Goodish Farce That Could Have Been Great Satire

Mr Shashi Tharoor, where are you?

Of course, I am aware that you still make headlines these days, albeit mostly on these bustling social networks, but most of the time, it’s nothing but some new elaborate, almost unpronounceable and quite devilishly incoherent word that you share with your fervent fanatics who live and swear by your name and the whole of India goes on a bend, either cocking its erudite eyebrows over your sheer cheek or scratching its turbaned head to make some sense of it.

We encourage you to buy books from a local bookstore. If that is not possible, please use the links on the page and support us. Thank you.

Surely, Mr Tharoor, you can do much better than that.

The Great Indian Novel (Viking Press, 1989) was written and published 30 years ago and it is something of a pleasant surprise that even today many consider it as an audaciously original and even subversive moment in Indian post-modern literature. I myself read it about half a dozen years ago, when I was more impressed with Mr. Tharoor’s verbal prowess because he did not play it for thrills, as he seems to be doing today (but then there were other sensationally lurid things that he had been found in the middle of, as well), but rather harnessed it richly and effectively to tell us a lively story.

First of all, the concept has to be admired. Yes, it is very easy to say today, what with a tediously contrived Prakash Jha multi-starrer film modelled on the Mahabharata, that the Indian political battlefield, right from the time when the country earned its freedom to today’s relentless wrangle between the always divergent parties BJP and Congress, can be equated as an eternal and seemingly endless Kurukshetra War, albeit one in which there is no lasting victor.

But back then, when India was just on the brink of the watershed moment of cultural and technological revolution of the 1990s and still stumbling with shadowy malice in its political corridors, to sum up, with crystalline clarity, the very ambiguities and moral duplicities that defined much of the country’s tumultuous political crisis, reaching a head in the 1970s and 80s, in an epic-length parable linked with the myth would be subversive, to say the least.

For even those, who are ignorant of Mr. Tharoor’s said verbal prowess, The Great Indian Novel will prove to be a brilliantly welcome, breathlessly entertaining experience. The book is less self-indulgent than the Bollywood pastiche of Show Business, less preening and desperate to impress than his story collection The Five Dollar Smile and Other Stories and certainly less didactic than Riot. The writer takes us on a whirlwind tour through the very annals of history with almost breezy irreverence, adhering loyally to most of the narrative arc of the epic and ingeniously blending it with everything that the country has faced since the beginning of the 20th century, from the birth of the freedom struggle to its days of both glory and despair, to the acrimonious Partition to the subsequent political limbo right down to the dark days of the Emergency and the resulting fallout, with seamless, superb ease.

And then, there is the devilish, even morbidly saucy wit that accompanies his well-tailored prose, taking the untimely demise of Pandu from the original text and recasting it, with a roving eye, as the dark mythos of the death of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, staging an uproarious scene of burlesque comedy in the lurid boudoirs of Maharaja Hari Singh mere moments before Kashmir is annexed, mixing up Bengalis with Belgians and even referencing Vikram Seth with frequent detours to the phrase, especially in the most crucial moment of the narrative.

The catch

Yes, it is all brilliant, entertaining, and even hard-hitting in equal measure as the writer delivers inarguable conclusions about the very travesty of the country. But for all the fun, this is hardly the subversive satire that it strives to be.

George Orwell’s Animal Farm meshed the bare bones of a fairy tale with subtly cynical digs at the Bolshevik Revolution. Or to hit closer, Salman Rushdie’s novels blended the fabulous with the historical very successfully.

Mr Tharoor, on his part, labours hard to draw his parallels and while the effort pays off in notable strokes, like casting Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru as the well-meaning yet blind-eyed Dhritarashtra or Mohammed Ali Jinnah cast as the promising but overshadowed and misunderstood Karna, many characters misfire because they are mostly self-indulgent attempts at fleshing the iconoclast heroes and villains of the original text with only the quirks of their more recent counterparts.

In The Great Indian Novel, Yudhishtir has to drink urine, Bhishma, renamed as Gangaji, has to fight for the rights of the indigo workers and rally everyone around for freedom and Draupadi has to be a democracy, torn and unrobed and nearly shamed in the political arena of the country; brilliant as these might sound on paper, they are essentially plot points that the writer manipulates and contrives to fit the original epic and even the whole of history into his own scheme. There are, as said before, some well-crafted episodes of comic pathos, like a protest against a British tax on mangoes, the beloved fruit of the country, and Mr Tharoor also makes space to explain, with candour and wit, bank nationalisation or the appeal of the Ambassador car. But every brilliant satire needs also compelling villains and this book only riffs on colonial literature, from General Dyer renamed needlessly as Colonel Rudyard or the British Resident named needlessly after Sir Richard Attenborough, perhaps only because he played the confounded General Outram in Shatranj Ke Khiladi.

That said, even as it tries too hard to subvert its genre, The Great Indian Novel offers more scalding wit and sublime wisdom than that you would normally find in other Indian fiction today. Get entertained and enlightened in equal measure.

Favourite Quote:

We soothe ourselves with the lullabies of our ancient history, our remarkable culture, our inspiring mythology. But our present is so depressing that our rulers can only speak of the intermediate future or the immediate past.

Recommended For: Readers aged between 16 and 60 will both enjoy it a lot and it will be particularly a treat for those who have a very avid interest in both Indian mythology and politics. Those, who have also known and witnessed the major events chronicled in the narrative, will savour Mr Tharoor’s perspective on the same.

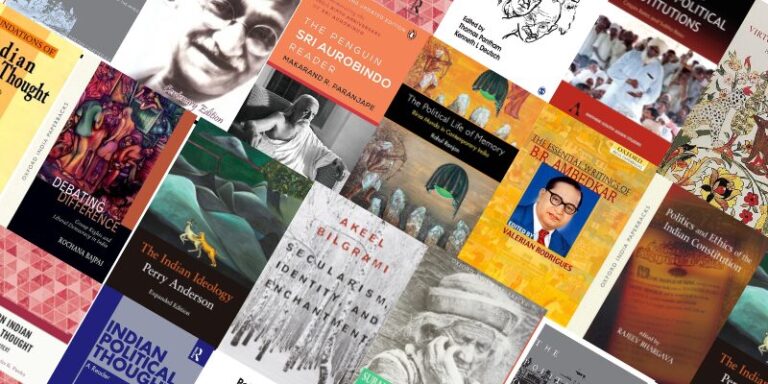

Suggested Reading: Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children covers most of the major incidents of India’s 20th-century political history with more deft and imaginative allegories and has even a fabulous original narrative of magic realism of its own. It is well worth the length of 600+ pages.