Purple Pencil Project spoke to the author of Black Magic Women, Dr. Moushumi Kandali about how she brought the collection together, perceptions of north-east India, her interest in art, the books that inspired her, and more. Excerpts.

How did The Black Magic Women originate? Was it something you read, heard, or saw, that made you want to write this book?

Dr. Moushumi Kandali: Black Magic women happened because I experienced something deeply personal but also witnessed other women and men experiencing the same as well. It was all about a subtle undercurrent of racial as well as socio-cultural Othering of the people from the north-east in the so-called “mainland” of India by a certain section. The entire experience culminated into a tale or fictive narrative through an intense triggering point while reading a colonial report by a British officer about Assam and the Assamese women — where he termed them as seductresses with a low moral values, labelled them as the women who knew Black Magic!

How did its translation come to be? How involved were you in translation process?

Dr. Moushumi Kandali: The translation happened because of the eager initiative of Parbina Rashid who showed great interest in bringing out a collection of my short stories into English. She had previously translated one of my stories for one of her projects. Once we agreed upon the project, we started brainstorming about what we wanted to offer for a larger readership outside the north-eastern region. For me the creative venture was imagined in terms of a direct and definite ‘message’ which hasn’t been widely addressed or delved into deeply so far. I wanted the theme of the translation to be based on a socio-politico-cultural undertone besides being a work of literature and an experimentation in literary craftsmanship as well as creative imagination.

Yes, I was totally involved in the entire process of translation, playing the role of a first reader with critical valuation both as the original writer and a translator myself. I have been engaged in the translation for more than a decade. My English translation of the folk /oral poems of the Miching tribe of Assam titled ‘Listen my Flowerbud’ had been published by National Sahitya Academy, Delhi in 2009, while the Assamese translation of the autobiography of artist Salvador Dali had become a bestseller. With the experiences I could gather in my own personal journey as a translator, I got involved with Parbina’s translation draft and read through every word, phrase or expressions. I might have made her life miserable by my constant comments and feedback hahaha!! But I’m grateful for her immense patience and warm friendship, because of which we could work together so cordially and finish this project.

The book covers several eras too, early 20th century included. Was this conscious? Did you have to research on the position and treatment of Assamese or of people from north-east India in the era? Or were there oral stories you relied on? How much of this is based on personal experiences, if at all?

Dr. Moushumi Kandali: Yes, indeed! It was a conscious attempt to juxtapose and situate narratives through a historical perspective. I believe in the holistic mapping, historicizing, and contextualizing issues at hand so that we can access the reality from various standpoints.

By juxtaposing several eras, I could make a comparative study of how things were back then in relation to what is happening now. Has anything changed, transformed, or evolved? If yes, is it superficial, gradual or otherwise drastic? The narrative references and anecdotes were derived from both oral and written sources, and as I mentioned in my earlier response, some of them were also born out of personal experiences during my stay in Delhi while I was teaching in the SCCE (School of Cultural & Creative Expressions) of Ambedkar University.

The anecdotes I described in the title story of the book are mostly inspired by real-life experiences I had during that time, especially while shifting rental houses from one place to another in several parts of the capital city or travelling in the metro from my house to workplace! In retrospect, I feel grateful that I had such experiences ! It made me see the unseen face of the city and gave me a glimpse of the often unspoken shades of gendered and racial undertones of the metropolis !

Writing about something that could be emotionally disturbing, how did it affect you as a writer? Reading is always a mix of both – hurting and healing. Is it that way for a writer as well?

Dr. Moushumi Kandali: Yes! Writing was the best way to release all the accumulated emotions of angst, anger, sense of alienation, and all other intense feelings. It was indeed a cathartic release though I might sound clichéd. Yes, similar to the experience of reading, the process of writing can equally invite both hurting and healing. I mean hurting in the sense of revisiting a trauma, pricking a wound again which you struggle to bury in the other side of the consciousness.

You have studied art. How much does the visual help the written word and your craft?

Dr. Moushumi Kandali: I believe that studying art has given me different perspective when it comes to creating or weaving a specific idiom of one’s own.

The richness of the artistic/art historical or the visual realm definitely adds a dimension to a writer’s craftsmanship. Understanding the visual allows the literary sensibility to sharpen, as seen in the way the composers of Japanese Haiku paints the world with words or the way authors Umberto Eco or Orhan Pamuk bring forth visuality so poignantly through dense descriptions and thematic exploration in and around the visual components.

Just to give another example, listen to the Sufi rendition of a wonderful literary composition named O Rengreza mere…it talks about a different colour which paints the zigr, the soul, and everything gets colored, even the sleep and the dreams! Such rich poetic imagination and literary experimentation and play with the word Rang and Rangreza speaks volumes about the composer’s deep understanding of the visual realm.

Do you think Assamese writers, or writers from north-east India in general, face a certain representational burden? Of writing and answering all about the region, the culture?

Dr. Moushumi Kandali: Whether it is Assamese writers or the writers from the north-east India, they certainly face a certain representational burden! We are expected to represent and write everything about the region right from politics to culture!

Most importantly, we are very often questioned if we don’t write about the insurgency issue or don’t follow the dominant narrative trope of violence. There is a certain tendency to see things in black and white when it comes to north-east India, for example, either you are pro-state or anti–state , as if there is no in-between-ness or grey areas to talk about. Once I remember, I had read out a story invoking the ritualistic performances of some ethnic community and indigenous group to negotiate the pull of tradition and modernity experienced by a young protagonist. The immediate response was, Where is the political reading in this context? Why is there no mention of the bloodsheds during the days of ‘militancy’ ?

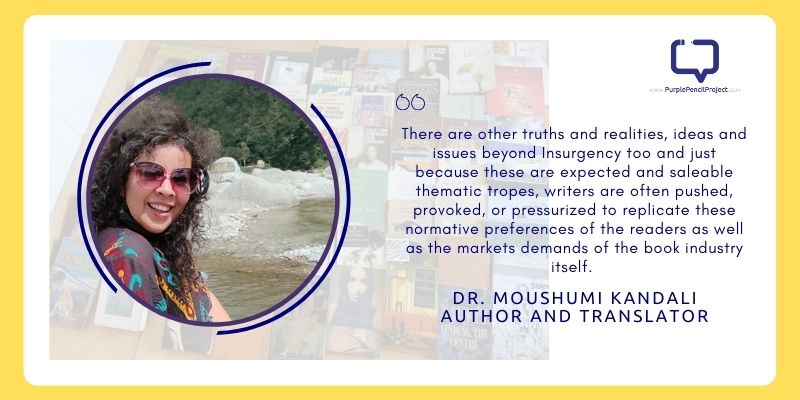

All I am saying that there are other truths and realities, ideas and issues beyond Insurgency too and just because these are expected and saleable thematic tropes, writers are often pushed, provoked, or pressurized to replicate these normative preferences of the readers as well as the markets demands of the book industry itself.

I have always attempted to go beyond this representational burden and have written a wide range of stories which are not location or culture specific at all. They are universally applicable when it comes to issues like contemporary dynamics of the cultural industry and its consumerist spectacles or the issue of surveillance in the post cyber-cultural contemporary life.

Speaking of Moushumi Kandali as a reader – who are the literary influences in your life? Which Assamese authors and storytellers did you grow up reading, and continue to read? What are some books, be it about Assam, the north-east, its struggle, or just pure art, that you would want translated to reach a wider audience?

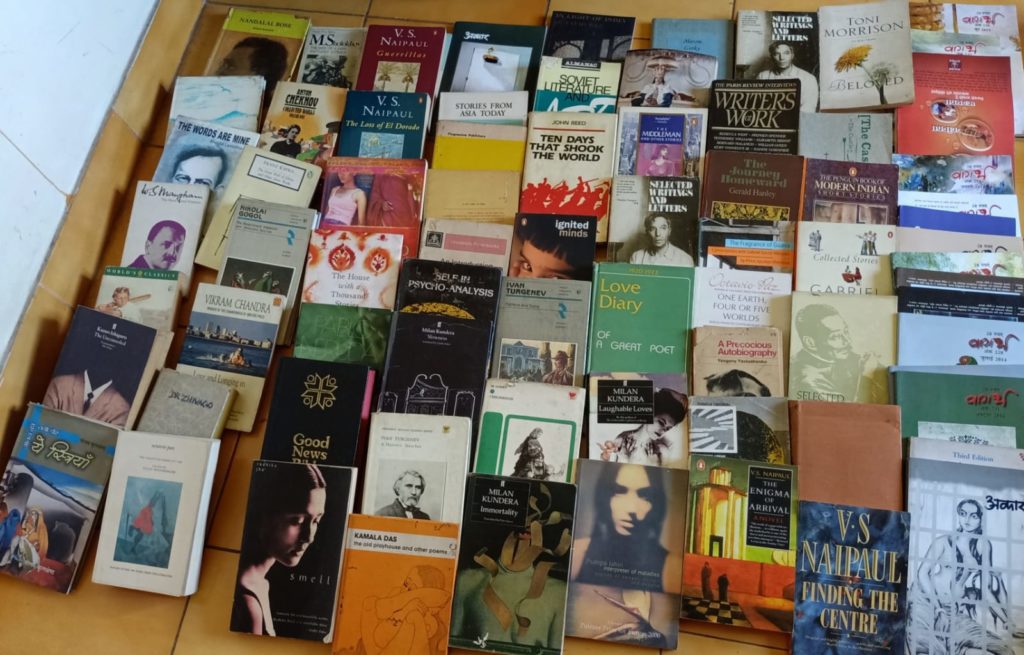

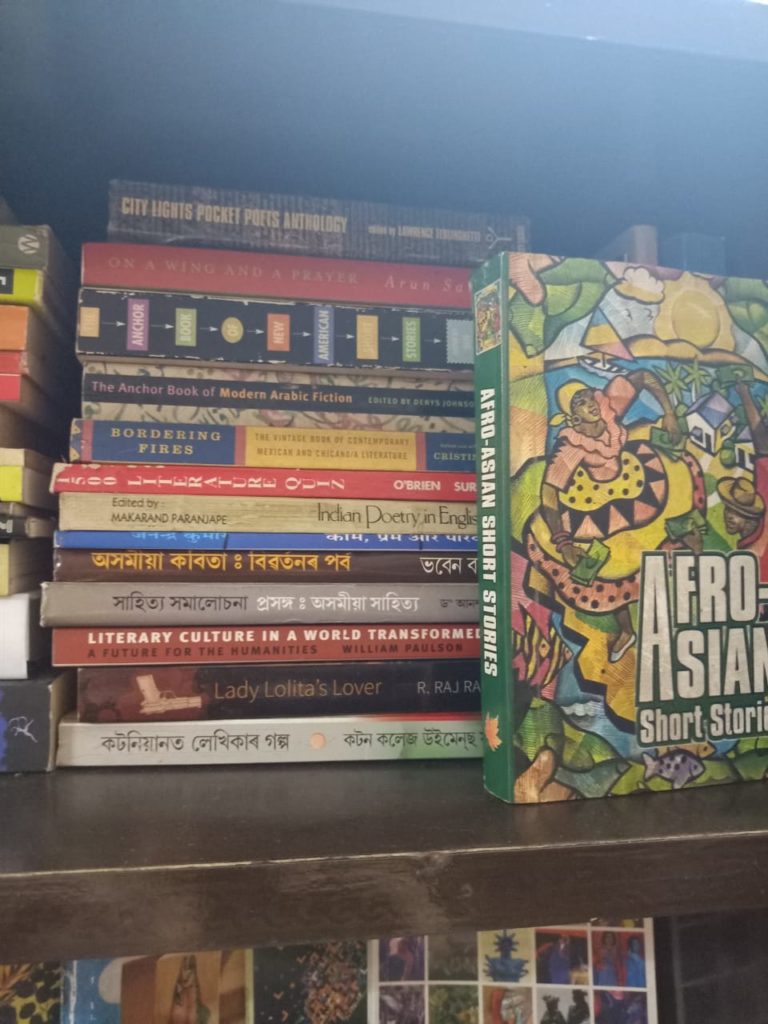

Dr. Moushumi Kandali: I speak read and write four languages and I must say I was really privileged as a child, the daughter of a man who was the principal of a Teacher’s Training Institute which housed a fantastic library in all these four languages!

(Pictures below. Disclaimer, these WILL make you jealous!)

In fact, I learnt Bengali or Bangla because of this library only! Assamese is my mother tongue and I learnt English and Hindi in my school which was a Kendriya Vidyalaya in Diphu. So, I would visit this library almost every day.

I still vividly remember that when I was in class six I came across this English book called Nana by Emile Zola! I read it hiding behind another book as it was for the mature adult readers and referred to the dictionary to understand some words. During that school summer break only I had this amazing experience of reading an experimental Assamese book named Duporiya (Afternoon) by a doyen of Assamese literature, fiction writer Saurabh Kumar Chaliha.

Likewise it was also time to taste Bengali poet Jibonananda Das and his famous anthology named Banalata Sen.Not to forget about the Hindi Poet Muktibodh which kept me engrossed and enthralled though I didn’t understand some symbolic and metaphorical expressions. One day father caught me with these book as he brought the regular Jelpi and Singra (jalebi and samosa, the legendary Indian snacks) which both of us would savour in the library corner.

He said, “Aren’t they something heavy for your age? Ki bujiso nu? Have you understood anything at all?” Nonetheless he said, “Please continue reading even if you don’t understand.”

Looking at the book Nana he said, “Well this would be little too much isn’t it?”

But strange enough he was smiling only! Since then on, I have been reading literature from every part of the world, and India either in original or in translation. From Octavio Paz, Federico Garcia Lorka, to Nirmal Verma, U R Ananthamurty to the Russian master story tellers to the medieval Bhakti poets, I have cherished reading these great minds. The rich vista of oral and folk poems and literary composition of north-east India across different ethnic groups are also worth mentioning here, whether is the cosmological rendition or lullaby, sacred hymns or any songs dedicated to rituals and festivals such as the Bihu songs.

As for the Assamese authors, Saurabha Kumar Chaliha is a mesmerizing experience as he wrote things about the cityscapes in the sixties which are still and more relevant now in contemporary time. I grew up reading the poets more, such as Gyanpith award winner Nilomoni Phukan, Nabakanta Baruah, Ajit Baruah, Bhaben Barua and many others. When it comes to understanding criticism and socio-political analysis in the context of Assam, Dr Hiren Gohain, had definitely been revered scholar .

As for translating some books which I would like to take out to the readers outside Assam or north-east India, are too many! Some of the mentionable are the writings on art criticism by poet Nilomoni Phukan, An important essay on aesthetics by one of the cultural doyen and first Assamese film-maker Jyoti Prashad Agarwala, many more folk and oral poems of the different indigenous people of the region (as mentioned earlier I have already done one book with the Miching tribe of Assam ) and an astonishing early modern Assamese novel called Janggam by Debendra Nath Acharjee which talked about displacement and migration in a very humanist tone and poignant manner decades back much before we started talking this theme since the 1980s !

Another to be added to this genre is Gyanpith award winner Birendra kumar Bhattacharjee’s ‘Kabar aru phool’, which is a very moving account about Bangladesh war and subsequent plight of the people, their struggle and suffering!