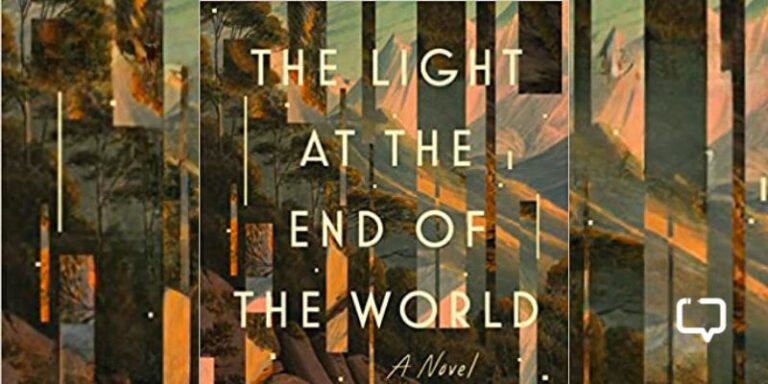

The author of runaway global success Kaikeyi (a reimagination of much-maligned warrior queen from Ramayan) has chosen to tread on placid waters this time with The Goddess of River, moving her quill towards the tome set in the turbulent times of the Dwapar epoch, the one sandwiched between the idealistic Treta (when Ramayan takes place) and the times of pure darkness, the Kaliyug (when the last Vishnu avatar is purported to descend on the doomsday.)

The Mahabharata, a sprawling epic written in more than two million words has been a fertile fodder for authors, especially in the last decade. Short stories gleaned from this epic have become commonplace in Indian literature across all languages. Reimagining the war and its effects through the eyes of primary or secondary male or female characters too has become common place, with authors building entire careers following this pattern.

In her second book, Vaishnavi Patel rewrites the Mahabharata from the point of view of Ganga, the goddess of the river.

This Story Begins With…

The story in The Goddess of River starts with Ganga descending upon the earth, but before she can hit this world with full force, she is bound in the tresses of Lord Shiva, who is to control the enormity of her flow and avert the loss of life. Shiva says: ‘If I were to release you now, your rage would still destroy much life here.’ She is furious with this entrapment and admonishes Shiva: ‘Gods cannot be captured!’

As she reaches Bharat (that’s how the land is addressed in the book,) she slowly grows to accept reality that she may never flow amongst the stars again.

One fateful day, the godling called Vasu, in order to punish the humans for taking more than what’s their due, steal a cow called Nandini. A sage then curses Ganga to come to the earth as a mortal and experience the human pain. Not only that, she would be the mother to the Vasus who had stolen the cow. The lines depicting Ganga’s mortification upon wearing a woman’s skin for the first time are admirably written.

Read on: ‘My fingertips were turning blue, like the edge of the sea, and I could no longer feel even pinpricks. I ran my pruned fingertips along the brown skin. These human senses were so limiting, horrifying. I had at least understood sight and hearing for my own perceptions mimicked them. But this, my fingertips taking on the feeling of another thing… Was this how humans experienced the world?’

The scene where she meets Shantanu for the first time is inventive and the writer tries to infuse much needed element of humour into the story. But because this humour comes from the observations or reactions of the minor characters, it didn’t hold much truck with me. It somehow felt as if author wanted the reader to laugh at Ganga, not with her. It feels a little awkward.

The Goddess of River, yes, but perhaps not of writing

The story is set in a different time and although I understand that a king must speak in sort of holier-than-thou phrases, the dialogues were often stilted.

Here’s a sample: “You, lady of the mountains, are unlike anybody I have ever met, and I have met a great many women. Come with me to Hastinapur. You shall want for nothing.”

If that’s how kings speak, I petition their words to be somewhat reworded.

However, the scenes and lines that depict Ganga’s psyche as she leaves her water existence and is forced into a human skin and life are well-written.

When I was a river, people touched and used me as they pleased, but I had never minded; water was for sharing–skin was not. In this new shape I needed to be far more careful.

Patel has started The Goddess of River with a content warning. She writes that Mahabharata consists of every terrible act one can imagine. Her book too touches upon these: infanticide, casteism, and ableism. The last, because Dhratrashtra was passed over for the throne because of his blindness. The scenes that depict Ganga letting go of her children and drowning them in the river are harrowing. The writing is intense and sharper than a copper wire pulled across heart. Patel shines in scenes of loss and longing, her writing feels more at-home in these passages. It slackens a bit when the story moves towards other major players.

The highlight of The Goddess of River remains Ganga’s musings, even when they interrupt the flow of the narrative, bringing novelty to an age-old story. Read it for her.

Best quote about being a mother

But a mother could not protect her children from all pain, no matter how she might try. It was folly, and those follies had led the whole world here, to these plains of suffering.