Jenny Bhatt is a writer, translator and a book-critic with two acclaimed books out over the last year – Each of Us Killers, that was out in September 2020 and is a story-collection and Ratno Dholi: The Best Stories of Dhumketu, was out in October 2020 and received wide-spread attention fo its exceptional style and also because it’s “the first substantive translation of the Gujarati short story pioneer, Dhumketu“.

Before we speak about Ratno Dholi and translation, I want to talk a little about your equation with Gujarati literature and the language. What are some of the stories you remember reading or listening from your mother? How comfortable were you with reading in Gujarati? Did you have to reacquaint yourself with the practice? Two years ago, I started engaging with fiction in Gujarati and the pace, so laborious after years of not seeing the script, was a big challenge. Did you have these issues? How did you tackle them?

Jenny Bhatt: My mother loved the Gujarati folk tales that she herself had grown up hearing from her parents. So we four sisters and brother grew up hearing these from her. A lot of these have been documented by Jhaverchand Meghani as part of his decades-long pre-Independence project traveling around Gujarat to preserve the oral storytelling traditions that were in the process of disappearing even from rural areas. One of our favorites was about the four stuttering sisters. I did a contemporary, feminist retelling of this in my own collection, Each of Us Killers. It’s titled ‘Journey to a Stepwell’.

I grew up reading Gujarati literature and periodicals at home because, during my childhood, there were really no libraries or non-academic bookstores in Bombay’s eastern suburbs. We had access to some private libraries of school teachers or family friends. That was it.

So my leisure reading was mostly the Gujarati books and weekly magazines (e.g. Chitralekha) that my mother subscribed to. When I left to go to the UK for my engineering degree, my Gujarati reading fell by the wayside. My mother’s letters were always in Gujarati, though, so that helped. Then, she started sending me Gujarati books as gifts and that also helped. When I moved to the US, I found a couple of bookstores in the midwest where I could buy Gujarati books too.

All that said, reading is one thing and translating is entirely another. Translating is a craft, like writing. And it has to be learned either from other translators or through trial and error. In my case, it was the latter.

When I moved back to India in 2014, I lived in Ahmedabad. So, during the 2014-2020 period when I worked on this Dhumketu translation, I was able to re-immerse myself in the language through daily conversation, reading, and even writing voluntarily for a couple of local organizations. All of that helped me get back into the rhythm and flow of the language.

Translation is a cultural exercise, both for the translator and the reader. What was it like to connect with that heritage, especially having lived away from India? Does your mental map/emotional make up as a writer undergo changes as you read Gujarati stories?

Jenny Bhatt: Actually, I feel that I was always more engaged with Gujarati literature despite having lived away from India than many Gujarati people who’ve lived in India. Of course, it’s different when you’re not conversing in the language daily as you do when you’re living in India. I’m pretty sure I would never have taken on a translation project if I hadn’t gone back to India in 2014 to live in Ahmedabad for an extended period of time. That certainly helped my confidence level. But, in terms of cultural knowledge, I’ve always been connected with my heritage.

After my mother, I’m the family historian because I love to collect all the stories and histories of our ancestors and ancestral homes. Similarly, I love to collect Gujarati idioms, phrases, metaphors, etc. What you might call rudhiprayog kahevat.

That said, when you’re translating, you’re immersing yourself differently in the stories and the language than you might when simply reading. You’re interrogating word choices, sentence structure, story structure, and more in both the source and the origin languages. So that definitely changes how you approach your own reading and writing, both intellectually and emotionally. I wrote about this for Poets & Writers last year.

Both your books were published during the pandemic, how did you cope as a translator and writer – were there any specific challenges that you faced – in the process although they were written before?

Jenny Bhatt: People tell you that writing is one thing and publishing is another. And that truth really hit home for me with this pandemic publication of both my books. The entire process of getting these books out there is hard enough without a pandemic — all the promotional stuff, the book events, the interviews, the reviews, the essays to be written, the emails.

But, during a pandemic, all this was harder. There were no more physical book events and bookstores and media venues can only do so much online. Naturally, they’re all going to take on books and writers they think will attract larger audiences. So I think the biggest challenge for most debut writers (the ones who didn’t have big publisher PR engines behind their books) was just getting some visibility for their books.

And then, I had two books come out in September and October in different countries. So the promotional cycles overlapped, but were in different time zones and there weren’t any market synergies that I could take advantage of. I had to promote both books differently to different readers. As a debut writer and debut translator, I could not dictate the timing of my book launches. So I did the best that I could.

One of the things I am most intrigued by is the creative energy it takes to be involved with writing at all times – non-fiction, fiction, teaching it, talking about it. Does it exhaust you, and do you find yourself needing a ‘refill’? Are there are art forms or channels you go to (if) and when the written word gets a lot?

Jenny Bhatt: For me, just focusing on one project is exhausting. I need to take a break from writing or translating one thing so it can breathe and I can come back to it later with a fresh mind. It helps me to have different writing and writing-related projects running simultaneously. Each project feeds into the others. Teaching, translating, and book-reviewing, all make me more mindful of my own reading and writing. And being a close reader and writer helps how I approach teaching, translation, and literary criticism. Each of these kinds of reading or writing fills the well for the others. There are many writers, over the centuries, who have worked and continue to work this way.

I do have other things I like to do when I’m not working with words. I cook, garden, walk, watch movies, spend time with my family. Just normal, everyday stuff. There’s always something to do, isn’t there?

The most important thing, I find, is having an effective time management process. I learned good project management skills during my corporate career when I was managing teams across countries and with multiple projects and deadlines. I’ve carried over those internalized skills to my literary career as well.

You have an incredibly public presence as a writer, with active digital participation. Do you also connect with readers at a personal level through these platforms?

Jenny Bhatt: Oh, there are so many writers who are way better at social media than me. I do have a few personal rules, though. I only engage in literary discourse; I don’t spread negative/toxic energy out there; I try to respond to all who engage with me in meaningful ways (vs trolling); I aim to contribute useful stuff so that people find some value in following and engaging. That’s about it.

So, yes, if you look at my social media, you’ll see that I do respond to all who engage with me meaningfully. I get at least 2-3 emails a week through my website with people asking for advice or just to tell me they enjoyed reading something. I respond to at least 95% of these messages too. In the end, writing is about connection.

But I won’t waste my time or anyone else’s with performance or drama. Let’s save those energies for the actual writing.

Which are some of the Gujarati writers, poets, playwrights that you recommend fellow Gujarati-readers to read, some of your mother’s favourites?

Jenny Bhatt: Oh my goodness. So many terrific Gujarati writers out there. Bindu Bhatt, Dhiruben Patel and Ila Arab Mehta are three of my favorite contemporary women writers. Definitely read Dhumketu, K M Munshi, and Jhaverchand Meghani.

Joseph Macwan was a foremost writer in the Gujarati Dalit literature movement. Rita Kothari has translated one of his novels rather beautifully. I interviewed her about it here.

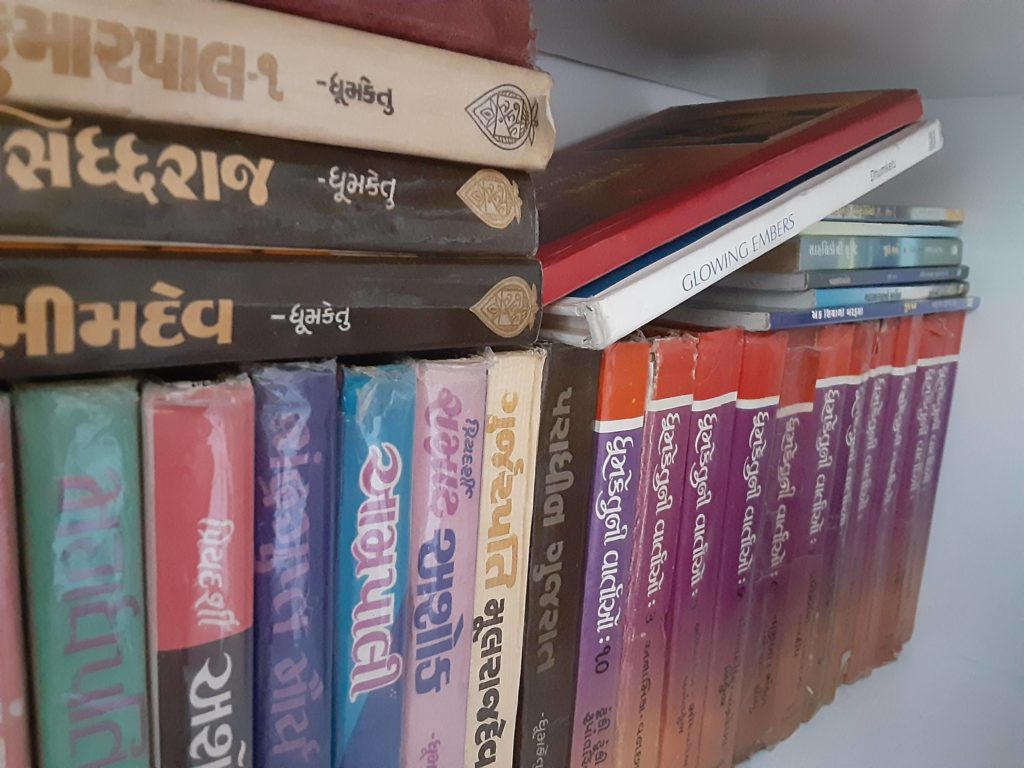

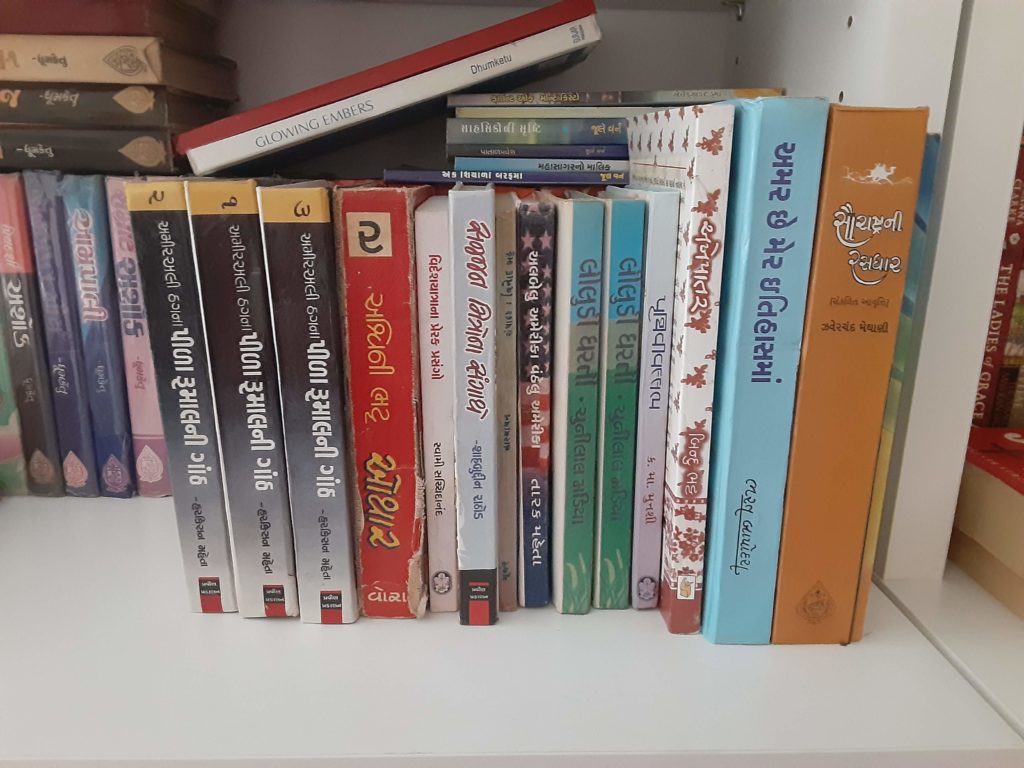

My mother loved Dhumketu’s short stories the most. She had all the volumes. She also loved his historical novels. She was a big fan of Saraswatichandra, the massive three-volume novel by Govardhanram Tripathi. Her set was so badly damaged when I inherited it that I had to discard it and buy a new one. She loved K M Munshi’s Patan Trilogy (translated into English by Rita and Abhijit Kothari) but felt that he put too much “unnecessary masala” into his stories.

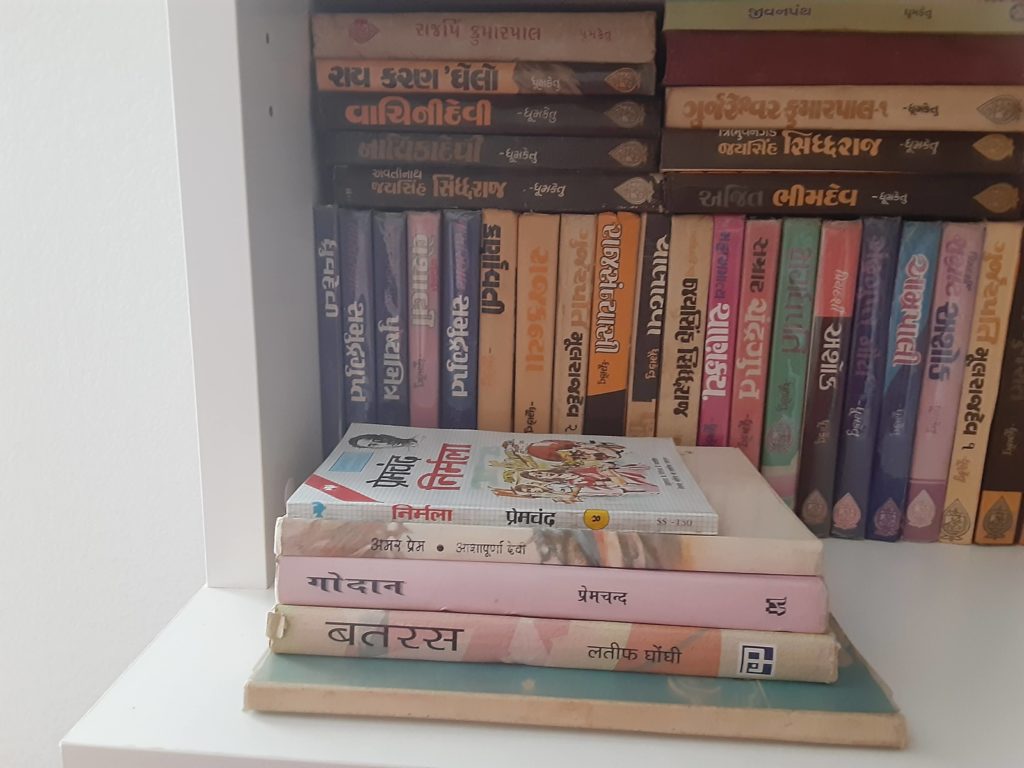

She read Tagore and Premchand in Hindi. She also enjoyed reading western classics in Gujarati translation because her father used to do that: works by Jules Verne, Stefan Zweig, Victor Hugo. In fact, my grandfather had himself translated entire novels by Jules Verne and Alexander Dumas from English to Gujarati but no one other than my mother ever saw them, unfortunately. He earned his living as an accountant on a sugar plantation in Kenya so such literary pursuits were mere hobbies.

With bibliomemoirs, letter collections, and published journals, my favorites are as follows:

— Bibliomemoirs: Reading Lolita in Tehran by Azar Nafisi is my gold standard in this genre for many reasons that I would need an entire essay to cover. Zadie Smith’s essay collections aren’t strictly bibliomemoirs but she often writes so beautifully about the books she’s loved and why.

— Letter collections: Vincent van Gogh’s letters are filled with so much insight about the processes of making and appreciating art; Virginia Woolf’s many letters to friends and family members are almost as good as her published criticism and essays; the letters exchanged between Sylvia Townsend Warner and William Maxwell, her editor, remind me that it’s possible to find such sympatico souls in this industry.

— Journals: I revisit the journals of Virginia Woolf and Susan Sontag often because they remind me that writing is a lifelong journey and a process. These days, I revisit my decades-old journals more often to see how I’ve evolved (or not.)

Are you currently working on something?

Jenny Bhatt: Yes, several projects: a novel, a translation, a book review, another writing workshop. All in various stages of completion.

Rapid Fire

Favourite digital platform: Twitter because that’s where, I believe, the best literary discourse happens.

A non-literary cause you care about.: Adult literacy, for sure. It’s a cause I’ve worked toward in India from my teenage years and continue to support.

A book you have given or been given too often: I don’t think there’s any such book, interestingly. I don’t get books as gifts, sadly. A book that I’ve bought as a gift for others often, on the other hand: A Suitable Boy by Vikram Seth. It’s got everything: the marriage plot, postcolonial India’s many challenges, meandering plot lines; drama and conflict, etc. If someone hasn’t read any Indian novels in English, this is the one book they should read. Yes, it’s of a certain time and class of people and it feels more 19th-century than 20th-century in style but it’s a literary feat of a novel, really.

A movie you liked better than the book: Hmm. That’s a tough one. I’ll stick with Indian movies. As much as I enjoyed R K Narayan’s The Guide, I think the movie version with Dev Anand and Waheeda Rehman is infinitely better. This is where the Bollywood song-and-dance sequences really come into their own. And, despite Dev Anand’s usual melodramatic shtick, he’s convincing in his evolution from conman to god-man. And Rehman, of course, outshines every single person in every single frame.

Disclaimer: This interview was conducted in March 2021

We encourage you to buy the books from your local bookstore as far as possible. If not, please use the links above and support us. Thank you.