There comes a time in a reader’s life when nothing on the bookshelf inspires her enough to be picked up. Back in the summer of 2016, I found myself facing such a bookshelf in the capital of the southernmost of the northeastern states of India. I had just lost my mother, quit my high-paying, high-stress job and packed up the books (bought by my husband long before I married him) to move with him to Aizawl. In a few weeks, the house was set up, the kitchen was smoothly functional, and I was very much jobless.

I stood looking at the bookshelf. Hearing dead silence from it, I fired up my laptop and opened my favourite blog at the time— Jai Arjun Singh’s Jabberwock. After all these years of scrolling through his book reviews, between drafting legal documents and sending emails, I finally had time to pick up one of his Japanese literature recommendations. I set up the Kindle that my best friend had gifted me a few months ago (but I was too posh for it because of the smell of books and such bish bosh) and made my first e-book purchase (the bookstores in the city back then either had coursebooks or Christian books).

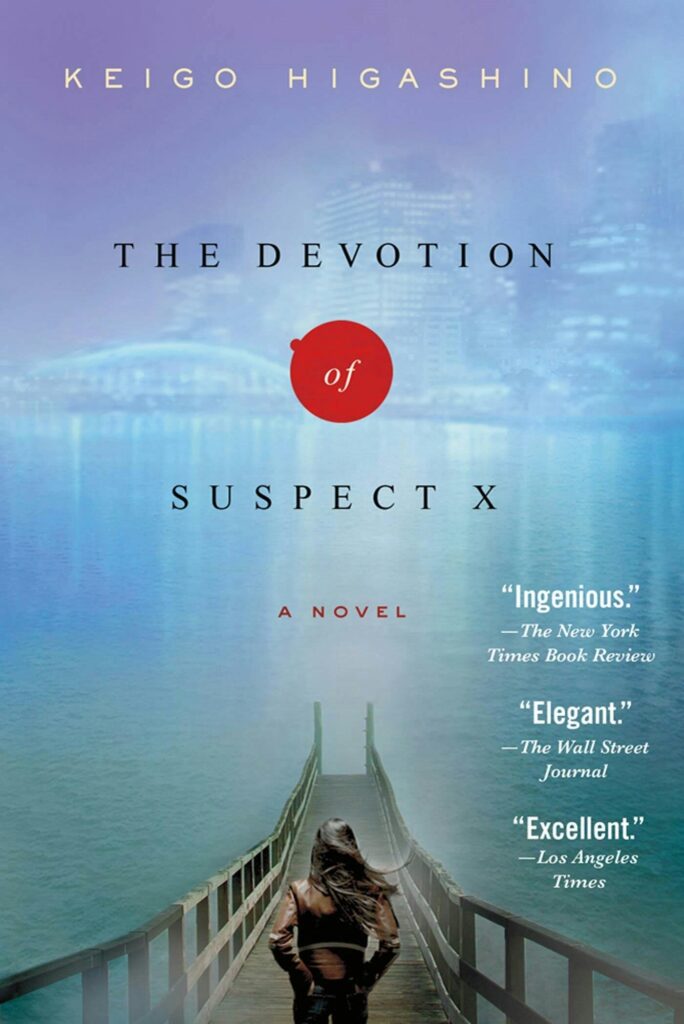

The Devotion to Higashino

This book was The Devotion of Suspect X. If you have not read it yet (or watched the fantastic true-to-book adaptation, Jaane Jaan, on Netflix), it starts with the accidental murder of a husband by his wife and daughter. It proceeds to the elegant and elaborate plan to cover it by their genius mathematician neighbour. There was something about reading a crime fiction novel on my balcony in the evenings when the city was quiet (Aizawl being the quietest city in the country – no one honks there!), and its sky was moody and overly dramatic because of the sun abandoning it.

It provided the right atmosphere for something dark and moody. Kiego Higashino’s spare writing evoked such feelings of isolation and dread, particularly every time my home on the stilts shook from the loud thunder in the otherwise quiet hills. I was hooked. I followed this one up with his equally brilliant Salvation of a Saint and Malice and would have kept going through his bibliography if life did not have other plans.

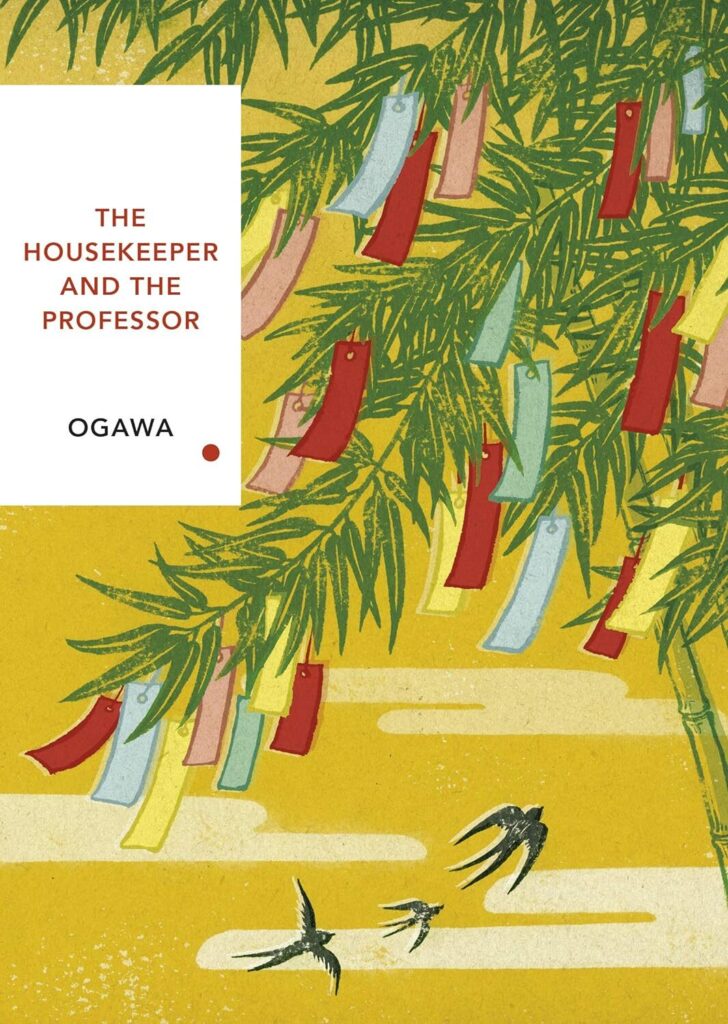

Elegantly Economical Ogawa

Four years on, I had again quit my job to care for my two-year-old and moved to Shillong in the middle of the pandemic. I started a Bookstagram account and discovered a whole new world of translated Japanese literature. By now, I had had a couple of misses with Higashino or simply outgrown him and found a new favourite author—Japanese literature or otherwise—Yoko Ogawa.

The Housekeeper and the Professor came to me riding on a breath of fresh air and dressed in a gorgeous Vintage Classic Japanese Series edition. In this simple and affecting story, a housekeeper is employed by a mathematics professor who is always dressed in a suit. The suit has several notes pinned to it, the most important being, “My memory only lasts eighty minutes.” A seventeen-year-old head injury took away his short-term memory but not his love of numbers and mathematical equations.

Based on conversations about numbers—prime, amiable, triangular, and perfect—a beautiful friendship develops between the professor, his housekeeper, and her son, who the professor fondly calls root because of the shape of his hair. In under two hundred pages, Ogawa wove such a cosy world of human relationships based on mutual respect and little joys, tinged only by the slight sadness that is caused by the inevitability of ageing and death. The elegance and economy of her prose made me crave more of it, and just in time, an English translation of The Memory Police hit the stores.

If our souls are made up of our memories, what happens if parts of our memories are made to disappear? Carrying forward the themes of memory and forgetting, The Memory Police is the story of a woman trying to save a man’s life (or at least his body from physical harm) while he tries to save her soul (her memories). Written way back in 1994, it is a cautionary tale of what could happen if the state is allowed to exert more control over its citizenry and their civil liberties. Orwellian in its scope and Kafkaesque at its heart, this book led me into the weirdly good territory of Japanese literature that the world seems to love.

Of Terrors and Horrors

How does an author paint a picture of the macabre without shedding a drop of blood? When the writer is Ogawa, everyday produce—strawberries, kiwis, carrots, and tomatoes—can be sprinkled with the fairy dust of quiet terror. In Revenge, there are eleven weirdly fantastic individual stories intertwined in a rat king, characters or events of one story making a guest appearance in the next till we come full circle. One story features a dizzying scene of a makeshift warehouse filled with enormous heaps of kiwis. Another has a crop of human-hand-shaped carrots.

Yet another features a woman born with her heart growing outside her chest. There is one about a caretaker of a strange museum of torture and one about a Bengal Tiger! Sort of trippy, Revenge makes for a perfect case to demonstrate the superiority of terror over horror. The garden-variety strawberry, of the colour of blood and shaped like a heart, is ruined for me forever, in the best possible way.

Not every author in Japanese literature shies away from blood, though. My next addition to my Vintage Classic Japanese Series (it has a total of five classics) was the no-holds-barred crime novel Out by Natsuo Kirino. One needs every category of trigger warning before proceeding with this book!

Four women, Yayoi, Masako, Yoshie, and Kumiko, work the night shift at a factory. Within the factory, it is gruelling work, and outside of work, their lives aren’t that great either. Yayoi’s philandering husband has spent all their savings, Yoshie goes back home to her bed-ridden mother-in-law and uncooperative teenage daughter, Kumiko’s taste for the good life has her buried in debt, and Masako, the only one who seems financially comfortable, finds neither her husband, nor her son needing her in their lives.

So when Yayoi ends up strangling her husband one night, she calls Masako, who, for reasons even she doesn’t completely fathom, decides to help dispose of the body—by chopping it up into bits—and also recruits the other two women in the group by offering an incentive or by way of blackmail. The chain of events this sets off is… like watching multiple car crashes in slow-motion.

Recommended Reading: 7 Mystery Novels from Japanese Literature to Keep You on the Edge of Your Seat

Packaged as a crime novel, Out is essentially a commentary on misogyny in Japanese society (not that it is much better anywhere else). There are some very problematic men in this book – husbands, cops, colleagues, etc – and their misogyny justifies every action that the women are forced to take and makes this a very believable story up until the very controversial and unexpected climax. If you can make it past the domestic violence, dismembering, rape, and fat-shaming (of one particular character by the author herself), it is a satisfying story of women breaking bad.

Speaking of misogyny, have you read Murakami?

Missing Cats, Missing Plot, and Murakami

I’m, of course, talking about Haruki Murakami. There is also Ryu Murakami, but kids these days mostly mean Haruki when they say Murakami.

For the sake of my Vintage Classic Japanese Series (bought with my own money, I must specify, because this has started to feel like a paid endorsement), I picked up The Wind Up Bird Chronicle, my first and so far only fictional novel by Murakami. A recurring thought I had while reading it was, “The gentleman doth digress too much.”

Here is the simple synopsis: Toru Okada’s cat goes missing. Then, his wife leaves him and disappears. Then he meets a bunch of strange people. That is when he isn’t at the bottom of a dark well. This book is both intriguing and frustrating because there are six hundred pages of dreamlike writing that go nowhere. Add to that his weird tic of undressing nearly every woman character on the pages of his books. What the.. what!

You know how you endure gruelling childbirth so you can “enjoy” motherhood? The only rationale behind reading such books is to have people much smarter than the author decode the symbolism and ascribe great significance and meaning to his work on Reddit. One Reddit user compared Murakami’s writing style to Jazz: “Jazz is all about harmony and improvisation, and although jazz musicians may deviate from the main melody, they always return.” That’s the thing. I don’t think Murakami ever returns.

I once read about this Japanese method of finding your lost cat: go out and talk to the neighbourhood cats and tell them, “If you see my cat, can you please tell it to come home?” If only Toru Okada had followed the age-old Japanese wisdom, I wouldn’t have had to sit through his book.

Thinking that maybe it’s not him but me, I picked up What I Think About When I Think of Running to better understand him as a writer/person. In this memoir of sorts, Murakami, who has been writing for as long as he’s been running, posits that the two endeavours require the same basic disciplines—focus and endurance. There are no specific insights about the craft of writing or even his process of writing.

But this memoir, styled as a collection of essays about his preparation and experiences and sometimes failures in different marathons, gave me a better sense of the person he is—an ordinary man, sometimes vain, sometimes competitive, sometimes stuck, who has managed to run and write for so many decades because he kept showing up on track and at his desk. For that, respect.

But I haven’t picked up another Murakami since.

Of Death and Other Such Grievances

Why is it that we have so little choice? We live like the lowest worms. Always defeated—defeated we make dinner, we eat, we sleep. Everyone we love is dying. Still to cease living is unacceptable.

– Kitchen by Banana Yoshimoto

The last few years, being “the COVID years”, made most of us deal with grief—both personal and collective—and contemplate our own mortality. Kitchen and its accompanying story, Moonlight Shadow, are beautiful meditations on grief. Both stories have two young people left behind who are trying to come to terms with their personal losses and also comfort each other.

In my personal experience, even as someone who had known loss (the loss of a parent), I found myself ill-equipped to comfort a friend going through a similar grief. This book finally allowed me to formulate some fashion of advice to people who wished to support their grieving friend—a griever needs your friendship but also their space, they need to know they can talk to you whenever they’re ready, and most importantly they need to be fed and provided tea on tap.

I have come this far in my essay with only a passing reference to one of the most important elements in Japanese literature. Forgive me, cat, for I have sinned. Cats are everywhere in Japanese literature and mythology, sometimes symbolising death, other times good fortune. A cat’s perspective is often relied upon in Japanese literature, and the one I loved (I can hardly say I enjoyed it because of the volume of tears I shed) was The Travelling Cat Chronicles by Hiro Arikawa.

A sassy little stray cat is rescued and nursed back to health by a sweet young man called Satoru. He calls it Nana because its tail is hooked in the shape of a seven. After five years of blissful coexistence, due to some unforeseen circumstances, Satoru must find another home for Nana. (No points for guessing said unforeseen circumstances, the very circumstances that will make you weep!) And so the chronicles of their travels begin. I found this book whimsical, witty, poignant and the best pet/human relationship story since Hachikō.

Hoping for a similarly warm and poignant meditation on death, grief and regret, I had recently picked up the first of the bestselling series – Before the Coffee Gets Cold by Toshikazu Kawaguchi. If you’ve made it this far, you know I love Japanese fiction. Yet, sometimes I feel that there is this extreme eccentricity that is being sold to the English-speaking world in the name of Japanese literature—it is either extremely juvenile or extremely violent or occasionally both (like Heaven by Mieko Kawakami!).

Before the Coffee Gets Cold just about managed to giggle like a schoolgirl while trying to philosophise like a high school counsellor. It was superficial and condescending. For me, this coffee was lukewarm, which, in my opinion, is the worst thing for a coffee to be.

The Lives of Women

Moving on, because that’s what the seasons teach us to do, I go back to a time when November had just passed and, with it, the short-lived cherry blossom season in Shillong. (My memories of Shillong are arranged by months, though I seem to forget the years. In my flashbacks are my garden and the flowers in bloom therein, which only tell me the month and not the year.) Missing the cherry blossoms already, I picked up The Makioka Sisters by Junichiro Tanizaki to find these lines: “The ancients waited for cherry blossoms, grieved when they were gone and lamented their passing in countless poems.”

Like the pleasant sorrow of cherry blossoms is the story of the four Makioka sisters and Japan immediately before the Second World War. It is a lament for the old, for the gentle countryside of Kyoto-Osaka region as opposed to the earthquake-ravaged, cold and unpleasantly occidental Tokyo. The same is mirrored in the gentle sister Yukiko of the classical Japanese grace, whose very old-fashioned values make it difficult for her to put herself out there and find a suitable match, versus the younger sister Taeko, a modern, western, financially independent, who is never short of suitors and can barely wait for Yukiko to get married first.

An intimate portrait of Japanese family life, its serialised publication began in 1943. It was also censored by the government, stating, “The novel goes on and on detailing the very thing we are most supposed to be on guard against during this period of wartime emergency: the soft, effeminate and grossly individualistic lives of women.”

I wonder what they would have made of the book I’m currently in the middle of. First published in 1980, Yukio Tsushima’s Woman Running in the Mountains is about a young woman who chooses to have a child outside of wedlock and her struggle as a single mother in the first year of her baby’s life.

In her emphatic introduction to this piece of Japanese literature, Lauren Groff writes, “This may seem familiar to anyone who has known the grind and ecstasy of caring for a small child, the way that time folds in on itself, simultaneously a single endless agonizing moment and a span too swift to capture.”

Its documentation of the drudgery of the domestic qualifies as the very details of the lives of women that the Japanese government would have wanted to shroud under a veil back in the 1940s.

Saved the Best for Last!

One piece of Japanese literature that profoundly affected me (and Martin Scorsese) and stayed with me for days after I had turned the last page was Silence by Shusaku Endo. In Silence, a young Portuguese priest, Father Rodrigues, comes to Japan to find the truth about his mentor, Father Ferreira (who is said to have apostatised) and to seek glory and perhaps martyrdom during his Christian missionary work. Everything that happens in Silence has historical precedence in Japan.

While Japan initially welcomed missionaries and Christianity with a view to gaining trade support, over time, they realised that the rapid growth posed a threat to its internal stability. What followed was a strict nationwide ban on the religion in the 17th century, the execution of missionaries and the persecution of local hidden Christians (Kakure Kirishitan).

What Endo did elegantly and masterfully was frame this story to evoke The Last Supper. To this, he added a layer of nuance, revealing the arrogance, racism and white saviour complex of Father Rodrigues, who only believed in the one truth, a very Western or Abrahamic concept of religion, as opposed to an accepting, inclusive flexibility of eastern religions, which are essentially philosophies. Then came the kicker – doubt, the thing that’s supposed to be the very antithesis of faith. Through Father Rodrigues, Endo asked questions that I have often asked myself—why has God imposed suffering upon humans? Why has he remained silent as his followers are persecuted? Suppose there is no God?

Almost every second page of my copy of this book has been thoroughly underlined, and this book has, in many ways, become my personal Gita, my holy book.

A Bonus Japanese Literature Pick!

Reading Shusaku Endo’s novel Silence in a traditional Kyoto inn, Martin Scorsese noticed how the room and its garden were essentially one. The Japanese didn’t need a Christian God, he realized, because streams and rocks and flowers brought local deities into the house at every moment.

– Pico Iyer, A Beginner’s Guide to Japan

As a bonus read, I present Pico Iyer’s A Beginner’s Guide to Japan, which makes for a wonderful companion piece to reading Japanese literature. Iyer is a travel writer and novelist who is married to a Japanese woman and has been living in Japan for the past three decades. Through his period of living, learning, and unlearning, he made certain observations (and provocations), as a writer is wont to do, about life in Japan, and that is what this book is composed of. It is not a guidebook, nor does it claim to be an authority over Japanese culture and society.

I call this a beginner’s guide not only because it’s aimed at beginners, but mostly because it’s written by one.

– Pico Iyer, A Beginner’s Guide to Japan

Most of the observations and provocations are pithy, arranged into minimalist bullet points, and compartmentalised into different topics, like a bento box. It is also a very (I want to say meditative, but I’ll stick to) calming read, thanks to its classic Japanese aesthetics. And yet, in the name of aesthetics, Iyer doesn’t shy away from shedding light on what is not beautiful about Japan, especially its treatment of women. It is a book full of contradictions, and yet one which may allow the reader to begin to understand life on the little island in the northwest Pacific Ocean.

With that, I conclude my never-ending love affair with Japanese literature, at least for the purposes of this essay. However, in life, the journey continues. Would you care to join me?