Literary adaptations in Indian cinema are rare.

Great literary adaptations in Indian cinema are rarer.

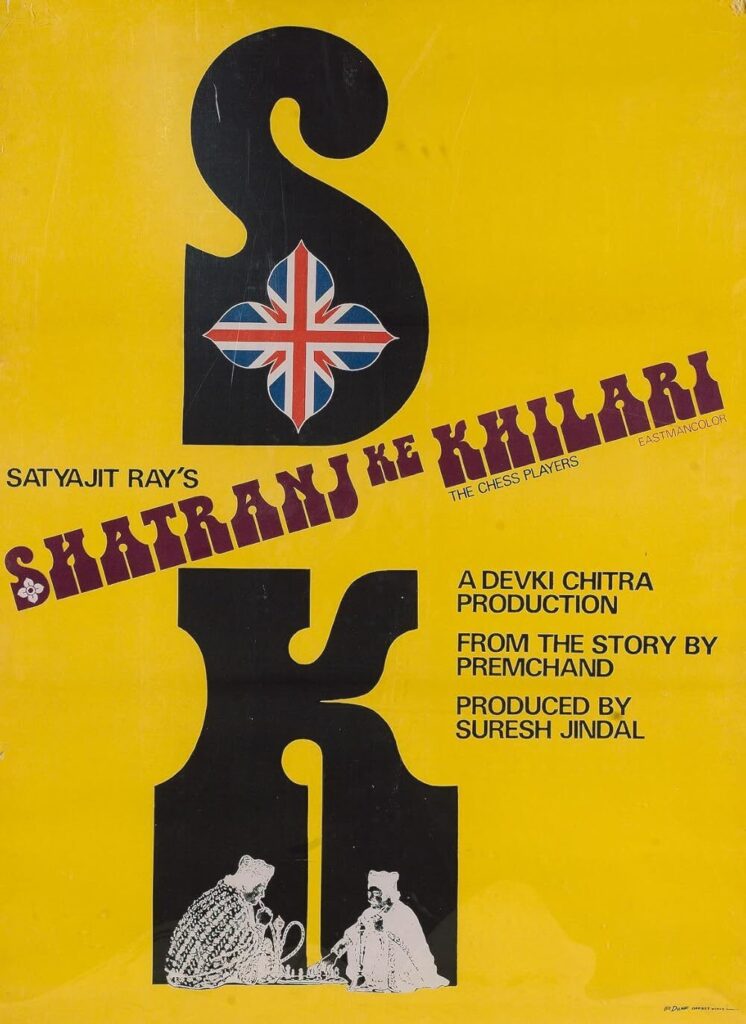

Satyajit Ray’s Shatranj Ke Khilari (1977), adapted from the eponymous short story by Premchand (1924), easily falls into the latter category. If you’ve ever tried searching for sports adaptations from Indian literature, you’d be sorely disappointed by the meagre numbers, that too all featuring cricket barring one.

Indeed, Shatranj Ke Khilari is the only non-cricket sports adaptation from Indian literature. But what were the similarities and differences between Satyajit Ray’s first and only theatrically released Hindi movie and the short story by one of the greatest Hindi-Urdu authors of all time? Moreover, how did Ray manage to create a story matching his vision while maintaining fidelity to Premchand’s tale? Let’s explore them in our essay.

Premchand’s Shatranj Ke Khilari

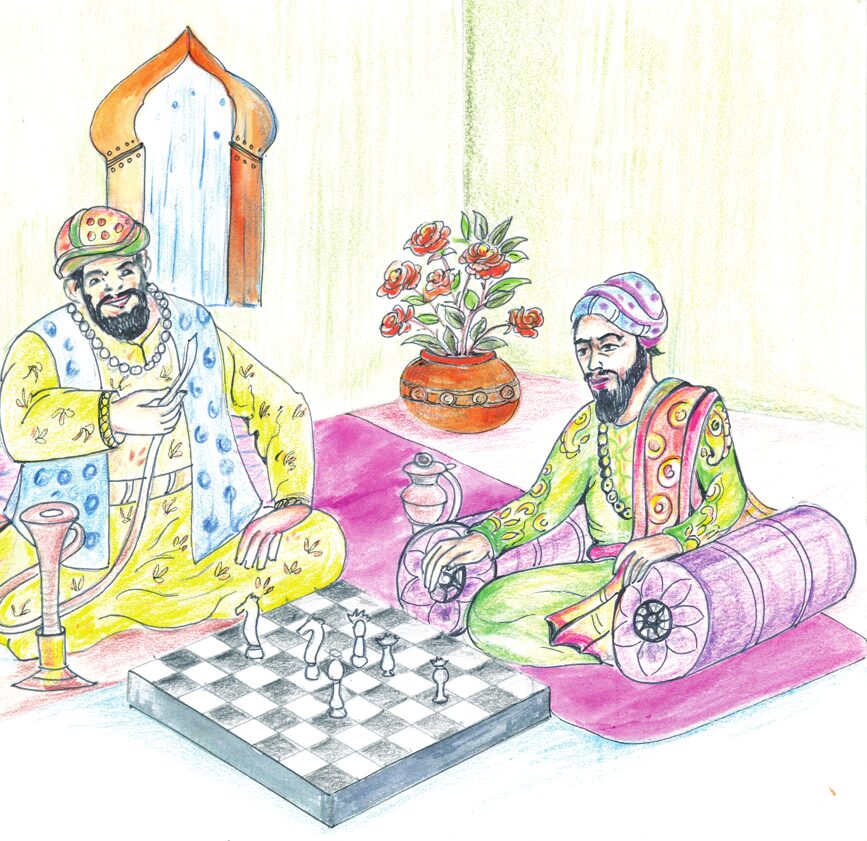

Premchand’s story takes the reader to the Awadh (Oudh) of 1856, a city deep into luxurious vanity. It’s a city cut off from the world, with administrative failures in every sector and an apathetic aristocracy detached from the issues of the population. The story focuses on two noblemen, Mirza Sajjad Ali and Mir Roshan Ali, both so entrenched in their games of chess (or shatranj) that they’re unaware of the happenings of the world around them, exaggeratingly symbolising the cities they resided in.

The story can also be seen as a cautionary tale against addiction. Though conventional readings of Shatranj Ke Khilari focus on the themes of escapism and depreciated culture, Premchand’s usage of chess and similar games in the same vein as opioids and liquor suggests there might be another angle to the story.

Premchand comments on the cowardice of the protagonists, their escapist tendency and irresponsibility, and the indifference of the ruling class to the sufferings of the common people. He uses chess as a metaphor for the larger socio-political dynamics of the time brilliantly, with many of his characteristic themes also featured in this short story.

वाजिदअली शाह का समय था। लखनऊ विलासिता के रंग में डूबा हुआ था। छोटे-बड़े, अमीर-गरीब, सभी विलासिता में डूबे हुए थे। कोई नृत्य और गान की मजलिस सजाता था , तो कोई अफीम की पीनक ही के मजे लेता था। जीवन के प्रत्येक विभाग में आमोद-प्रमोद को प्राधान्य था। शासन विभाग में, साहित्य क्षेत्र में, सामाजिक व्यवस्था में, कला कौशल में, उद्योग-धन्धों में, आहार-विहार में, सर्वत्र विलासिता व्याप्त हो रही था।

कर्मचारी विषय-वासना में, कविगण प्रेम और विरह के वर्णन में, कारीगर कलाबत्तू और चिकन बनाने में , व्यावसायी सुर में, इत्र मिस्सी और उबटन का रोजगार करने में लिप्त था। सभी की आँखो में विलासिता का मद छाया हुआ था। संसार में क्या हो रहा है, इसकी किसी को खबर न थी।

– मुंशी प्रेमचंद, शतरंज के खिलाड़ी

It was the reign of Wajid Ali Shah. Lucknow was steeped in a state of indulgence. Everybody—young and old, rich and poor—was immersed in luxury. If there were soirees of music and dance in some places, there were opium parties in others. In every sphere of life, enjoyment and revelry ruled. In politics and poetry, arts and crafts, trade and industry—everywhere—indulgence was becoming pervasive.

The courtiers were obsessed with drinking, poets with the descriptions of love and longing, craftsmen with making gold and silver embroidery, artisans with earning a livelihood from kohl, itr perfume, cosmetic paste and oils. In short, the entire realm seemed to be in the thrall of sensual pleasures. No one knew what was happening in the world.

– A Game of Chess, Premchand (quote from Stories on the City, edited by M Asaduddin)

Satyajit Ray’s Shatranj Ke Khilari

While the core of the story remains the same in the movie (outside of the relatively less tragic fate of our protagonists), Satyajit Ray adds a heavy sprinkling of social and political contexts. Using several historical records and memoirs, he portrays the Awadh of 1856 with his characteristic long takes and controlled background scores to create a powerful emotional impact. But unlike the inherent satire and jibes of Premchand’s story, Ray’s treatment is a lot more humanistic, something again very common in his movies.

Recommended Reading: A Revolutionary Vision in Motion: Satyajit Ray’s Iconic Cinematic Legacy

His characters, including the protagonists, are more nuanced and fleshed out, which, in turn, adds layers of irony and tragedy to the story. Unlike the Wajid Ali Shah in Premchand’s Shatranj Ke Khilari, Ray’s presentation of the nawab is kinder, sympathetic, and understanding of the many peculiarities of his times and life. He’s a patron of art and culture, being a poet himself, and his regimen is more aesthetically indulgent than administratively robust (largely because of the military control lying with the British rule).

His love for his land and people is shown through a passionate and imploring monologue after his Prime Minister conveys to him the new treaty the British rule wants to impose on the province, stripping the king of his power and roles.

Is it not strange, Prime Minister… that my ‘poor, oppressed people’… should make the best soldiers in the Company’s army? Half of Oudh has already gone to you, Company. Now you want the other half and the throne too. You are breaking one more treaty in asking for it. If my people are badly ruled, why have they not fled to a realm you own? Why do they not cross the frontier and ask you to save them from my misrule?

How Ray Builds on Premchand’s Shatranj Ke Khilari to Create a Masterpiece in Its Own Right

Unlike Premchand’s original Shatranj Ke Khilari, Satyajit’s characters aren’t mere symbols; they carry a historic legacy and value. Regarding our protagonists, Mirza (Sanjeev Kumar) and Mir (Saeed Jaffrey), they are shown in a more humorous light, a representation of merely one aspect of Awadh and its population. Ray translates Premchand’s scorn and sarcasm toward his characters into humour and tragedy. The primary character in Ray’s story remains colonialism, representing the never-ending greed of the English rule, foreign invasion, and the decline of a world and culture.

Recommended Reading: Shiraz Husain: Capturing the Death of a Monarchy

Ray’s direction beautifully captures the era of transition through the crumbling settings, the grand and simultaneously dilapidated palaces, and the changing temperaments. The music (composed by Ray himself) and cinematography (by Soumendu Roy) bring alive the Awadhi culture and its many colours and habits. As the Awadhi music gives way to the monotonous march sounds in the climactic scenes, you sense the upcoming change of British imperialism gobbling up the last “cherry.”

Our titular “chess players,” or the “shatranj ke khilari,” heighten the tragedy of the story instead of representing it in Ray’s adaptation. Through their common obsession with chess, as they remain spectators to these changing times despite having the means to play some part against the impending annexation, we can see the helplessness inherent to those times. The events almost become fated, each decision and reaction a careful sequence, and the transfer of power an obvious conclusion.

Conclusion

In a country where sports movies are few and far between and literary adaptations of sports adaptations even fewer, Shatranj Ke Khilari is a wind of fresh air. Like many of the greatest sports stories, both Ray and Premchand employ the game to make a larger commentary and depict the sociopolitical realities of our society. Thematically, there’s much to explore in Premchand’s short story and even more in Satyajit Ray’s rendition, and regardless of what you pick up, you’ll have a great time.

And who knows, maybe these “shatranj ke khilari” might lead you to other stories by these two legendary storytellers?