My current opinion of Shashi Tharoor, that of him being more of a dilettante than a dignitary, is, of course, solely a lament of his once-astute gifts of polemic and storytelling, which were found in spades in his single notable work of metaphysical fiction-cum-roman a clef, The Great Indian Novel.

The topical resonance of that work, published as the country was in the throes of an unpredictable 1990s, when Indians were finally coming to terms with the many travesties in its post-independence political narrative, made the novel, itself raw and rough-edged in places when it came to telling a story confidently enough, something of a modest classic.

We encourage you to buy books from a local bookstore. If that is not possible, please use the links on the page and support us. Thank you.

In between, he lampooned, quite cockily, Bollywood in Show Business and released his impressively congenial short fiction in the ensemble called The Five Dollar-Smile and Other Stories. But ever since he ventured deeper into the relative comfort of non-fiction, the calm neutrality of his writing and cool rationale of his observations have been gradually replaced by a cloying sense of repetitiveness, of saying the same things again and again, to the point of frustration, no matter how relevant those things might be.

This is not only observable in his more “serious” books which deal again and again with the same challenges and opportunities facing the country but also, to glaring effect, in Riot: A Novel. More of a cartwheeling commentary on India’s vain struggle against the demons of communalism in the throes of one of its darkest historical chapters and less of a straightforward narrative, the novel could have done very well to be merely the former instead of trying half-heartedly to evoke some suspense. It is not so much that the political heft, firmly in favour of secularism, is a problem; it is rather Tharoor’s art that fails him and us here.

Simply put…

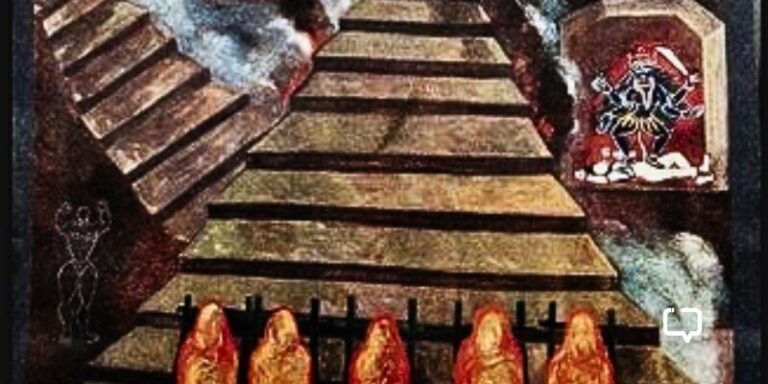

Riot is about the sudden and unexplained murder of Priscilla Hart, a 22-year-old American volunteer in the midst of a violent communal riot in a sleepy town in Uttar Pradesh. The year is 1989, that explosive epoch when the fundamentalists and fanatics were riding the surging wave of the communal tides of the Ramjamnabhumi movement. There is no conclusive evidence as to who has killed Priscilla, let alone the motive which is even more dubious; who would, after all, at a first glance, want to murder this girl, unknown to any of the fanatics on each side, who was working here on a covert project to help women with birth control and family planning? All that is left are her nearly blood-soaked diary and a few stray remnants of her bare existence in this town sweltering and simmering with bigotry and hatred. And they don’t reveal anything of particular significance.

Right from the beginning, it is evident that Tharoor is not interested in the procedural or even multiple whodunnit theories, both of which would have made it pulpier, but also admittedly more fun a read. Rather, by also scattering transcripts of long, rambling conversations, curiously one-sided monologues that run for pages and the occasionally truly interesting asides or scenes recorded in diaries or letters, he is more interested in cramming in more characters than can be developed fully or even credibly within the space of the book and try as valiantly as he could to lend each one of them a voice.

Too many cooks, too much broth…

So, just short of some pages, we have Priscilla’s parents (a once-philandering ex-pat father brooding on his guilt and a grieving mother), a district magistrate who is avoiding inconvenient questions politely, an American journalist who is quite desperate to get the whole scoop on paper and a few people who were either in the thick of the communal violence or faintly familiar with Priscilla, already contending for our attention. It is tricky but in the hands of a more deft storyteller, it makes for a compelling premise. Tharoor is not that deft storyteller.

The more pivotal characters that the author throws in are the most problematic. Take Laxman, the idealistic, soft-spoken yet unforgivably flawed district magistrate with whom Priscilla, as written in her letters to her friend, begins a tumultuous affair. He starts off as a likeable enough person but once in the throes of his affair with Priscilla, it soon turns into a sickening and self-centred obsession. It is hard to feel anything other than despicable repulsion at a man this selfish, who partakes more than his share of sensual pleasure in this tryst but cannot quite stand up for it honourably or even understand Priscilla’s understandable predicament. Yet, Riot, unnecessarily, devotes a chunk of the novel to his selfish intentions and beggars our sympathy when it could have been wiser and more heartfelt for it to lend a stronger voice to what Priscilla is going through. She is hardly believable; the writer sexualises her to such an extent that she ends up existing, for the most part, in Laxman’s perverted fantasies.

Add to that his foul-mouthed policeman Gurinder (are all Sikh policemen this high-strung and bitter, Mr Tharoor?), his erudite friend Professor Sarwar who lends many wise soliloquies but has actually no significant role to play in the novel’s events and even a despicably scheming fundamentalist politician, all of whom come across as mere caricatures only with occasionally eloquent words to spout, and we soon lose interest in a narrative that wanted, quite intriguingly, to investigate the scene of the crime itself rather than the actual murder.

Are good intentions enough?

And that brings me to the rest of the novel itself. If Tharoor is so concerned (and admirably so) with blaring out a national integration message, well, you know, we all want to change the world. But that message, no matter how well articulated in English that would make most of us budding writers chafe with envy, just does not deserve this blunt treatment. More skilled writers would have blended the political and personal more seamlessly but Riot is trying too hard to balance both on an even keel and fails to sustain interest. After setting up the stage quite confidently in the first hundred pages, the story runs out of vigour and energy.

There are many interesting distractions, nevertheless. Thanks to me reading it at an early age, I am still able to rattle off exactly what Coca-Cola had to put up with in India after the Emergency. There are moments when the Oscar Wilde-quoting Laxman becomes a more agreeable character, recounting his fervent boyhood dreams of a romance in the Western fashion as a complete contradiction to the humdrum reality of his arranged marriage. More than anything else, or even good storytelling, Riot at least succeeds in deconstructing the mythical allure of the uneasy romantic complicity between East and West, between the once-colonised country and the new domineering superpower. But, if only the rest of the book was as potent as this.

Favourite Quote: (This is something that we all should agree with):

An India that denies itself to some of us could end up being denied to all of us. This would be a second Partition: and a partition in the Indian soul would be as bad as a partition in the Indian soil. For my sons, the only possible idea of India is that of a nation greater than the sum of its parts. An India neither Hindu nor Muslim, but both. That is the only India that will allow them to continue to call themselves Indians.

Recommended For: If you want some thoughtful and well-articulated lessons of secularism, do read the book but if you are looking for a great book, with compelling characters and even a subversive premise, you can look elsewhere for that.

Suggested Reading: Khushwant Singh’s classic Train To Pakistan is also about the devastatingly personal effect of a national travesty of a much larger scale and impact. It is also a far better-written and narrated story.