Rahul Vishnoi reviews A Gujarat Here, A Gujarat There by Krishna Sobti, translated from Hindi by Daisy Rockwell (published by Penguin Hamish Hamilton, 2019).

The partition novel is a genre unto itself and Daisy Rockwell has seemed to hone her craft on it. Before translating Gitanjali Shree’s Ret Samadhi into Tomb of Sand, which won the International Booker, she had translated Krishna Sobti’s majestic partition-based semi-autobiographical work A Gujarat Here, a Gujarat There.

Recommended Reading: Daisy Rockwell: Translations, the Booker prize and the way ahead

Finding Home Amid Displacement

The story begins in Delhi immediately after the independence. The city is filled to the brim with refugees. All the friends and neighbours of Krishna have already left. Eager to run away from the trauma and chaos that surrounds her, young Krishna applies on a whim to a position at a preschool in the princely state of Sirohi, itself on the cusp of transitioning into the republic of India.

She is greeted on arrival with condescension for her refugee status and treated with sexist disdain by Zutshi Sahib, the man charged with hiring for the position. Krishna fights back. Fortunately, she is offered the post of governess to the child Maharaja Tej Singh Bahadur; she now has a chance to make Sirohi her new home.

Sirohi: A Microcosm of Transition

This story stands at a landmark event in Indian history: it shares itself with the trifecta of Independence, Partition and the accessioning of the princely states by the central Indian government. When a young Krishna gets on a train to Sirohi, she is a half-refugee. Her mind is in turbulence. Her family had lived in Delhi, she was studying in Lahore at the time of Partition, and her ancestral home was in Gujrat, Pakistan.

Sirohi, where she applied for a position, was a small princely state on the border of the states of Gujarat and Rajasthan. At the time the novel begins, in about 1948, there is a struggle underway between the states of Rajasthan and Gujarat to lay claim to Sirohi, which also includes the hill station of Mount Abu.

Recommended Reading: Indian Feminist Literature Through the Ages

When Krishna becomes the governess of Tej Singh, the child Maharaja of Sirohi, she finds herself standing at the site of multiple fissures. She is painted as a symbol of the very land she has come to. She is not only a migrant who’s come from Delhi but also a refugee from Lahore. Now she is in Sirohi and the borders are being drawn between Rajasthan and Gujarat. It’s a chaotic situation since even the legitimacy of the child Maharaja is being questioned.

Krishna is treated as an outsider not just because she is not from Sirohi but also because she is a woman who has left home for employment. The fact that she, too, is a kind of a refugee also adds fuel to the flames.

The Art of Brevity

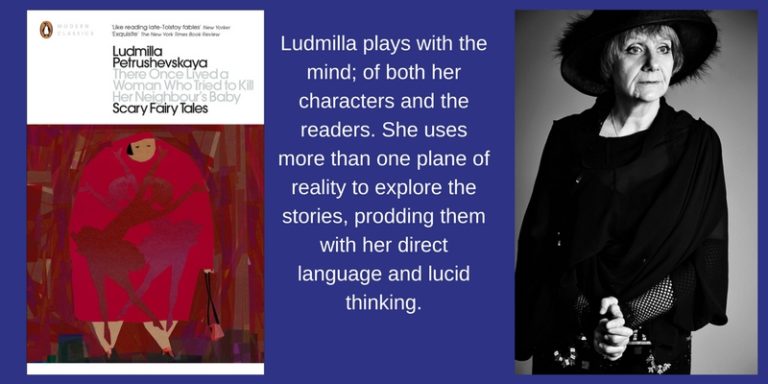

Krishna Sobti’s A Gujarat Here, a Gujarat There is a unique novel in its exploration of the grief and trauma borne out of the partition and tackles the isolation and coming of age of a young governess. As the blurb mentions, it’s a part novel, part memoir and part feminist anthem. It is a testament to the superlative writing capability of Krishna Sobti, whose craft often was at loggerheads with her art.

Recommended Reading: A Comprehensive List of 112 Women Translators in India

In Hindi, this is often mentioned as the war between the ‘shilp’ (the ornamental language) and ‘kathya’ (clean storytelling). For instance, Jaishankar Prasad was the champion of Shilp, but Premchand of Kathya. In the translator’s note, Daisy Rockwell mentions that Krishna Sobti is not here to tell you stories. Yes, Krishna Sobti tells stories—interesting ones, too—in her writing and conversation, but she has an equal, if not greater, interest in language and style.

Sobti is known for her brevity and terse syntax. Where there is a requirement of five words, she will use one. She writes in a very measured tone but not in the sense of holding back something. She weighs her prose, boils down her sentences and then uses only those words that best suit her story. Her prose is full of poems in between, and in some places, this does break the rhythm. Where other authors have spilt buckets of ink writing histories and novels about the Partition, Krishna Sobti, not unlike Manto, attempts to use the smallest amount of words. Although she didn’t suffer from partition violence, her stories are rife with it.

Lastly, a note on translation. Daisy Rockwell has fluidly captured the carefree spirit that Sobti has embodied in this work. Although she, in her translation note, mentions that it is not Krishna Sobti’s intention to make readers understand her writing, Rockwell very clearly has achieved that. She writes that Sobti’s use of language is experimental, and unlike many authors, she is not bothered if you don’t understand what she means or if you cannot entirely follow the story. She is not writing to help you understand; she’s writing to reveal what language can do. In this book, Sobti is more mystic than storyteller, more abstract painter than realist.

Favourite Quote from A Gujarat Here, A Gujarat There by Krishna Sobti

She was walking home quickly when the anxious pond behind Hailey Road warned in a quavering voice, This is no time for taking a walk. Someone might kill you. Understand, little girl. Mondays are very dangerous in Delhi. It was on a Monday that the city of Delhi slipped from the hands of the Mughals. It was on a Monday that the British seized the city too; you do notice what things are like today, don’t you? Go home—this is no afternoon for a stroll!

Conclusion

A Gujarat Here, A Gujarat There by Krishna Sobti is not only a powerful tale of loss and dislocation stemming out from the partition, but it also traces the journey of a young Krishna hell-bent on building a new identity for herself, one on her own terms.

Have you read this tale of displacement, resilience and identity? Share your thoughts with us in the comments below!