Customs, words, culture, language are always in a state of translation; from one audience to another, from one story to another, from one medium to another.

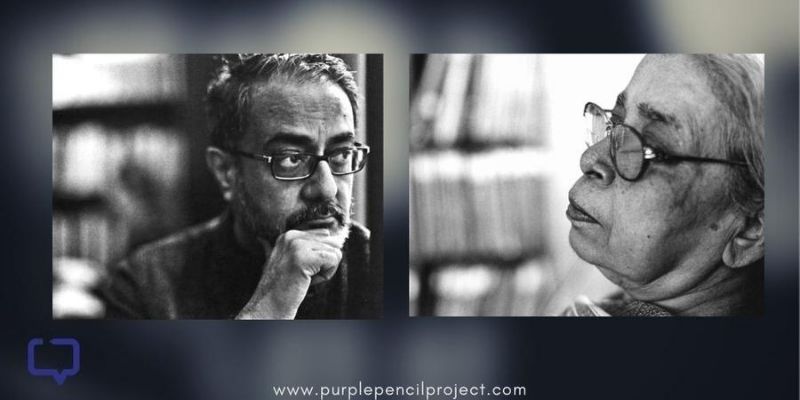

In this conversation between Mahasweta Devi and Naveen Kishore, the celebrated author muses in the words she jots down, the stories that come with those words, and how they make way into her own work.

A meditative long-read, reproduced here with permission from Seagull Books.

Naveen Kishore: When you’re actually sitting down . . . do you see things in pictures? Do you worry about form and content in a certain way? Do you actually get preoccupied with the craft of writing? Do you just let it flow or is it a conscious plan?

Mahasweta Devi: No, no, nothing flows that easily. I have lots of things scribbled down . . . let me see . . . my notebooks are scattered . . . there was a time when I would write down words I came across.

Here, for example.

Parnanar. Made of polash leaves. This refers to a strange ritual. Say a man has died in a train disaster. His body couldn’t be brought home. His relatives then, using straw or other materials . . . the area I speak of is full of the flame of the forest tree . . . the polash. So they use its leaves to make a man.

There’s another extraordinary word. Subhhikshma. You’ve heard of durbhikshma. Or famine. When one describes a year as being subhhikshma, it means there was no crop failure that year. Su means good.

Paap purush. Something out of folk belief. Doomed to eternal life. He keeps vigil over other people’s sins. He appears. Doesn’t appear. He has not sinned himself. But he keeps account of everybody else’s transgressions. Of their paap. Ceaselessly. And so he walks the earth. Taking note of the smallest things. A goat. Punished. Tethered to its post under the blinding sun. Unable to reach water or shade.

Then the paap purush leaves behind his words. ‘That is a crime. What you have done is wrong.’ ‘Tui ja korli tapaap.’

Actually it is not a person. Merely the embodiment of an idea.

NK: Yes I realize that. But just imagine. Say I was entrusted with the job of keeping an account of all the paap. What sort of qualifications would I have? In the sense that, am I taken because I am trusted or because I am being punished? Because it is a very punishing task.

Mahasweta Devi: It might be a punishment. He may have committed some grave crime. Shey hoyto kono paap korechhilo. Some unforgivable sin. And so now, he is doomed to be a paap purush through all eternity.

And in fact, there is never just one paap purush. There are many. Just as there are many places that believe in this.

And there are so many more beautiful words. Bengali words.

Chorat. Meaning planks. Then, dakshankranti. This refers to the Chaitra shankranti. Dak maaney dekey dekey jai. Those selves who are extremely conscientious, vigilant . . . only they can hear this call. Of the old year as it leaves. Questioning. The old year ends today. And the new one begins tomorrow. What have you not done? What have you still left to do? Finish it now.

Thakuri kolai. It is a kind of dal . . . like rajma. It is used only as an offering for the gods. During pujas.

Garbha daan. This is very interesting. A woman is pregnant. Someone promises her that if a daughter is born, she will be given this and this. If a son is born, then something else. Garbha thaktey daan korecchey. The gifting has happened while the child is still in the womb. This legend claims that the unborn child can hear this. And can remember. And record it in its mind. Later, he or she may ask that person about the promise. About thegarbha daanthat is still due.

Our India is so very interesting. Take for instance the Pardhi tribe of Maharashtra. Denotified tribals. Because they are tribals, girl children are in great demand. The husband of a pregnant woman can easily auction off or sell the unborn child.

Pet ki bhaaji. Petey ja aacchey. What’s still in the womb.

Nilam korey dicchey. Auctioning the fruit of the womb.

Then, another word. Jayoti patra. That which is drawn up at birth. The horoscope.

Hell has many names. Narak-er onek gulo naam acchhey. One name which I like in particular is oshi patra bon. There are so many kinds of hell. Oshi means sword. And patra is a kind of plant with sword-like leaves. An entire forest of such plants. And the dead soul must walk through this forest. The sword-like leaves tearing into him. You are in hell, after all, because of your sins. And so your soul must now suffer this agony.

Whenever I come across an interesting word, I write it down. All these notebooks. Koto katha.

So many words, so many sounds . . . I’ve just been collecting them wherever I came across them.

See here, these are the detailed accounts of the expenses of conducting sati. In the early nineteenth century. Think about it. A girl is tied up in a corner of the house. She will be burned. Her husband is dead and now she too will be killed. But the rest of the household is abuzz with activity and excitement.

In the same manner in which they would bustle and plan and arrange for a marriage or any similar celebration. The master of the house is calculating and dictating the costs of this particular celebration. Ghee. To burn along with her. Teen taka. Three rupees. Oronparon bastra. Ek taka. One rupee. That is the cloth to cover her with. The girl is possibly eight years old. Or somewhere around that age.

Sati bastraek joda. A pair of saris. The sari that the sati will wear. There were no blouses or petticoats in those days. Only a sari. The pair amounts to two and a half rupees. Adhai taka. Kath. Wood. Teen taka. Three rupees. The priest will also take three rupees. The sati has to give to the others before she dies. Sati ke daan ditey hoy. That is a rupee. Ek taka. Which means she would distribute in small change. Chaal. Rice. Ek anna. What the price of rice was in those days! Supuri. Du poisha. Betel nuts.

In those days, du poisha was a half of ek anna. Phool. Ek anna. Tokhon to sholo anna ek taka. Sixteen annas made a rupee. The currency of the times. It started from pai. Teen pai-te ek poisha. . . shiki-te ek taka. Dushiki-te ek adhuli.

A shiki is what would be 25 paise today. Or 4 annas of yore. In those days you had a pai. Very small coin. Adhla. Or half of ek poisha. Ek poisha was rather large. Larger than our one rupee coins of today. Like a two rupee coin. Made of copper.

Anyway, to return to the accounts. Korpur. Camphor. For ek anna. Shiddhi. Also for ek anna. This is very important. Shiddhi is bhang. It would be used to intoxicate the girl. Holud. Ek anna. Turmeric, required for all auspicious occasions. Chandan, dhoop, aar narkel. Sandalwood, incense and coconut, shob miliye ek poisha. All together one poisha.

There’s more. Behara. The men who will carry her in the palki, the palanquin. Five annas. Four plus one anna. Dhuli. Those who will beat the drums. Eight annas. And the naptani, she will get—

NK: Naptani? Who was that?

Mahasweta Devi: We have seen such women even in our childhood. Like the barber or napit, she would visit the houses to trim women’s nails, clean their feet, put alta . . . and the tabaldar. . . to play the tabla. Three annas. The total came to fifteen rupees, five annas, three paise. Ponero taka. Paanch anna. Teen poisha. And there you are. There’s a satidaha for you. And your seat in eternal heaven is guaranteed.

Here, I had noted the source. Satidaha, by Kumudnath Mullick.

There are two categories of sati. Sohagun sati and dohagun sati. Sohagunis when the wife is actually with the husband when he dies. Dohagunis when the husband is somewhere else and the news is brought of his death.

So in the Rig Veda it says, imanari raho vidhaba shu patni/ragna eno sharpisha shamprit shantan. This should read samprishantan. ‘Ei shokol nari, boidhobbey klesh bhog kora opekkha, ghrito o anjon lupto—poti ke prapto hoiyya uttam ratna dharon purbak agnimoddhey asray lau.’ Agun. Take shelter in fire. Addressing the widows. Instead of suffering the hardship of widowhood, pour sandalwood paste and ghee on your husband’s body, and then, wearing your finest jewellery, take shelter within the (funereal) fire.

The second part says anasraya anamiva su seva aarohontu janaya joni magne. Hey nari, shongshaarer dikey phiriya cholo. Woman, return to the family.

Gathrothhan koro. Tumi jahar nikat shoyon koritey jaitechho, tini gotashu hoiya giyacchen. He has died.

Choliya aaisho. Come away.

Jini tomar pani grohon koriya garbhadaan koriyachhilen, shei potir patni hoiya jaha kicchu kartabya chhilo, shobi tomaar kora hoyiachhey. Your obligations are over.

Thus, both pro-sati, and anti-sati. You get both in the scriptures. I found this very interesting. I used this in my Amritashanchaya. Just for a page and a half. I have always done fieldwork like this before writing any of my works. Suddenly the thought will strike me. And I will then have to read up something. Or write it a particular way.

NK: It’s beautiful, like listening to folktales. Every word has a tale around it.

Mahasweta Devi: This is also very interesting.

Gandharba bibaher joto shontaan krura karma, mitthabaadi, aar tara dharma o bed birohi hoy. This is anti love marriage. Claiming that the offspring are wily lying heathens.

Niyog karta jokhon shaami, shei chheley kshettraja putra. That means, if the child is by the husband it will be regarded as a kshettraja putra. A legitimate child. A ‘correct’ child.

Nija grihey agyato shwajatiyo dwara utpanno chheley guratpanna. If the child is the result of relations between the wife and some other male relative in the household, such a child is regarded as gurutpanna.

Goponey jaakey utpadon korahoyecchey. One who has been conceived in secret. He’ll never have a proper identity.

NK: Where is this from?

Mahasweta Devi: I don’t have all the sources written down. Can’t remember them all.

NK: But they have been used by you?

Mahasweta Devi: Yes. Somewhere or another. They have come in use. Fitted in.

Ma o baba-r ubhoyer ba ekjoner parityakto putra ke putra roopey grohon korley she hoy apaap pitta putra. Abandoned by either the father or the mother, or by both, he will be called apaap pitta. Blameless.

Kumari kanya gopone shabarna purusher(a man from within her own clan) putra janma dileythat child is called—kaneen. It’s a very common word. I have used it in some of my stories. Kunti had once said, ‘Each of my sons is justified. None of them is kaneen.’ But kaneen was quite an acceptable form.

NK: Acceptable in what way?

Mahasweta Devi: In some places . . . with a feudal system . . . the child of the first night used to be called kaneen. Such sons received a certain respect. The concept was that they were the offspring of the royal family.

Kono kammmatya brahman, shudrar petey shontan utpaadon korley jeebito thekeyo takey shob boley gonona kora hobey.

A child conceived by a brahman out of lust in a low caste woman, is to be regarded as a corpse by his father. That man has no right over the child.

Jodi bidhobar petey baccha koraar jonye kaukey nijukto kora hoto. If someone in particular is appointed to impregnate a widow.

The appointed male had to apply ghee all over his body before going about his task. He was to remain silent. And his job was to produce one male child. He was to fuck her only once. She would be impregnated thus, and overnight, be announced as pregnant. She would therefore be allowed to live. All this would occur within the household. For property reasons.

NK: You’ve used all this in your stories too?

Mahasweta Devi: Yes. In many bits and pieces. So many stories can emerge from these scraps.

NK: The whole process is very interesting.

Mahasweta Devi: And I have to bring in the process.

If the wife gives birth after the death of her husband. Shekhaaney poti golakdhaamey jaabey. That is, the man will go to heaven. But if the husband is alive, aar streer shontaan holo. . . shekhaney ordinary. Nothing special.

Brahman, kshatriya, vaishya, teen barneyi heena jata—that is scheduled caste—ramani garbhey putra utpadan korley shey chheley kintu babar naam pay na. A child born in scheduled caste homes, fathered by brahman, kshatriya or vaishya males, do not get to avail of their father’s names, titles, or castes.

These are vessels and utensils of long ago. Bashon. Bogno. A flat dekchi. Of my mother’s time or even in my childhood. Made of bell metal. Round. Now you may get them in steel. Larger. To cook rice in.

Jambaati. A large bowl.

Baily. A small something to put vegetables in.

Kanshi. Like this, but made out of bell metal. To pour the fish curry into.

Paonli. A sweet word. My mother drank water out of a paonlighoti. A small ghoti. My mother never used a glass.

Chumkirghati. Made out of copper or bell metal. With little round sequin-like things stuck on them.

Chunnunibati. Small bowl to put chandanin.

Patil. A cooking vessel. Kind of handi.

Deg. It’s something that we still use.

Beri. Something like a sharanshi, tongs. Used to remove the handifrom the fire. Dao. Large bonti. Used to cut vegetables while sitting on the floor. Even to cut fish.

See here, these are the details of ‘Shesh Shamanin’, a story I had written. About the last shaman in the saora tribe. The child’s grandmother tells stories to the unborn child. That is what a shamanin does, is supposed to do.

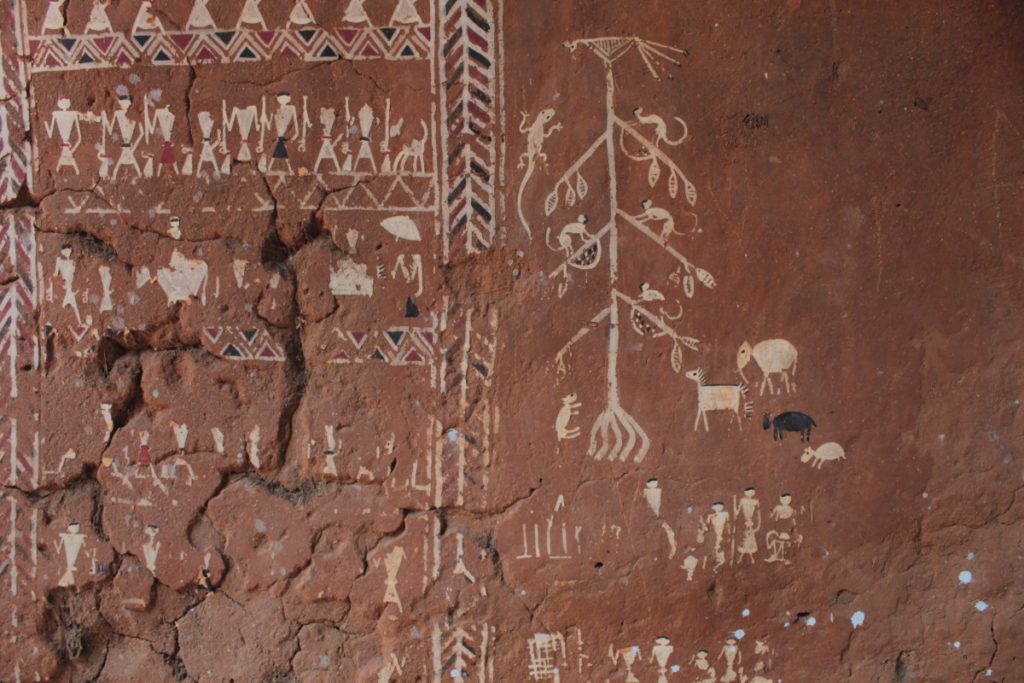

She tells it about ittalan which is a painting but is also god. The form of ittalan no longer exists among the saoras. But among the rathoa bhils, they have pithoro paintings which are ceremoniously and traditionally painted all over the walls.

The area in front of it is supposed to be very sacred. Say you are about to sow your crop. You will place the seeds on the floor. In that space. Before you sow your crop. Your first crop you will place there too. Very few persons are entitled to paint these. The saoras are among those tribes where painting is religion. It’s very interesting. These are the eastern zone saoras. And those are of the western zone. The rathoas. It is painting. But it is also god.

NK: But isn’t that an interesting concept? That painting is bringing god into existence. That the painter is actually painting god.

Mahasweta Devi: And what is most interesting about the pithoro paintings is the predominance of the horse. It’s a lot like the dang pictures which are made into blocks and printed on bedcovers. The entire life is depicted. The gods who are drawn, are supposed to communicate through the painter.

NK: Almost like a medium...

Mahasweta Devi: Yes. All these things are very interesting about the saoras. These spirits are called soom. The paharisoom. Then there are the sahib sooms also. For there were foreigners there, then. Suddenly, the painter is painting a cycle. A horse. The owner of the house points and silently queries the drawing. The painter says it is the need of the sooms. It is what they have asked for. If they can ride horses so can we. If the foreigners can ride cycles, so can we.

NK: So these are demands made by the spirits while the picture is being painted?

Mahasweta Devi: Yes. They can have policemen too. The dailyness of creation. Depicted with explosive joy. Children playing. Women fetching water. A group singing and dancing. Others going off on a hunt.

NK: A lot to do with celebration. Happiness.

Mahasweta Devi: In the case of both the saoras—the eastern and the western lot—there is no greater joy than the daily joys of life. That is the greatest joy. This festival carries on eternally.

I write here about the girl who is still an unborn child. Her nani had told her while she was still in the womb. Which ittalan to draw to appease which soom.

NK: A conversation . . . communcating with the unborn child.

Mahasweta Devi: And the child in the womb understood every word. And remembered. The story goes like this. The child is born. She heard the story in her childhood. About how the saoras were forced to leave their village. She pleaded with her shamanin—her grandmother—to draw an ittalan. To drive away the outsiders. The saoras were peace-loving people. This is a fantastic description. An immense wall. Splashed with paintings. In the Orissa hills. But by the time it is completed, the outsiders have entered.

And what has been the final outcome? Those motifs are now block-printed on bedcovers. Saris. Curtains.

But the saoras had prayed there before they left their village. For a long time it remained theirs. After they left, their flowers still lie, strewn before the wall. The chickens they had sacrificed, their blood still splashed on the wall. The outsiders did not try to protect that place but nonetheless stayed in awe of it. It is something that inspires fear. And gradually it crumbled to ruins.

The old woman who had told her all this is forgetting, now. Everyone has now become contracted labour. She suddenly gets up and tells the girl that she had a dream. That the outsiders were driving away all the sooms. Now that she has had that dream, she is forced to draw. There are no shamanins left. Everyone has gone away. Then the girl says that she will do it.

NK: The one who heard the story in the womb?

Mahasweta Devi: Yes, yes. So she begins to wash and plaster the wall. Using red earth. Pounds rice. Says, ‘Dadi, to what god?’

The old woman says, ‘Child, all the gods are spirits now. I have to provide them with courage, draw separate houses. So that they can stay there. But what to offer? There’s only bad rice, country liquor.’

Then the granddaughter asks, ‘Are they demanding?’

Dadi replies, ‘No the gods too are about to die.’ With the final depiction of the hill on top of which these two will stay, Dadi instructs ‘Sacrifice the last hen.’

‘I will. I’ll draw the ittalan.’ She calls upon her tutelage and ancestors and the sooms. ‘See, this is the last act I do, so do not take away the dreams from me.’

The gods’ house is high. A ladder for the gods to climb up. Surrounding saoras guarding them.

And finally, after so many years, the place becomes a bazaar. The wall is seen as a marketable curio but they could not demolish it due to the vehement opposition of the people; it became the temple of all sooms or gods. Thus it stayed till a big man came and photographed it in detail and carried it to the mills where they block-printed the designs. And minted money.

And this place was called shakal shumera gruha. The house of all sooms. All the gods have a place there.

Now an alley of liquor shops is known shumera gali. After painting, the shamanindies. Before dying she tells the girl the details of the ittalan. This whole story is beautiful.

NK: Tell me more. What are these jottings about?

Mahasweta Devi: About the market within a jail. In 1993. This was when we were trying to release the women.

Rice, two rupees a kg, masur dal, six rupees a kg, eggs, three for two rupees, costliest fish, 20 rupees a kg, meat at 12 rupees a kg, mustard oil 10 rupees a kg, double-toned milk from the Haringhata dairy, half a litre for two rupees, sugar at eight rupees per kg, tea, 10 rupees per kg, and biscuits, 100 gm for Rs 2.

This was purchased for lifers and under-trial prisoners, sold at the above prices to the jail sepoys. They would either send the supplies home to their families or sell them off and pocket the profits. The under-trial prisoners and lifers have no chance of getting these commodities at these prices or in these quantities. I got this information when I was visiting the jails. We cooked according to the quantities prescribed and then showed it to the prisoners. Then we asked them if they got that much. Never!

Then, this buro angul. The thumb. Cut off in the case of Ekalavya. By way of gurudakshina. Details are provided about this. Ekalavya. A bisheshan. Adjective. Lavya means chheda. Sliced off.

Take the word Drona. Purush. This is the origin—utpotti. This is Sanskrit grammar, tika.

One of the meanings of drona is dogdho—scorched. The raven or dar kak is also called dron. So is the scorpion or the brishchik.

And the chatusshotodhonu, a kind of bow, is also called dron.

Dron also means brihatjolashoy, a vast waterbody.

Megher nayak or meghbishesh. When the rain clouds appear, there is always one cloud leading them. That too is known as dron. And when that cloud appears, a good crop is foretold.

Dron also means the acharyaor chief of the Dhanurveda. The book of archery.

Dron also means mountain.

Also a utensil to measure the crop. A limit. I may say, I will give you one dron of crop. Or grain. So a unit of measurement. In the table of land measures, it is equal to 16 kanees. That too was a land measure. Like bighas and kathas. Kanee was applicable not to homestead land but to agricultural land.

Dron kheera is the name of a fruit.

Also, 32 seers of cow’s milk boiled down into kheer will give you dron kheer.

So dron is associated with might and power, milk, food and so many many things. I’m greatly fascinated by such things.

NK: Why do you find this interesting? People ask me such questions about my photographs also. Yesterday I was walking along Camac Street. The drizzle. I was looking down to protect my spectacles. And whatever I was seeing on the road, I could see either in vertical or horizontal frames. A leaf. A stone. If you make them still, they become frames. When they become still, then I am able to explain what I find interesting and why. But I cannot explain otherwise. It’s like taking what I can with my eyes closed.

Mahasweta Devi: It’s maddeningly fascinating.

I’ll tell you about the Kolhati tribe of Maharashtra. I wrote a story about them, ‘Jhuku Jhuku Railgadi’. Jhuku jhuku railgadi aa gila re.

In the kolhati tribe, the first girl child is not married off. This is also the custom in the dombari tribe, on the borders of Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka. The dombaris have a tradition of ceremoniously and officially marrying off their first daughter to Venkateshwar Shiva. After that marriage, the father and uncles and brothers build her a hut adjacent to their home and she begins to prostitute openly. She has to give her parents all her earnings. But such women are not hated by the community. When they walk into public spaces like the market, for instance, people tend to fawn over them. For they are the Venkateshani. They are the wives of Shiva. This goes on and on. But when she can no longer sell her body, she is provided with a hut in a far off spot, and then she is free to entertain any and every man who seeks her services. She has to survive in whatever way she can.

This is a time-honoured custom in those parts. It struck me as extremely peculiar. This happens in Telengana, where the famous Telengana battle was fought, where the people’s war is still being waged. I realized that the women’s side of it has never been heard. Never been considered. We read that book called Women of Telengana which Suzy Tharu and K. Lalitha edited . . . There they mention how these women are used afterwards.

In Maharashtra. The Kolhati tribe. Kishore Shantabai Kaley, author of the book Against Odds, has written of this feature of the kolhatis. Chheda nahi utaarne ka. That means the first female child will sport bangles from childhood. Then one day her father, the panchayat pradhanand others will come and auction her. To the highest bidder.

NK: At what age?

Mahasweta Devi: As soon as she attains puberty. The man who buys her will be the one to first take off her bangles. He will have paid five thousand or ten thousand to her father. This custom is present among the kolhatis, the dombaris. These girls are also those who participate in the local tamasha, their form of rural theatre. Maharashtra has the highest number of kolhatis.

This girl’s name is Manda Hiraman. Her parents auction her for the first time. She gets pregnant. After her son is born, she no longer has any claim on him so she must leave. Then she is auctioned for the second time. Another son. Walks away again. The more sons she delivers, the more her price goes up. People come to know that she delivers male children.

The third time, what Manda did was . . . I met Manda. Went to her house. Talked to her. The third time, at the auction, Manda was carrying a vicious whip. She held onto it. In secret. A whip that could slash the skin. Her father, the pradhan, the so-called client, all the men were there before her. Her mother also. When money matters were being discussed and haggled over . . . By then Lakshman Gaekwad [well-known tribal writer and social activist] had built his organization . . . there were branch offices here and there . . . Manda pulled out her whip and lashed out at all those around her. And then, running out, she climbed onto a cycle and fled to one of those branch offices of Lakshman.

In the mean while, a huge panchayat had met and begun its session. A terrible scandal. That a kolhati girl should act this way. They decided to burn her with tejaab. Acid. That was the ultimate punishment. And hang her upside down. That is, they would insult her as much as possible. Lakshman enters with Manda and says that from now on, she is the superintendent of all the social work in that entire area. ‘Anyone touches her and they’ll have to deal with me.’ Then all her former clients were brought before them. Money was wormed out of them. The father who had collected a neat stash of his own was also made to pay up. And then Manda was provided with a two-storeyed wooden house in far off Jamkheda. The ground floor had a stage and Manda lived upstairs.

And now that Manda had money of her own . . . these people have a tradition of worshipping the Tuljamata. Also known as Bhabani. (She was worshipped by Shivaji too.) Every year her puja is auctioned. If you bid the highest, then all the offerings that come to the temple are yours. Manda took over that puja. Not only did she take it over, but built a temple for Bhabani right next to her own house.

And then she said, speaking in her husky voice, ‘Amma, everyone who despised me, they all have to come here now. They have to pay here now. And whatever they offer in puja, I’ll get.’ And the people in question were quite enraged about it.

Then Manda purchased a Bullet motorcycle. And riding that motorcycle, brandishing her whip, she rides all over the place, keeping a vigil on the rest of the people.

NK: What does she wear?

Mahasweta Devi: The sari in the way that the Maharashtrians wear it. With pleats like the dhoti. Very womanly. Smiles. Speaks in a low voice. Not loud. Her voice is very husky. Manda managed to get many other kolhati girls to her temple. ‘Why do you wait here to be auctioned? Come to me.’

So this group of 16-17 girls would perform their traditional tamasha but weave in these themes. Bring in these issues through dance and song. And the clients are told strictly that they are merely paying for their tickets. They are to watch the performance and then make themselves scarce. The whip hangs near the door. One wrong move and you know what Manda will do to you. She’s a terror.

NK: How old is she now?

Mahasweta Devi: About 30, 32. She told me . . . when I asked her, ‘You are so young but you have two sons? Where are they?’ She replied that she had sent her boys off to boarding school. And yet when I told her, go talk to the people in your maikey, your maternal home, she said, ‘Oh no, I couldn’t.’

NK: There’s no question of her having a sasur badi, I guess. No in-laws.

Mahasweta Devi: No question of it, she’s never been married! She feasted me on puranpuri, which is a luxury, and bhakri, their usual bread. Wonderful! They have a custom among the kolhatis in Maharashtra, that if an unmarried girl has a child, and if she dies, the child gets an LIC benefit, from Life Insurance Corporation. There’s just no end to this kind of interesting stuff. Life is very interesting, isn’t it?

I have lots of notes and scribbles here, as you can see. Marathi lullabies, songs, lines . . .

NK: These are notes to yourself?

Mahasweta Devi: My writing process is anything but haphazard. Before I write, I think a lot, mull over it, till it forms a crystal-clear hard core in my brain. I do all the homework I need to do. Take notes, talk to people. Find out. Then I start expanding it. After that I don’t face any hitches, by then the story is in my grip. When I write, all my reading, memories, direct experience, acquired information, come into it.

Wherever I go, I jot down things . . . the mind remains alive . . . and I forget things too. I’m actually very happy with life. I don’t owe anything to anyone, I don’t abide by any rules laid down by the society, I do what I want to, go wherever I want to, write down whatever I like, roam around . . . but when I come back to Calcutta I feel claustrophobic. Anyway, life has been very much worth living.

NK: Good. Now give me one last strange word, to leave with.

Mahasweta Devi: Let’s see . . . I’m telling you a theme I’m going to write on when I have time, leisurely. I’ve been thinking about this for a long time. The only way to counter globalization . . . just a plot of land in some central place, keep it covered in grass, let there be a single tree, even a wild tree. Let your son’s tricycle lie there. Let some poor child come and play, let a bird come and use the tree . . . small things. Small dreams. After all, you have your own small dreams, don’t you? Like you were saying, as you walk, you see strange frames. Rainwater pooled on the street, a leaf floating there . . .

People do not have eyes to see. All my life I have been seeing small people and their small dreams. I feel as if they wanted to lock up all the dreams, but somehow some dreams have escaped. A jailbreak of dreams. Durga, watching the train [in the novel, Pather Panchali].

An old woman who simply craves sleep. An old pensioner who finally gets his pension. The people evicted from the forests, where will they go? Common people, and their common dreams. Like the Naxalites. Their crime—they dared to dream. Why shouldn’t they be allowed even to dream?

Naveen Kishore is the publisher at Seagull Books.

For the titles of Mahasweta Devi, we encourage you to buy the book if you can find it at your local bookstore. If you cannot, please use this link to order from Amazon, and support us.