I first met Anukrti a few months ago, at the book launch of Latitudes of Longing by Shubhangi Swarup. Purple Pencil Project was then known as onWriting.in, she had just written a book in Hindi (Japani Sarai) and Daura and Bhaunri were both slated for a May 2019 release.

We spoke of peripheries of Hindi readership and literature, and exchanged numbers. Then, months later when she contacted me about the upcoming releases, I did not know what to expect, either of her or her work. But when Harper Collins sent me the books, I was blown away by the subtlety, the layers of her work and because rustic Rajasthan was an entirely new world, a world I at once recognized and did not.

Upadhyay herself is a picture of the same essence that she describes in her books – quiet, powerful and gracious. Currently Mumbai-based, she has a formal education in Hindi literature, business administration and law, and above all, a very interesting background. She has two birth dates, has lived in three cities, is a bilingual writer – the only one, or one of the few known, in India.

Over lunch at her Malabar Hill home, in the cool summer breeze of a May afternoon (a technical fault nearly corrupted the audio recording of the interview, thus the delay), with Vikram Seth’s (her son’s favourite author) books lying around, we spoke about what it is to be a debut author, the Rajasthan she knew and the one she brought to her stories, her love for Japan and much more.

Excerpts:

Tell us a little about your writing journey

My mother says I have been writing since I was five, mainly poetry. I continued writing poetry throughout because my father was very fond of my poems and I wrote mainly for him.

After returning from an eight-year long sojourn in Hong Kong, I penned down a dozen or so short stories, probably because I was trying to cope with a change in my environment, but nothing after that. Then my Papa, a very fine poet himself, passed away in 2017, and I turned to fiction and writing with a new rigour, and reconnected with my literary roots.

And that dedication has sustained. In January this year, she released Japani Sarai, a collection of short stories in Hindi. This year also saw Daura and Bhaunri emerging. And there is already a novel due for release in January, another in Hindi, and then some more.

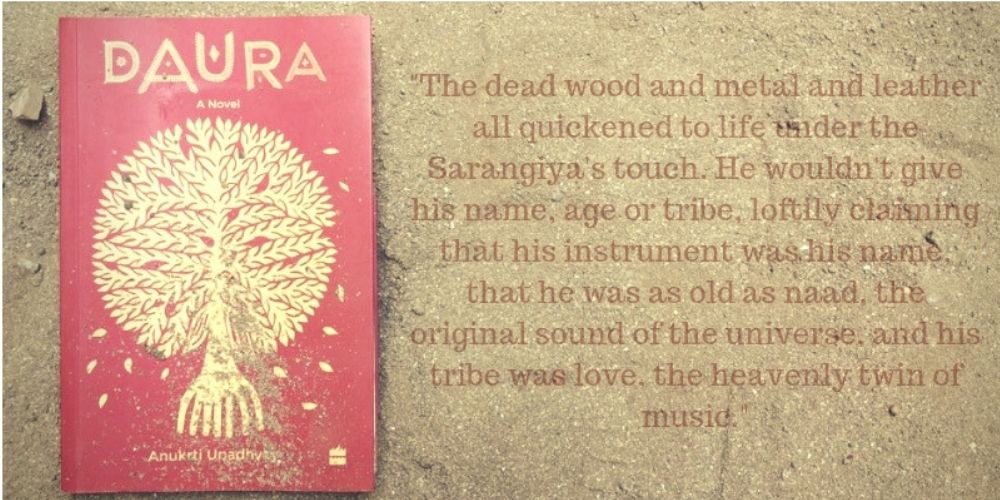

How did Daura happen?

The first draft of Daura happened as a 10,000 word story, a longer short story, and I wrote it all in one flow in August 2016. After I was done writing it, I kept tinkering with it. Then, I happened to meet someone, who knew someone else in publishing.

All I was looking for was some feedback, and the manuscript landed in Rahul’s (Rahul Soni, Senior Commissioning Editor – Literary, at Harper Collins India) inbox. It was just an email, but he responded saying he really loved the book, but “There was something more, something waiting to happen.”

I did not know what it was. It was already over 20,000 words long, the longest I had ever written. After a few months of mulling, I returned to it, editing and slashing things, and suddenly discovered what was waiting to happen. Two chapters – one of the Chief Secretary and the Investigation Report – came as additions after this realisation. That’s when I knew the story was complete.

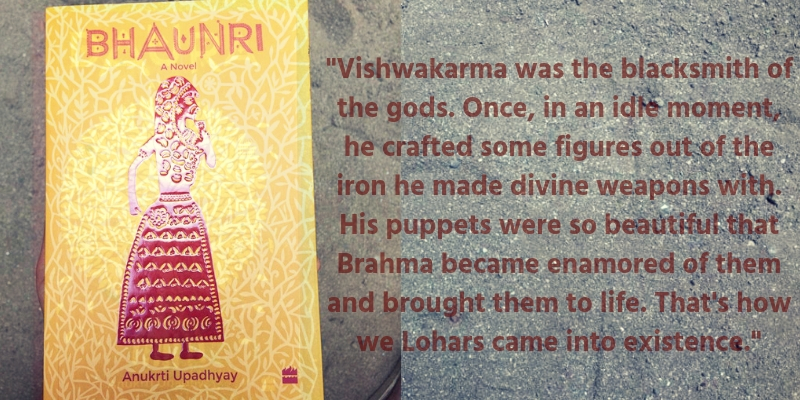

What about Bhaunri?

While I was editing Daura and talking to Rahul, he asked me about my other works. Bhaunri was at the time a first draft and nothing more. When I am writing, the first draft generally happens in a flow of exuberance, and then when I return to it, I see flaws and holes and redo it completely in despair. And I had his advice this time, to help me along.

Bhaunri’s journey to the final draft was a little different. I generally start my stories with an image; for Daura it was the tree (also represented on the cover). Bhaunri began with just the idea of a nomad woman, how they live such hard lives but also have a sense of beauty.

The sun in Rajasthan can be so harsh, but these women, they go about their days with the most colourful ornaments and are still smiling, and I would often wonder – where do they derive their life source from? Even in such a difficult terrain, how they hold on to their sense of beauty?

Here in Mumbai with the amenities of city-life and consumerism everywhere, I still forget to neaten my hair or wear my Kajal. But these women, they celebrate their ideas of beauty each day, whether it is braiding their hair, applying henna, wearing wonderful embroidered clothing, adorning the camels and so much more. Bhaunri was born of the need to find out where the intensity of these women came from.

After that, it was Rahul and my publisher, Udayan Mitra, who saw the books through publication. From the time I first sent out my writing, to strangers on Twitter, to serendipitiously meeting people, I feel fortunate, to have found people who gave generously of their time to read and give me feedback at the early stages of my writing as well.

How much of Daura and Bhaunri are inspired from real-life folktales you’ve heard of?

Fables are all collective imagination; when it was imagined in the past we call them fables; when we imagine it now we call it fiction. When you temper fiction, with mystery or mysticism, it’s resemblance to folk lore increases.

None of the lore I have used in Daura and Bhaunri are ‘real’ folktales; I for one have certainly not heard of a tree princess or a Sarangiya. However the impressions I carried from my mother talking about her own childhood in Shekhawadi, which is an interior part of Rajasthan, closer to the desert, have perhaps influenced Daura and Bhaunri. She would often speak about the characters and lifestyles of the hinterlands.

In that sense, I am indebted to my mother for a lot of my writing. She would talk about the big havelis, playing in the open desert among dunes and even spoke of a man, a figure of fun teased by children, who played sarangi. Maybe that was the origin of the Sarangiya, though in my mother’s stories, he was a jester, not a mysterious musician.

Both the novels are geographically very rich; what sort of research went into that?

I grew up in Jaipur, and we spent some time in Jodhpur and Udaipur, but I have not really traveled a lot within Rajasthan. I have however, encouraged by my parents, read a lot about Rajasthan’s history, both political and natural; my father who was professor of Literature and deeply interested in trees and birds, and my mother as a reteller of her own repertoire of stories, both enriched my inner world.

Then there was the knowledge I gained from reading. Desert’s lore is a presence in old Hindi literature, for example Jayasi’s Padmavat. Rajasthani language itself has a rich folk tradition of its own with songs and stories about the desert and its folk. For instance, the Khejri tree makes an appearance in poetry and tales, it is an integral part of desert lore, their lives, landscape – since it is the only one with green leaves even in the dry season. There’s an old doha that says, if you have 10 khejri trees, 4 goats, 1 free hold camel, you can survive any drought.

So, there was no special research that went while writing Daura. The purpose of the book was not to describe the geography, it was to explore the theme of absolute beauty and how it affects you, and how it affects those that cannot appreciate the beauty but who can escape the Thar’s magic and allure?

Similarly Bhaunri, there is no specific tale that I have heard and anchored the stories to, but the tribes, such as the Gaduliya Lohars, are known to be connected to the King of Mewad, Maharana Pratap. Legend has it that they, the blacksmiths of the king’s armoury, upon the king’s defeat, followed him into a nomadic existence – since the King had lost his land, they vowed not to have a settled abode either.

During my childhood, their covered carts were often parked along the roads, fascinating to my young self. I often wondered what it would be to live that kind of life, to move every so often and not belong anywhere and yet everywhere (and their food smelt so good!)

How do you straddle between being a banker and an artist? Are these two lives not contrasting?

My professional world, as a lawyer and compliance specialist working in an investment bank, has always had the potential to take over life, but I learnt early to keep the two lives separate. I cannot just live for my work, even though I enjoyed it and the energy that was shared by the motivated, driven people I was working with.

I quit only in October last year, so I wrote all three of my books while working, mostly writing at night. It was a private passion and I kept it that way.

But, the cities I lived in, my professional and personal space, they all must have shaped my writing. My father used to say that everything goes into the creative process, but you don’t know in what form it shows, because you have not consciously understood the transformation.

At the end of the day, you as a writer are only translating – other people’s language, their collective experiences, or a collective subconscious.

After the first draft, especially, when you read your work, you can clearly point out the words and experiences you have borrowed. It is not so obvious when you are actually writing.

What sort of feedback have you got from your family?

My mother, who is among the few members of my family to have read my works, is obviously favourably biased. My husband does not read fiction much, and though my son is a reader, he has not read my work.

But the other day, I sat my husband down and told him he must at least hear me read some of Daura, and my son walked in on the reading. He stopped to listen, and then said, “You know what? I didn’t think you would write so well, you write surprisingly well.” A highly patronizing statement which he insists is praise! For the most part though, he thinks I write ‘weird shit’. (Which I assure her, is the highest compliment a teenager can give her!)

Who are your role models, in terms of writers and writing?

I don’t think I have role models but there are innumerable writers I admire. I absolutely marvel at the works of Japanese masters for both their art and the craft, from Akutagawa to Murakami and read and re-read them incessantly. There are many others, too many to name here. One of the most clear and brutal writing is Ernest Hemingway’s. Nothing is superfluous in his writing and he writes everything bare. Everything goes deep and everything hurts when you read his works, he really doesn’t care about your emotions. He doesn’t care about anybody, not even his characters. He writes from a deep place of ego I think.

I think this ego, this arrogant belief in himself is fantastic for a writer. If you have that kind of confidence you won’t second guess yourself, you will be a natural. Everyone can write. Anyone can write. What you need is that confidence. However everyone needs to find their own way, I write because I don’t have that confidence. I struggle.

What’s your next, Kintsugi, about?

Kintsugi is the working title. It’s a story cycle set from Japan to Borneo to Jaipur. Japan is among my favourite places and I have travelled there several times. My Hindi short story collection, Japani Sarai, also have a few stories which were based in the country.

Both the books have eye-catching covers as well. How much of a role did you play with cover design?

My role was limited to knowing what I absolutely did not want – rolling deserts or camels or dancing women. For Daura, I had suggested the Kalpavriksh, since that was the image I had in mind when I began writing it. Our existence depends so much on nature and the tree ti me symbolized nature and its mysteries. The rest of the work was done by the Harpercollins team and the excellent designer, Ishan Khosla, they engaged with. The credit of the vibrant colours, embossed shapes and beautiful lettering goes solely to them.

What’s it like to write in two languages? Can you walk me through that process a little?

The best way to describe it is how Rahul does. He says, “You have these two compartments and you can keep taking things in and out,” and I think I love that.

I definitely think that thinking in two languages and constantly translating from one to other in my head is enriching. For example, my Hindi short stories were first written English. I then re-wrote them in Hindi and was surprised at how they changes substantively and become different, often closer to what I had really wanted to write. Now I am working on translating them back to English and you will see a few of them in an English short story collection.

Which are the Hindi-language writers people should look up to right now?

I don’t read too many contemporary writers, but I grew up reading the classical authors as well as the ones who broke away and created new idioms and styles. Hazari Prasad Dwivedi, Phanishwar Nath Renu, Agyeya, Shriram Shukl, Mohan Rakesh, Pankaj Bisht, Sudha Arora, Anamika, Mannu Bhandari, Mamta Kalia the list is endless.

Would you like your books to be translated?

I am thinking of translating them. I already have been asked to translate Daura, but I want to do it myself so that project will have to wait. There are already a couple of other books in the pipeline and I don’t want to shift focus. It will be interesting to see how translation changes Daura.

2 Responses

we listened interview by anukriti Upadhyaya on 11 th april 2020 n learnt a lot about her experiences in her novel japani sarai.

it was a wonderful educative talk.

we also thank the org rajpal n sons for this beautiful n graceful event.

thanx n congrats .

om sapra delhi

9818180932

She is indeed an eloquent speaker and has a rich bank of stories to share!