“You should have seen them scrambling for his presents – all except Mr. Kips – he had to go to the lavatory first to vomit. Cold porridge hadn’t quite agreed with him”.

Graham Greene, Doctor Fischer of Geneva

I cannot say with any certainty whether something as unsavoury as this was served at the recent gala wedding of the son of who is popularly called, “India’s richest man”, which is all that one can read in tabloids and social networks. But it is hard to ignore a very recognizable parallel that one can find between one of the fictional parties of Doctor Fischer, the toothpaste tycoon of Geneva, and the wedding party hosted by Mr. Mukesh Ambani.

There might not be any abject humiliation on display here, nothing on the scale of cold porridge, certainly, but the often-replayed scenes of actors and celebrities dancing on a stage, entertaining simply the whim of the rich and powerful man pulling their strings, are bitterly ironic: while Mr. Ambani might not have quite made his guests catch and cook live lobsters, like Doctor Fischer, he would certainly have liked to rule them all “as a man might rule a donkey with a whip in one hand and a carrot in the other.”

And, as evidenced by the almost desperate enthusiasm of these guests, one can say quite safely that though they are “well-lined themselves”, they certainly do enjoy the carrots, which might include, quite plausibly, flights in private aeroplanes and fees even more exorbitant than any film producer would have thought of.

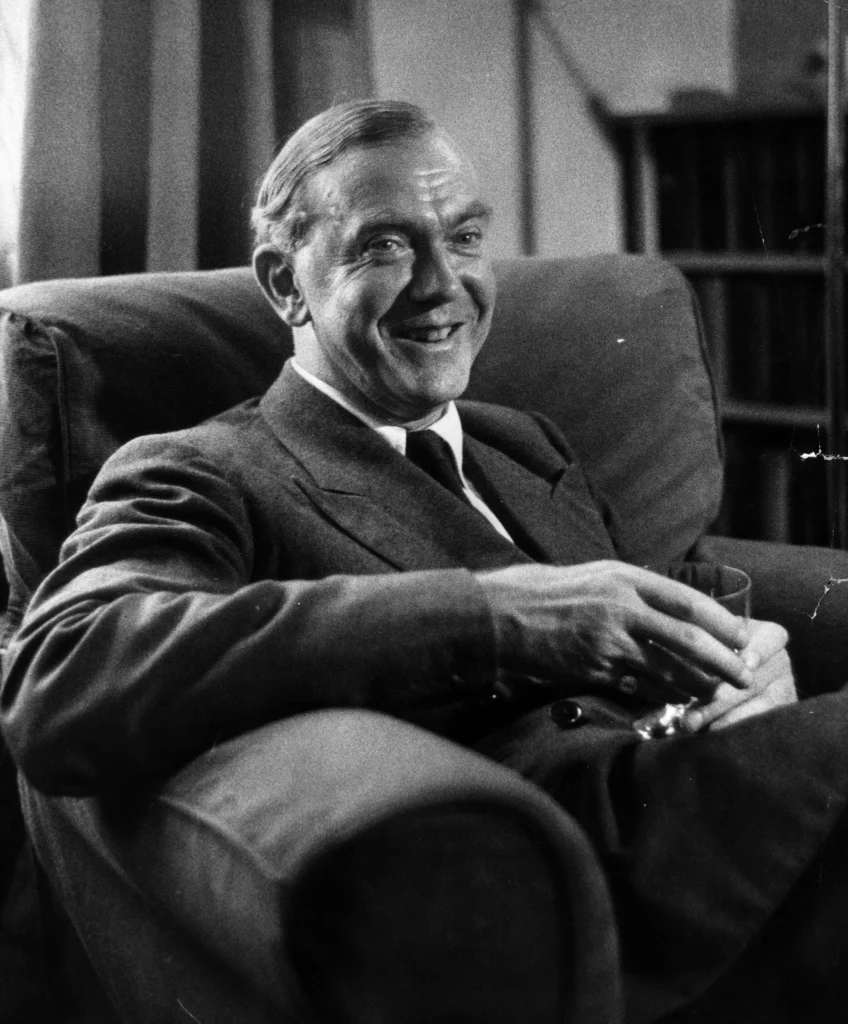

Sir Alec Guinness, that fine actor, called Greene “a prophet” and indeed, that prolific man of letters, possibly the greatest and most consistently exciting of the previous century, was something of an eerily prescient soothsayer of many a major and even cathartic upheavals of his times – the ignoble and even suicidal denouement of the Vietnam War, the paranoia of nuclear destruction reaching a boiling point with the Cuban Missile Crisis; unlike a prophet, however, in the sense of a Nostradamus, Greene never merely condemned his fellow mere mortals to a dark fate but rather understood its capacity for both sin and redemption, being himself a man not invulnerable to flaws and failings.

Not since the times of Dickens and Stevenson has there been a writer with such a gift for both an empathetic and realistic portrait of moral complexity; he was also the only writer since Conrad to endow an all-encompassing sympathy to the mere mortals who populated the so-called “third world” of our fact and fiction. And, as an astute observer of the many struggles of power, religion, ambition, and morality unfolding in the twentieth century, he was always willing to contend for and defend the fallen, the outlawed, the betrayed against the vanity of the rich, the righteous and respectable, even as the latter always will be, in a touch of tragic realism, invincible in the end.

“Now they are not the cheapest and the best – they are the only. Krogh’s in France, in Germany, in Italy, in Poland; Krogh’s everywhere. ‘Buy Krogh’s’ has a different meaning now – ten percent and rising daily.”

Graham Greene, England Made Me

“Self-made” Billionaires and Erik Krogh

Such is the vaunted omnipotence of Erik Krogh, possibly the first of the mercurial and even unscrupulous men of power and wealth whom Greene knew how to deconstruct so skilfully. The Swedish financier, inspired by the real-life Ivar Kreuger, who makes dubious financial arrangements unblinkingly and yet wonders whether the fountain in his basement looks any good, does not seem too dissimilar from any of those self-made billionaires of today, wielding a ubiquitous influence and inwardly alone and in the throes of self-doubt and disillusionment.

“‘I don’t understand poetry’, he said reluctantly. He did not like to admit that there was anything he did not understand; he preferred to wait until he had overheard an expert’s opinion which he might adopt as his own but one glance at the room told him that here he would wait in vain.”

Graham Greene, England Made Me

From the ‘omnipotent’ yet ‘ignorant’ Krogh, who is bored even by opera, to the sneering, almost sadistic Doctor Fischer, who could not even understand the beauty of Mozart, lies a journey of nearly forty-five years during which Greene found himself challenging the autocratic tyranny of many a dictator – Batista, Papa Doc Duvalier and General Stroessner.

Recommended Reads: On Reading Novels

It is to his credit, however, that even as the titular tyrant, who demands his ‘Toadies’ to submit to his cruel amusements, is an intimidating, almost Machiavellian figure, he is nowhere as invincible or even inhuman as the likes of Ernst Stavro Blofeld or even Don Corleone. Apart from the five utterly servile and shamelessly sycophantic Toadies attending his parties almost religiously, he has no other friends; his wife, and subsequently his estranged daughter’s, death only leaves him more bitter towards the world and imprisoned in his solitude.

A lonely man playing at being God – how frequently we have met this character in Greene’s fiction – the crime boss Colleoni only faintly threatened by Pinkie Brown’s ruthless ambition, the seedy Syrian smuggler Yusef who holds Scobie hostage to his inexorable scheme of blackmail and disgrace out of a perverse desire for friendship, even the kind, if incurably absent-minded, Dreuther in Loser Takes All, dubbed as the Grand Old Man, or Gom, does not escape Greene’s or his protagonist’ infuriated sense of anguish.

“He makes the world and then he goes and rests on the seventh day and his creation can go to pot that day for all he cares. If only, for one moment, I could have had him in my power…it was as if I was doomed to be an idea of his, he would never be an idea of mine.”

Graham Greene, Loser Takes All

Though this is a protest at Gom’s absent-mindedness, one could almost replace the “m” with “d” and the rant would still resonate like how the protagonist of The End of the Affair almost rallies against God himself, imploring him to leave him alone.

And just as the Gom’s arrival is too late to rescue the helpless man and his almost imperilled marriage, Doctor Fischer too likes playing God to exact his vengeance, as he remarks, “he can only be greedy for our humiliation”, Fischer himself is greedy for humiliation, of those whose greed, almost insatiable for his expensive gifts, is no less hideous.

But behind this greed of his lies coiled a sense of disappointment all too human – of a loss, a vacuum, an irreparable absence of love and warmth that is mirrored, during the course of the story, in the life of the man who narrates the novel – Alfred Jones, a mild-mannered writer of letters for a chocolatier, who marries Fischer’s defiantly kind-hearted daughter and thus also condemns himself to that same cathartic fate filling him with a different sort of greed for death.

Doctor Fischer of Geneva or The Bomb Party

The subtitle of this slender but profound novel – the Bomb Party – is the scene of the ultimate test of these different degrees of greed: Fischer’s lust for humiliation, Jones’ thirst for death and the Toadies’ ludicrous greed for those expensive presents. What follows is a sinister game of Russian Roulette – not unlike the games that Greene himself played out of boredom in his adolescence – with the six chambers replaced by six Christmas crackers and each tug of each cracker revealing something about each of these characters, even exposing their stark fears and apprehensions, making the reader see each one of them as weak, mediocre but utterly believable as human beings, suddenly confronted with the hideous truth of their natures.

Even Doctor Fischer, the powerful man playing God, in his devilish schemes is revealed to the reader in all his pathos and pain. At the end of the party, he is no longer the Machiavellian host taunting and mocking his guests with barbed insults and jests crueller than those in a story of Hector Hugh Munro, but simply an old, unloved man, quite unable to find any reason for living any longer.

“‘Are you so sure that I want to live? Do you want to live? You didn’t seem to when you took those crackers…Perhaps, when it comes to the point, I have an inclination to live too. Or what am I doing standing here?’

Graham Greene, Doctor Fischer of Geneva

‘You had your fun tonight, anyway,’ I said.

‘Yes, it was better than nothing. Nothing is a bit frightening, Jones.’”

What other book at this age of pompous pretension can convince us more effectively to look beyond the razzle-dazzle of these gala parties, the full-blown pictures in tabloids into the heart of darkness, filled with ghosts of greed, parasitic self-interest, and even loathing, all of which do not even escape our harsh, prejudiced mockery? Doctor Fischer of Geneva makes us look at the mediocre man that lies behind the preening figure that tries and fails at playing God.

“I looked at the body and it had no more insignificance than a dead dog. This, I thought, was the bit of rubbish I had once compared in my mind with Jehovah and Satan.”

Graham Greene, Doctor Fischer of Geneva