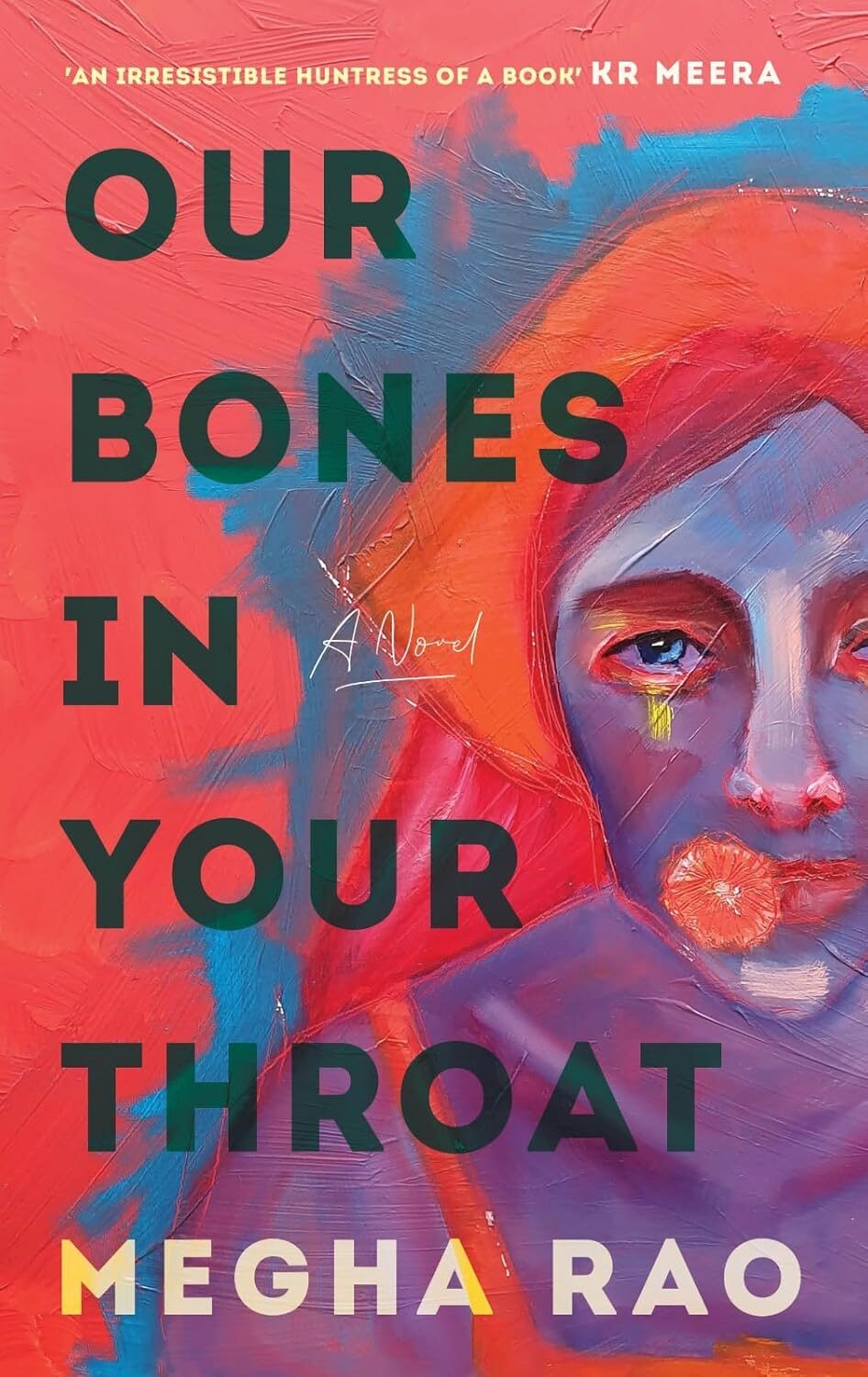

Prakruti Maniar reviews Our Bones in Your Throat by Megha Rao (published by Simon & Schuster India, 2024).

Our Bones in Your Throat is Megha Rao’s debut novel, a magical realism story about a girl’s quest for revenge and how faith, determination, words and poetry can have the power to bring justice.

The plot follows Esai and Scheherazade, two freshers at the legendary St. Margaret’s College, who strike up a deep friendship and go through the ups and downs of being students in the big city. Esai is a fierce young lady who wants to help others and give her friends strength when they are down. Scheherazade is a doubt-ridden poet in an abusive relationship who works with Esai to first find her footing, then help her peers find their voice against injustice, and finally, overthrow the college itself.

Recommended Reading: Rucha Chitrodia’s It’s Also About Mynah

It’s an ambitious tale from the very beginning, set in a near-mythical college campus, complete with a forest and a forbidden lake haunted by the ghost of the student’s past, whose own story we follow as the plot jumps between the past and the present. Few campus novels in Indian English writing attempt something of this imaginative scale.

But good intent does not make a good novel. Everything from the plot’s progress to the climax to the writing style and the treatment of characters works against the book, not just from a reading experience but also from the rules of good prose writing.

Setting and Scene of the Crime

The first thing that immediately hits you is St. Margaret’s, the main setting of most of the novel, a Hogwarts-esque campus, complete with a forest and a forbidden lake, and the ghost of Minaxi, a former student, that apparently haunts it. It takes a while to suspend your belief and accept St. Margaret’s, to not equate Minaxi with Moaning Myrtle, or often even Esai with Hermione Granger. Even the plot device used to tell us Minaxi’s story, in her words, is derivative of the pensieve from Harry Potter’s own quests with witnessing the memories of someone other than himself.

Recommended Reading: Find support in Shreya Ramachandran’s book about mental health

The other major setting is the city of Bombay or Mumbai, which Rao tries to infuse with the dreamy romanticism that we have come to associate with it, speaking of beaches, vada pav, Marine Drive, Kala Ghoda, and every token Mumbai element that you can think of. But it fails. Most descriptions of the city are rushed and read like they come from borrowed wisdom, not lived experiences.

Good city descriptions come from the details, local shops, gullies, beaches and other spatial elements used to really bring a city alive. Here, we only get the generic platter that’s devoid of nuance.

Characters and the Roles They Play

The city does not work as a character, nor do most of the characters themselves. The book is written in first person from Esai’s point of view, and unless it was intentional, each character is two-dimensional. Most characters even stay the same throughout. Minor characters are used in service of the theme to drive home a point about either racism or the power politics of sexual abuse, disappearing right after their purpose is served, only to reappear conveniently at some key moments. They appear only as examples, not people with complete lives and personalities.

Most secondary characters are treated as either black or white, few grey areas of human psychology and motivation are explored. See how Joshua, one of the book’s lesser-liked characters, is introduced:

“He was a brat. A man-child. He was one of those I knew I could never be friends with because of what they stood for. Fascism, hate speech, blaspheming minority religions. Joshua sought controversy and he got away with it because he was socially advantaged.”

Esai has proclaimed all this even before she interacts with him. Most characters are set up that way; traits are used to define the character, not the character exploring to find their traits.

At other times, details about a character are randomly introduced and then forgotten. For example, somewhere on page 209 (over halfway into the book), we find that the stress of college politics has taken a toll on Esai’s blood pressure, but nothing before or after reflects this health disposition. These token mentions could have been avoided or used more fully to develop the story to its full potential.

Recommended Reading: The Teenage Diary of Jahanara by Subhadra Sen Gupta

Writing: Tell Your Reader What To See, Not What To Think

Perhaps all of this might have been ignored if it had not been for the heavily used tell, never show style of writing that Megha Rao adopts. We never get to see things as they are, only the description of the thing. For instance, the library on campus is “time-worn, serene, and absolutely glorious“, but not one mention of the books it housed, the system of checkout it followed, how the shelves were lined if they were wooden or metallic, who else visited it.

Snippets of folklore and global history are peppered throughout, more like trivia than narrative hooks and additions, sometimes adding or doing nothing to a scene.

There is an excessive use of similes even where they don’t fit quite properly. Take this paragraph, for instance (Page 134), “As I hauled myself down onto the ground like a feather, I felt the cool dew…Everything around me pulsated as if it had a breath of its own. My surroundings appeared in high definition, like an eagle that had long-distance vision.“

Recommended Reading: 8 Indian young adult books you should checkout

Megha Rao is a spoken word artist whose work reflects themes of feminist angst, systemic injustice, and more. As such, Our Bones In Your Throat serves as a wrapper to an extension of Rao’s experience. But it has very little actual poetry and spends a lot of real estate trying to convince us that the poetry of the characters is good, so we must believe it.

Favourite Quote from Our Bones in Your Throat by Megha Rao

There are no witches. Simply casualties of hearsay.

Conclusion

Although it’s far from a perfect novel, Our Bones in Your Throat by Megha Rao is a fascinating attempt at campus stories, blending the genres of magic realism, feminism, and bildungsroman, among others. The friendship between Esai and Scheher is truly special and will remind you of the fights we fight for those whom we dearly love.

A firmer editorial hand would have benefitted it greatly. For its style and intent and its honest attempt at reaffirming our faith in the power of words and stories, I would recommend young women under 24 to definitely give it a read.

Have you read this novel depicting an epic journey through love, poetry, and rebellion at St. Margaret’s College? We want to hear your thoughts! Comment below and let us know.