bhatt and later Sunderlal Bahuguna championed peaceful protests. They famously embraced trees to block loggers—this act of hugging trees symbolized their fight to protect their natural rights, echoing Gandhian ideals.

Where Chipko Began: April 1973

It all started in April 1973, when Bhatt and his followers opposed a government decision to allow a sports goods company to log extensively in their forests. The community’s pleas were initially ignored, so they took a stand by wrapping their arms around the trees, successfully stopping the logging. This victory not only saved the trees but also set a precedent for future environmental movements.

Recommended Reading: Resistance Literature in India: Through the Years

This initial protest in Mandal ignited a broader movement, quickly spreading to other villages in the Himalayas and involving many local women who were heavily impacted by deforestation. Their participation highlighted the movement’s wider impact on environmental and community rights.

Defining Events in Chipko’s Journey

Why was the Chipko Movement one of the most influential grassroots environmental campaigns in the world? Because of an interplay of ecological necessity, gender dynamics, and non-violent resistance, as we see below.

The Initial Standoff: The Mandal Incident (1973)

The Chipko Movement’s first major confrontation happened in Mandal village in April 1973, and it is largely considered the turning point in the environmental protests in India. Gaura Devi, a local leader of the Mahila Mangal Dal (Women’s Welfare Association), led 27 women to physically embrace the trees in the forest to stop the loggers.

These women were primarily motivated by the economic and ecological importance of the forests to their daily lives—they relied on the trees for firewood and fodder and to prevent soil erosion and landslides in the steep, mountainous region. Despite threats from the armed loggers, Gaura Devi and the women stood their ground to protect the trees. This confrontation successfully halted logging operations while bringing national attention to the movement.

Recommended Reading: The Great Smog of India by Siddharth Singh

A Movement Takes Root: Expansion Across Uttarakhand (1973–1980)

Post-Mandal, the Chipko spirit spread like wildfire (pardon the pun!) across Uttarakhand, from Reni to the Henwal valleys. Reni, a village in Chamoli, became iconic in 1974 when Gaura Devi and local women once again played a crucial role in stopping loggers from felling over 2,000 trees. The movement’s growth resulted in further debates on sustainable development and maintaining ecological balance in the Himalayas. Under leaders like Chandi Prasad Bhatt and Sunderlal Bahuguna, these protests evolved from local skirmishes to a significant environmental crusade, leading to a 15-year moratorium on tree-felling by the Indian government.

Women: The Heart of Chipko

A remarkable aspect of the Chipko Movement was the central role played by rural women. Women like Gaura Devi, Bachni Devi, and Sudesha Devi were the drivers behind many protests. Their intrinsic link to the forests, which supported their families and communities, made them natural leaders in the fight against deforestation. Their participation highlighted the role of ecofeminism and how environmental degradation disproportionately affects women and marginalized communities. This gendered dimension adds a layer to the movement’s impact and underscores the influence of Chipko on women globally.

The Faces Behind Chipko

While the movement was largely people-driven, these key figures were instrumental in making the Chipko Movement successful.

Chandi Prasad Bhatt

A founding figure of the Chipko Movement and the man behind the Dasholi Gram Swarajya Sangh (DGSS) since 1964, Bhatt’s vision is to empower local communities through sustainable forest-based industries. Under his leadership, the DGSS boosted local employment by using forest resources innovatively. He led the first Chipko protest, and over the years, Bhatt’s work has halted deforestation and earned honours like the Ramon Magsaysay Award and the Padma Bhushan. He’s also initiated multiple tree-plantation drives, especially encouraging women’s involvement to restore the Himalayas’ ecological balance.

Sunderlal Bahuguna

Sunderlal Bahuguna, a disciple of Gandhian philosophy, took the Chipko spirit nationwide with his epic 5,000-km trek across the Himalayas between 1981 and 1983. This journey was a movement in itself, highlighting the role forests play in sustaining the environment. Bahuguna’s interactions, including a notable one with Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, influenced the 1980 ban on commercial tree-felling. His “What do the forests bear? Land, water, and fresh air!” was a rallying cry of the movement. Bahuguna blended environmental advocacy with a push for sustainable community livelihoods and left a major impact on India’s forest policy.

Gaura Devi

Gaura Devi, from Reni village, might not have seemed like a typical activist, but in 1974, she became a legend. Leading a band of women, she stood firm against loggers, physically shielding the trees with their bodies. This act turned a local protest into a national movement and shone a spotlight on the immeasurable role of women in environmental activism. Devi’s bravery spurred a wave of female-led protests across the region, proving how the most effective guardians of the forest were those who depended on it the most. Gaura Devi’s actions symbolise grassroots activism and the ability of local communities, particularly women, to lead environmental protests.

Chipko’s Impact on Law and Policy

The governmental response to Chipko, both in India and internationally, truly showed the incredible growth of this local movement into a global symbol.

The Movement’s First Success: 1974 Logging Reversal

The Chipko Movement achieved its first significant success in 1974 when the grassroots protests led by Gaura Devi in Reni village halted the planned felling of over 2,000 trees. The uproar was loud enough that the Indian government couldn’t ignore it—they had to revoke the logging rights in that area. This marked a shift in policy as the government began to take local concerns about deforestation more seriously.

Legislative Impact: Forest Conservation Act (1980)

Riding on the momentum, the Chipko Movement pushed the Indian government to enact the 1980 Forest Conservation Act. Under this act, the government placed a 15-year ban on the felling of green trees above 1,000 meters in the Himalayan region, protecting large swaths of forest from commercial logging. This policy was critical in balancing environmental protection with development goals. The Chipko Movement’s success in influencing this legislation was the perfect demonstration of how grassroots efforts can lead to major national reforms.

Recommended Reading: 7 Translated Indian Eco-Fiction

Chipko’s Impact on International Environmentalism

The Chipko Movement’s principles of nonviolent resistance and community-based conservation efforts received international attention, sparking environmental movements far and wide. It was one of the earliest movements to link local ecological struggles with global sustainability, shaping the environmental discourse on how indigenous and marginalized communities play a crucial role in stewardship. Beyond changing policies, the movement set the stage for community-focused global environmental policies.

The Legacy of Chipko: Then and Now

While the Chipko Movement greatly impacted environmental policy and inspired countless movements, it also struggled to balance environmental conservation with the economic needs of local populations, as we see in the subsequent sections.

Sowing Seeds of Environmental Consciousness

The Chipko Movement really woke people up to how crucial forests are—not just for the environment but for the survival of rural communities, particularly in the Himalayas. After all, forests provide everything, from water and soil stability to clean air.

Through its nonviolent tactics and grassroots mobilization, Chipko showed that environmental conservation wasn’t just a concern for the elite or urban populations—it was a matter of life and death for rural communities that relied on natural resources. The movement inspired national policies, such as the 1980 Forest Conservation Act, which curbed deforestation and protected biodiversity in ecologically sensitive regions.

A Movement That Sparked Many

The Chipko Movement set a powerful precedent for future environmental and social movements in India and globally. Its ripple effects inspired the Beej Bachao Andolan (Save the Seeds Movement), which advocated for traditional agriculture and biodiversity, and the Appiko Movement in the forests of Karnataka. The movement also set a precedent for more women to step up in environmental activism globally.

Internationally, Chipko showed how local, community-based movements could challenge big commercial powers. Grassroots efforts worldwide, including those addressing deforestation, climate change, and indigenous rights, have drawn from the Chipko model of nonviolent resistance and community empowerment.

Chipko’s Struggles and Criticisms

However, despite its celebrated successes, not everyone felt Chipko achieved its goals. Critics like Shamser Singh Bist believed it fell short economically for local communities. The strict tree-cutting ban was great for forest conservation but limited locals from developing forest-based industries. This led to dissatisfaction among some villagers who felt that their economic needs were sidelined. Additionally, some argued that a stronger political strategy, both locally and nationally, could have amplified the movement’s impact to ensure more substantial, lasting benefits for the communities.

Essential Reading on the Chipko Movement

The following works are critical for a nuanced understanding of the movement’s origins, key figures, and its imprint on Indian environmental policies. For a thorough, multi-dimensional view of Chipko, read them.

1. The Chipko Movement: A People’s History by Shekhar Pathak

Often considered the most authoritative history of the Chipko Movement, Pathak’s work deeply explores the lives of grassroots activists, with a special focus on the women behind its success. Translated into English by Manisha Chaudhry, the book got the Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay NIF Book Prize in 2022.

Thanks to Pathak’s thorough fieldwork, interviews with protestors, and investigations through local newspapers, it’s an invaluable resource for anyone looking to grasp the full scope of Chipko’s impact on environmental activism. The narrative doesn’t stop at famous leaders like Chandi Prasad Bhatt and Sunderlal Bahuguna, also focusing on lesser-known heroes like Gaura Devi, whose leadership was crucial during key moments of the movement.

2. The Unquiet Woods by Ramachandra Guha

While Guha’s book isn’t just about Chipko, it extensively covers forest-based resistance in Uttarakhand. His debut work explores the deep roots of peasant environmentalism, with the Chipko Movement spotlighted as a key episode in this lasting struggle.

One of the earliest books on environmental history in South Asia, Guha analyses the socio-political and environmental backdrop that sparked Chipko through this critically acclaimed book.

3. Environmental Movements of India by Amsterdam University Press

This book situates the Chipko Movement within the broader context of India’s environmental struggles, like the Narmada Bachao Andolan. It presents a comparative look at how Chipko shaped environmental policies while inspiring other grassroots movements.

The discussion also extends to the philosophical and ethical underpinnings that guided these movements and their ties to indigenous practices and community rights.

While these books help you better understand the Chipko movement, they also give you a somewhat comprehensive idea of the history of Indian environmental movements over the previous decades.

Conclusion

Even 50 years later, the spirit of Chipko is very much alive in many parts of India and the world. Its core principles still fuel resistance against environmentally damaging activities, whether it’s major deforestation or risky infrastructure projects in delicate ecosystems. Today’s pressing issues—climate change, biodiversity decline, and worsening air quality—only deepen the relevance of Chipko’s teachings. The movement’s focus on empowering local communities and championing environmental stewardship aligns perfectly with today’s push for community-driven sustainable development.

The Chipko Movement was a catalyst that sparked a global dialogue on sustainable development. It remains a prime example of how grassroots activism can bring substantial change, reinforcing the tenet that true development should balance progress with environmental preservation.