Somehow I feel that an ordinary person – the man in the street if you like – is a more challenging subject for exploration than people in the heroic mould. It is the half shades, the hardly audible notes that I want to capture and explore.

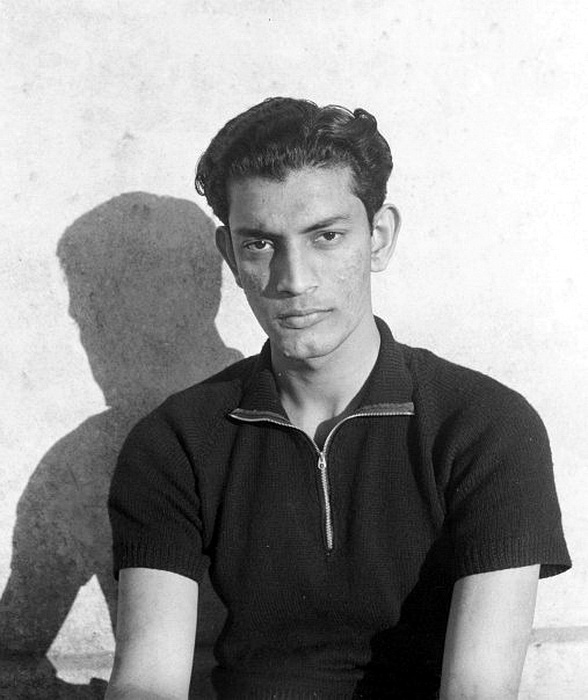

Satyajit Ray

I recently read how there’s nothing such as “being ahead of time.” That there are certain truths, and it’s the ability to accept those truths that vary with time. It’s an intriguing idea, and from that perspective, Satyajit Ray spoke truths through his cinema and stories. He redefined Indian cinema like no one before or after has been able to, with movies that are as enchanting today as they were decades ago. Today, let’s explore Satyajit Ray and his brand of cinema.

A Visionary Filmmaker

Born in Calcutta in 1921, he was born into a family of artists and intellectuals, with diverse influences from a young age. Upendrakishore Ray Chowdhury, his grandfather, a writer and painter, brought colour painting to Bengal and was one of the earliest pioneers of art and literature. Satyajit would spend hours and hours at his studio as a child, particularly interested in the children’s magazine, Sandesh. Sukumar Ray, his father, was a famous writer, illustrator, and poet, known particularly for his children’s stories. Satyajit inherited a love for storytelling from him, too, and would later translate many of his stories into English.

Moreover, he was exposed to world cinema from a young age, with maestros like Charlie Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, and Buster Keaton leaving their impacts. His other inspirations through the years included greats like Jean Renoir, Vittorio De Sica and Jean-Luc Godard. But it was his years at Santiniketan, the university set up by the Bengali philosopher and thinker Rabindranath Tagore, that sowed the metaphorical seeds of his filmmaking journey.

It’s rather easy to imagine a young Satyajit Ray learning the basics of visual storytelling amidst Santiniketan’s charming (romantic, even) surroundings. Tagore’s ideas would shape Ray fundamentally and his philosophy of universalism, of combining modernity with traditions, is apparent in the latter’s storytelling later. Outside the philosophical inspirations, Satyajit Ray would often use Rabindra Sangeet (the music of Tagore) to convey the spirit of his movies.

The Artistic Evolution of Satyajit Ray

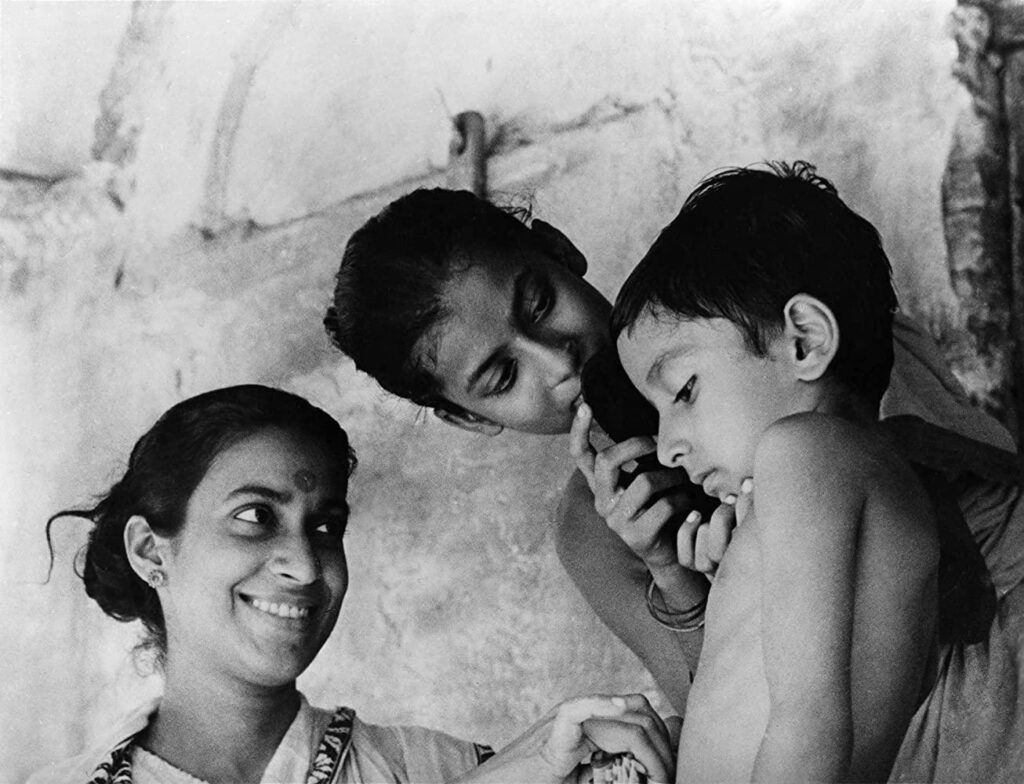

It was in the mid-1950s that Indian cinema would observe one of its watershed moments with the release of Pather Panchali. The story behind the making and the word-of-mouth popularity is almost as iconic as the trilogy he’d go on to make. Based on the eponymous novel by Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay, the movie was inspired by the neo-realist European movement while portraying rural Bengal like never before. Pather Panchali would lead the way to Aparajito and Apur Sansar, a trilogy that follows its protagonist, Apu, from childhood to adulthood. Love, loss, self-discovery, and the human condition in all its simplicity and clarity are some overarching themes of these movies (and Ray’s filmography, at large, one can say).

With the success of the Apu Trilogy, Ray got the liberty and the confidence to carve whichever path he wished for himself. He’ll dip his toes in new thematic and stylistic avenues throughout his subsequent films, whether character studies or historical dramas. Regardless of the genre, however, his movies explored the depths of the human condition. Take Charulata (an adaptation of Tagore’s Nastanirh, tr. The Broken Nest), the story of a lonely housewife who finds intellectual and romantic stimulation in her husband’s cousin, creating conflicts both interpersonal and intrapersonal conflicts; or Jalsaghar (an adaptation of an eponymous short story by Tarasankar Bandyopadhyay), where an aristocrat refuses to let go of his lavish lifestyle despite his world crumbling.

Recommended Reads: Satyajit Ray – Selected Fiction & Non-fiction

Then there are the interpersonal dynamics and romantic entanglements of the four urban folks on a countryside trip in Aranyer Din Ratri (based on a novel of the same name by Sunil Gangopadhyay), fleshing out the existing social norms and class distinctions; and a matinee idol revealing his vulnerable inner self, troubled by existential demons, completely in contrast to his cocky, larger-than-life image to a journalist whilst on a train ride in Nayak.

Outside the complex character studies, his directive vision shone through every work, even when the finances were, well, non-existent, like in Pather Panchali. His aesthetic sensibilities were remarkably distinct from the cinema of his times: an elaborate production design with dim lighting and complex furnishings in Jalsaghar, the long takes, non-professional actors, and natural settings to depict rural Bengal in Pather Panchali, a swinging camera to depict a heart in motion and using silence as adeptly as music in Charulata.

The Cultural Impact of Satyajit Ray

Satyajit Ray’s cinematic impact can best be seen through the new form of cinema rooted in realism and humanism, in stark contrast to the formulaic melodramas of mainstream Bollywood, and the portrayal of marginalised voices on screen.

He travelled in unconventional directions, treading outside the existing hierarchies: showing the plight of an untouchable man at the hands of the village priest in Sadgati (based on a short story by Munshi Premchand), the misery of a young girl trapped in a religiously fanatical and orthodox patriarchal family and society at large in Devi (based on a short story by Prabhat Kumar Mukhopadhyay), the journey of a woman toward freedom amidst societal expectations and pressures in Mahanagar (an adaptation of the short story Abataranika by Narendranath Mitra).

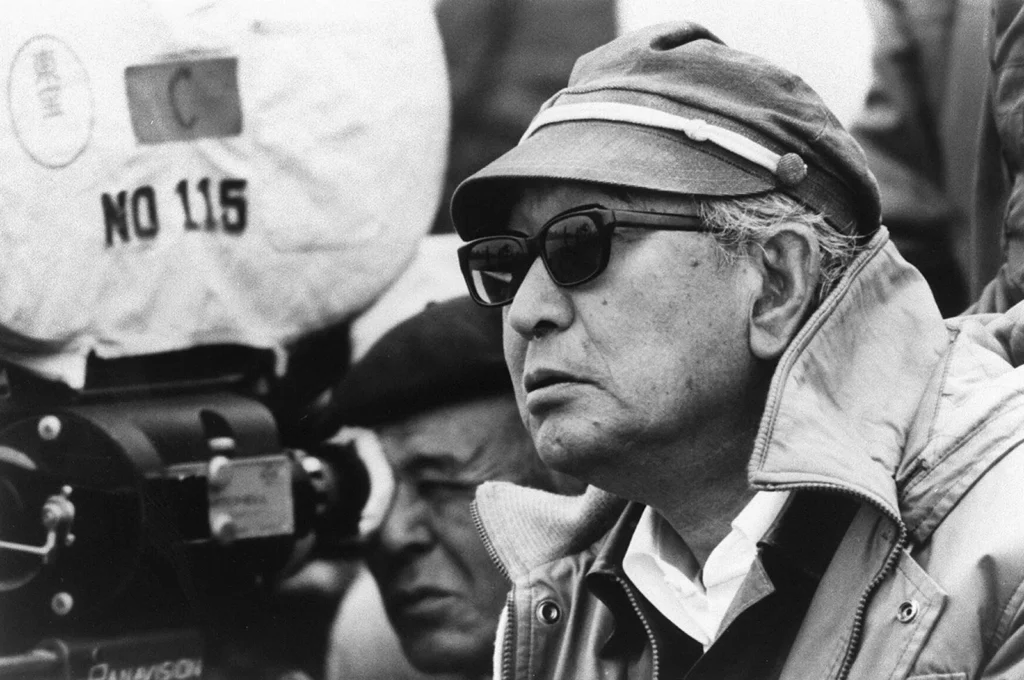

While you’ll easily find scores of listicles on “Hollywood Directors Inspired by Satyajit Ray,” a colonial hangover that refuses to let go, of seeking legitimacy and approval from the West, at the same time, it’s no secret that Ray was truly a global filmmaker. Whether it was in his inspirations or those who were inspired by him, national borders were largely inconsequential to his cinematic vision and legacy. He’s inspired legends like Shyam Benegal, Srijit Mukherjee, Martin Scorcese, Wes Anderson, and George Lucas. Akira Kurosawa, whom Ray admired back, has famously said:

Not to have seen the cinema of Ray means existing in the world without seeing the sun or the moon.

A Timeless Legacy

At a time when creative expressions seem to be stifled more with each passing day and when orthodoxy seems to indomitably rise in pitch and frequency, Satyajit Ray is more relevant than ever. His films inspire and provoke in equal measure while presenting the many shades of existence. They show the power of art to transform and critique society and its evils, to share the universal values of humanism, and to understand what it means to be human.