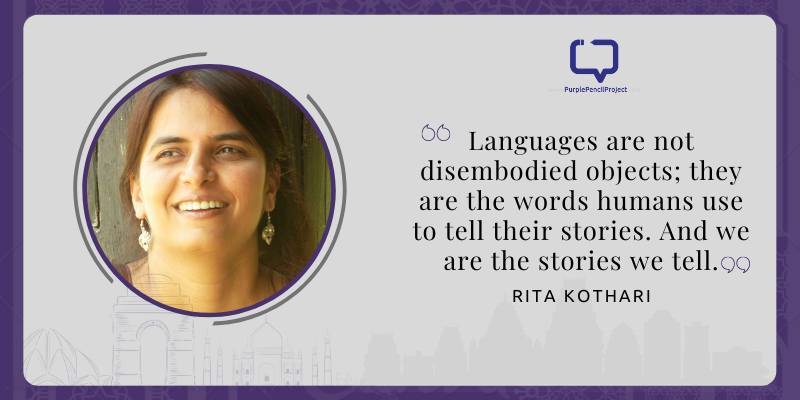

Rita Kothari is a translation theorist, translator, and writer, and a pioneer of bringing the spotlight to Gujarati and Sindhi stories through her work. Purple Pencil Project caught up with her over email to talk about living in a multilingual society, the politics of literature and language, and the digital turn. Read for more.

Your body of work is vast, but is tied by a common thread, that of finding stories and of exploring and probing language. Did your love for stories and words develop simultaneously? Could you talk a little more about it, and about your life as a reader?

Rita Kothari: Languages are not disembodied objects; they are the words humans use to tell their stories. And we are the stories we tell. So in that sense both the story and words are of interest to me. Really speaking, this has more to do with being a listener than a reader. I am told that I used to quietly sit in the room while my father talked to people; or park myself in the kitchen while my mother chatted with someone. Eavesdropping, letting people’s voices, accents, words, inflections fall on my ears is one of my favourite things, and I do it unconsciously. All three get interlocked then – my mediation; the words, and people. You are quite right to pick this up as a common thread.

Language is political – more so in a country and subcontinent like ours – one political identity tying many linguistic ones, and many political identities dividing similar linguistic ones. How do you see your role as a translation theorist and a translator in this context?

Rita Kothari: Translators know that language is political not only on certain days, for instance when it is mobilised to demand a state, a region, an identity. In fact it is at its most political in the everyday.

Why are so many euphemisms used for women’s labour? Why is caste so elliptic among the upper caste and genteel groups? It is to invisibilze things and maintain the status quo; not risk knowledge.

As a translator I let these chinks show, if not in the text, then in the introduction, but quite often even subtly in the text. But more than showing it in the texts I translate, this is a very important part of my pedagogy; to make language accountable for its silences.

Why do we have so many expressions reminding women and Dalits to stay within certain boundaries — words like aukaat, izzat, aabru etc. Such regulations are done in quiet ways; and as a translator I notice them; I pause and think about them. Translation is not only a product, it is a mode of seeing life.

I have noticed that while we grow up hearing more than one language on the streets from neighbours and friends, the digital world only shows us one – English. Our keyboards, our signboards, are all in English. Have you noticed your relationship, your personal relationship, with language change with greater digitization?

Rita Kothari: In fact in my case digitization has made it possible for my family members to use more English than they ever had the courage to. I saw the divisive effects of English much earlier; when my English marked me out from my siblings going to Sindhi medium school. But when I now see my sisters and cousins “like” something on facebook; I feel this is the first time they are participating in my world! The entrenchment of the English language through the digital is very high; but so its democratic expansion. I have always maintained that English is one of the most complex and paradoxical phenomena in India. It is its bondage and liberation, simultaneously.

You have analysed the reading patterns of the urban English-speaking middle class, in your work “Translating India”. What are the significant changes you have seen in these patterns in the 21st Century, as opposed to the period of your study, the late 20th Century?

Rita Kothari: That’s a good question. The book Translating India had a hypothesis that as readers we are likely to gravitate more and more towards English translations of Indian literature. I have not been proven wrong there. However, I also see a lot of bestselling fiction and how-to books being translated into Indian languages (I mean from English). And that is a fascinating trend which I did not see many signs of at that time. My sense is that Hindi and Malalyalam are some of the top languages from India that have a robust translation industry. In the Gujarati language I see constant translations from English; but books only of a particular kind.

Following up from that question, and one that I am personally invested in as I wake up to the loss of my own multilingualism, I want to ask about your linguistic resistances. How did you take your theorist self into your personal life? If you are comfortable sharing – I would love to know how you bring resistance in your personal life, and how do your loved ones respond to it? And how do you navigate the disruption that it might cause?

Rita Kothari: You will have to read my new book for this question! First of all, growing up with a minority language like Sindhi prepares you for a multilingual existence. Since no one speaks your language; and you don’t want to thrust your language on anyone, the Sindhis end up some of the most multilingual people. In the presence of the outside world; or even without them we speak a lot of Hindi. My staple diet during childhood and teenage was Hindi comics and potboilers. As pragmatic people, we pick up the dominant language of the state. Men do it particularly well because they need to conduct business. I picked it up by marrying into a Gujarati family. I spent many years assimilating and not using my Sindhi. But there came a time when I refused to call koki (Sindhi) a kanda na thepla. It would have been more helpful to retain Sindhi, make that much a part of the house if I was not in a joint family. On the other hand, I would not have had the multiple registers of Gujarati that I have had it been a nuclear family. So how do I bring resistance? Let me just say that languages have their dignity, and they hide and shrink if we don’t give them that. I operate from that ethic and am unapologetic about it. So even in an anglicised situation of a workplace or a conference, I see no reason to hide my languages. They are people for me, they deserve respect.

Shifting the focus to literature: There are a few known translators of Gujarati language. I would love to learn from you of lesser known translators and perhaps lesser known translated works that you would love for people to see?

Rita Kothari: I would have liked more readership and notice of the Dalit novel, Angaliyat which I translated (The Stepchild). Its just an important and unusual story. I have the greatest regard for Tridip Suhrud’s translation of Saraswatichandra.

I am incredibly inspired by how you yourself have moved through languages – Sindhi, English, Gujarati. To younger readers, what are some of the ways to reconnect with our other tongues, mother tongues, that seem to have been pushed to the margins in our own consciousness? Some starter packs of Gujarati or Sindhi books for novice readers?

Rita Kothari: I am not the best person to recommend starter packs. Maybe they work, maybe they don’t. But there is certainly much more interest in these questions now than when I began my career. I believe that we need to listen to the language first; the ears have to get used to its cadences. Bhasha pehle ek zazba hai, jo dil main baithta hai. Shabd aa jayenge baad mein.

As a translator and writer, or a creative person engaging with topics that are deeply personal – does that come with its challenges? Are there any practices, processes you have to coping with potential emotional triggers?

Rita Kothari: The triggers remind you that there is a reason why you are doing what you are doing; that its significance is a deeper one. However, the personal is a slippery slope. It is a good place to start and not a good place to end. Especially in the kind of work we are talking about. Also its a practice to know which lessons from the personal have larger ramifications; and which remain too indulgent and narcissistic. It takes some years to get the tone right. I was very inspired by the way Urvashi Butalia handled it in The Other Side of Silence.

I was introduced to even the mention and idea of Indian literature as an MA in English student, where we had a module on the topic. One of the things that I found lacking was portals and ways to discover books in anything outside the anglo american mainstream. Where do you find new books to read? New Hindi, Gujarati, or Sindhi books to read? Bookstores? Libraries? Just searching? What’s your book/story discovery process?

Rita Kothari: Bhasha books have come to me a lot through word of mouth; and then you go about acquiring it from bookstores. There are now great websites for Gujarati, Marathi, Hindi books. Sindhi books I manage to get through friends in India and Pakistan.

Speaking about the industry of translation – how have you seen your role in the publishing industry change? Are there more opportunities, better pay, and overall more respect for translators and translated works, in the wake of the spotlight on it?

Rita Kothari: Certainly more visibility and sometimes better payment too. But the engagement with a translator or translation is very cliched; and that hasn’t changed in these many years. Same set of questions, how do you translate this or that…

In a similar vein, how has academia for a translation theorist changed?

Rita Kothari: I have had a great run as both theorist and practitioner. But the nature of engagement needs to become more robust and intellectual. The perception of translation as a skill dominates these exchanges, and I find the larger epistemological questions of translation constantly sidelined in India.

Finally, congratulations on the completion of your new book. Do we have a definite date on when Uneasy Translations : Language, Self, Experience will be out?

Rita Kothari: Thank you, it should be out by July 2022. This book brings together most of the questions you have asked.

Rapid Fire Questions

The most hilarious Chutneyfied English term you have come across?

Gulzar gave me an example, ye curtainein seedhi kar dein.

A book you think would make for a great Bollywood film?

The Munshi trilogy.

Learn all languages or read all the books of one – a super power yoy’d like to have?

More languages and not all the books in one language, that’s a nightmarish thought!

You have travelled a lot – a city with the most stories?

This is a tough one — Karachi, perhaps, for me especially.