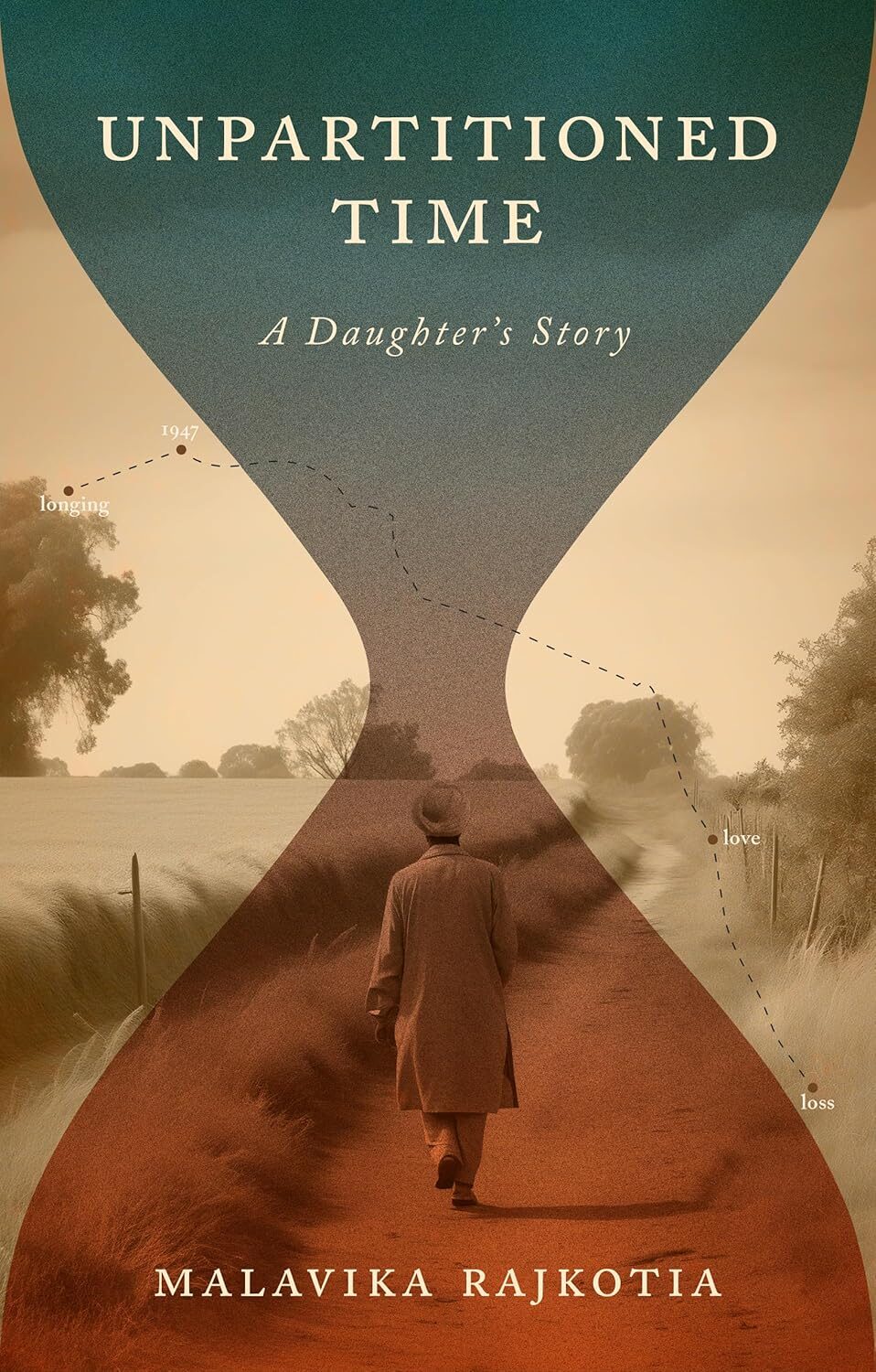

Elsa Mathews reviews Unpartitioned Time: A Daughter’s Story by Malavika Rajkotia (published by Speaking Tiger, 2024).

Dead men tell no tales. It is the living who carry within them the pain, the horrors, the loss, the longings, the stories, and the trauma of a tragedy. The Partition of India led to one of the largest migrations of humanity in history. Not to mention the violence, rape, torture and plunder, massacres and killings that accompanied it, the horrors of which have been much represented in literature and film.

Recommended Reading: Partition Literature: Books You Must Read

For refugees who managed to make it to the other side, it was all about rebuilding life and putting themselves back together for their families, notwithstanding the crushing pain that broke them. Unpartitioned Time: A Daughter’s Story by Malavika Rajkotia is one such chronicle of a family that picked up the pieces after having crossed the frontier, their ultimate submission to their destiny manifested in the figure of Rajkotia’s father, Jitender Singh, a.k.a. Jindo.

A Father’s Wit and the Weight of Loss

The book begins with the death of Jindo, Rajkotia’s calmly eccentric father, whom she compares to Oblamov, the protagonist of Russian writer Ivan Goncharov’s eponymous novel, first published in 1857, who, throughout the book, rarely leaves his bed. Over the years, Jindo justified his languorous existence with good humour and wit. For example, when his wife Darshan asked him one day, “What is your ailment?” “Aaram”, he replied.

However, Jindo gave in to indolence only towards the end of his life. Having arrived on his allotted piece of land in Karnal after partition at the age of 16 and clearing bureaucratic hurdles, he began to cultivate it. It was arid, but young Jindo, recently torn away from his own land, threw himself into nurturing it.

Comforts and Sorrows: The Next Generation

The only thing that had become familiar to my father was the weight of his heart that he learned to live with, like a mule with its burden. Many find distance from home liberating from context, but my father knew his limitations. He knew no limitations without land.

– Malavika Rajkotia, Unpartitioned Time

Jindo, his mother Bibiji and his wife Darshan continued to live their lives grappling with the loss of their selves and home, trying to rebuild a new one for their children Malavika and Ganeve. However, as is the nature of trauma, however unseen and unspoken, it transmits on to the young, who observe and sense much more than is imagined. Despite the blanket of comfort that the adults spun around the children with fruits, lassi and homemade butter, the heaviness of existence groaned in the form of the door that connected the kitchen and dining room.

Ghosts in the House: Partition’s Lingering Shadows

The groaning swing door was a constant sound of Rajkot House. It announced the movements between kitchen and dining room and also seemed to describe our life; it was happening but groaning with effort.

– Malavika Rajkotia, Unpartitioned Time

The memory of Partition lived like an unseen ghost in the house, appearing at certain moments, like the moment the Guru Granth Sahib arrived in the Rajkot house.

Recommended Reading: A Hidden Gem of Partition Literature

“What happened to the Granth Sahib in Rajkot Gujranwala?” asks a young Malavika, referring to their ancestral home in Pakistan.

“Their family was away at that time, as you know, so it must have been burned by the mob,” replies her mother.

A Dreamlike Childhood in Post-Partition Karnal

After the young girls were put to bed, the adults would continue talking into the night, often about the lives they left behind. Jindo’s depression was a dark truth that the family lived with, yet the book is sprinkled with Jindo’s witticisms, or ‘jindoisms,’ as Rajkotia calls them.

Recommended Reading: Why You Must Read Nanak Singh’s A Game of Fire After Hymns In Blood

Malavika Rajkotia’s narration is languorous, much like her father’s state in his old age. The anecdotes and stories linger like clouds on the reader’s mind. Rich with the wisdom of Sikhi, myths and fragments of history associated with Karnal, a nondescript town on the outskirts of Delhi, an almost dreamlike description of her relaxed childhood, the passage of time marked by the replacement of durries with carpets, the arrival of cinema theatres and television, the reader is left awash with peace much like after a dip in the sarovar (holy pond) of a bygone time.

Short Stories, Long Shadows: Post-Partition Meditations in Malavika Rajkotia’s Unpartitioned Time

In Malavika Rajkotia’s Unpartitioned Time, the narrator remains an unintentionally passive witness to the lives of those who carried on after the Partition, whose unspoken pain and inner struggles are sometimes revealed in a look or a word. For example, Jindo’s outburst at the realization that he was not educated enough to hold a job in the new country or Darshan’s discomfiture while attending weddings in Delhi, where people spoke in English, a language she struggled with.

The short chapters, simply written yet steeped in wisdom, retrospection, and rumination, though at times loosely connected, are a meditation on life after a tragedy, in which belief in humanity blooms like the flowering trees Jindo nurtured in his lifetime.

Have you read this book about the resilience of families rebuilding after immense loss, the silent transmission of trauma, and the beauty of finding humanity in the ruins of history? Share your thoughts with us in the comments below!