History is complex.

Quite complex.

And yet, all too often, our perception of our past is shaped more by the contemporary fashions of the day instead of some “objective truth.” Moreover, the world, for better or for worse, exists beyond the silos created by the internet and social media. For instance, there have been many landmark movements and protests through the decades of Indian independence that aren’t as popular today (either because they were largely ignored or have been eroded by the passage of time) yet remain a major and undeniable part of Indian history.

Today, we’re going to look at some of these movements, namely student movements in India that played a large part in shaping the nation. From the 1960s to the 2010s, from the Nav-Nirman Andolan to the Naxalbari movement, let’s take a detour through history and the many youth movements in India.

List of Student Movements in India

1. Nav Nirman Andolan (1974)

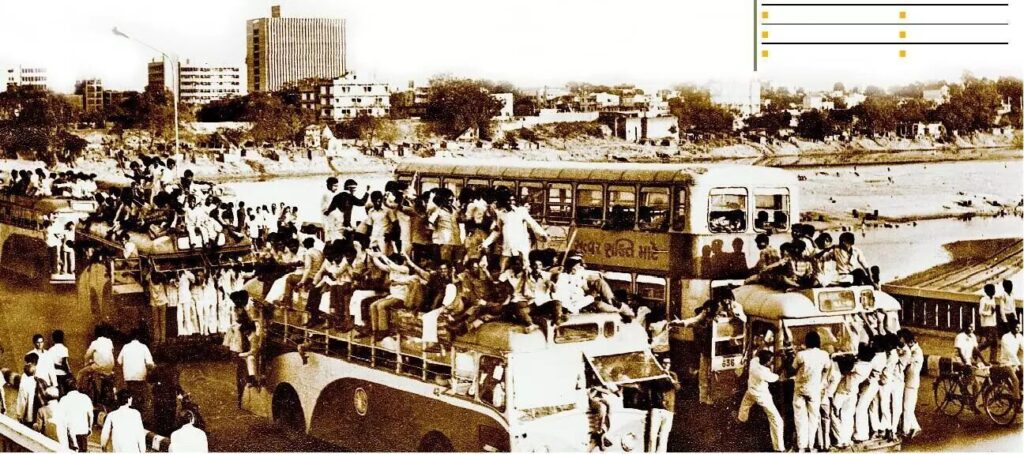

The Nav Nirman Andolan (trans. Reconstruction Movement) was a pivotal moment in post-independence activism and student rights in India. Starting as a protest in December 1973 against increased mess fees at L.D. Engineering College, Ahmedabad, it quickly grew into a larger movement against corruption, inflation, and poor governance under Chief Minister Chimanbhai Patel.

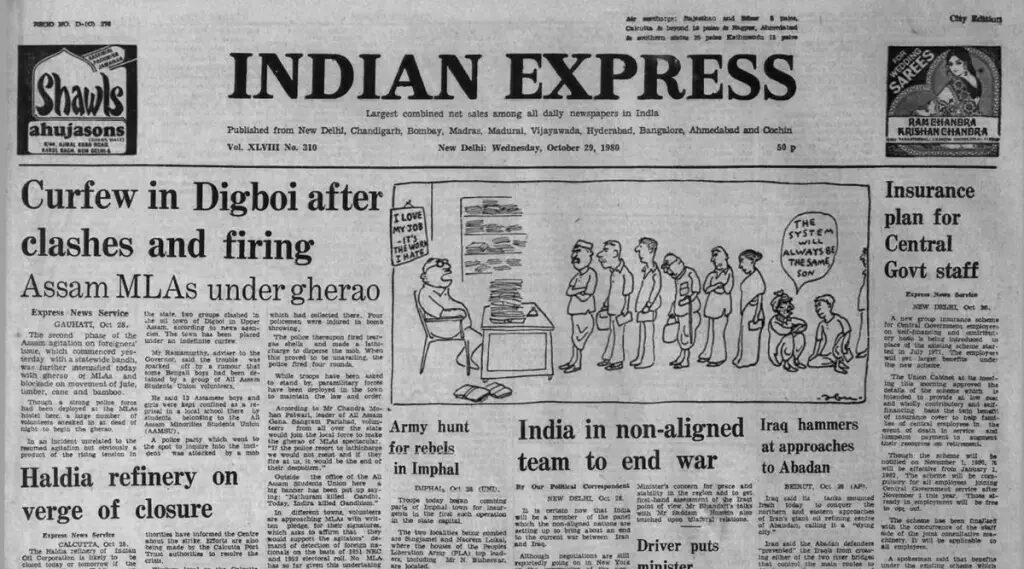

Role of Media and Organizational Influence

Media coverage largely helped amplify the protests beyond academic campuses. Newspapers and radio programs spread the protest across Gujarat, attracting the middle class, trade unions, and professionals. This is an important lesson, too. As we’ve seen all too often, media portrayal can play a big part in shaping a movement, whether positively or negatively, which is why a media group that’s outside of state control is necessary.

The Nav Nirman Yuvak Samiti, formed by students and citizens, became the movement’s organisational backbone.

Recommended Reading: Understanding Indian Social Movements: 20 Essential Movies to Watch

Involvement of Prominent Leaders

Morarji Desai, a senior political leader of the times, went on a hunger strike in March 1974, demanding the dissolution of the Gujarat Assembly. His fast fueled the momentum of the already powerful movement, forcing Chimanbhai Patel to resign on February 9, 1974, followed by the imposition of President’s Rule.

Jayaprakash Narayan, who visited Gujarat in February 1974, viewed the Nav Nirman Andolan as a precursor to the Sampoorna Kranti (Total Revolution) movement, a larger anti-authoritarian movement in Bihar.

Impact and Long-Term Significance

The Andolan was unprecedented in post-independence India. Student-led protests forced a state government to resign, demonstrating the strength of well-organised student movements in India to future generations. In the June 1975 elections, the Congress was eventually defeated by the Janata Morcha coalition, reshaping Gujarat’s political dynamics and influencing the rise of future coalition governments in India.

Relevance Today

The Nav Nirman Andolan remains a model for student activism even today, and its focus on fighting corruption and poor governance remains highly relevant. It’s an example of how grassroots youth movements in India can challenge and bring down entrenched political systems and has many valuable lessons in store for contemporary movements.

2. Anti-Mandal Commission Protests (1990)

The Mandal Commission, formed in 1979 during Prime Minister Morarji Desai’s tenure, aimed to assess the social and educational backwardness of the Other Backward Classes (OBCs). The commission recommended 27% reservations in government jobs and educational institutions for OBCs, adding to the existing 22.5% for Scheduled Castes (S.C.s) and Scheduled Tribes (S.T.s), bringing the total reservation just under the 50% ceiling mandated by the Supreme Court.

Why the Protests Began

In 1990, Prime Minister V.P. Singh’s announcement of implementing the Mandal Commission’s recommendations was met with widespread opposition, particularly among students. The protestors, primarily from upper-caste communities in Northern India, feared that the policy would undermine meritocracy and result in reverse discrimination in employment and education sectors. While political forces had a role, students were at the forefront of these demonstrations.

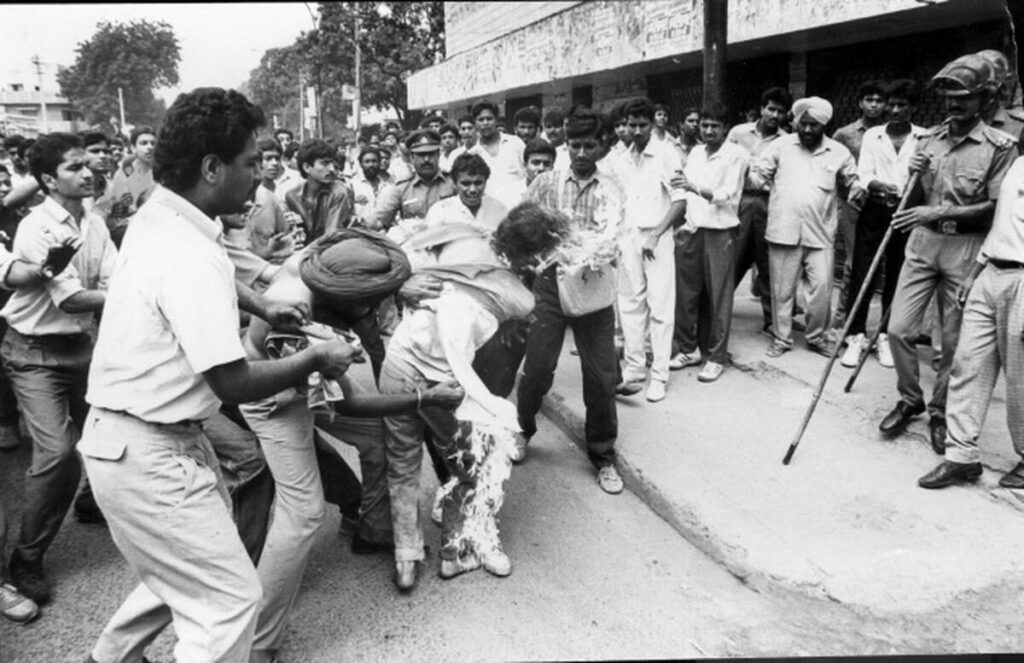

Key Features of the Protests

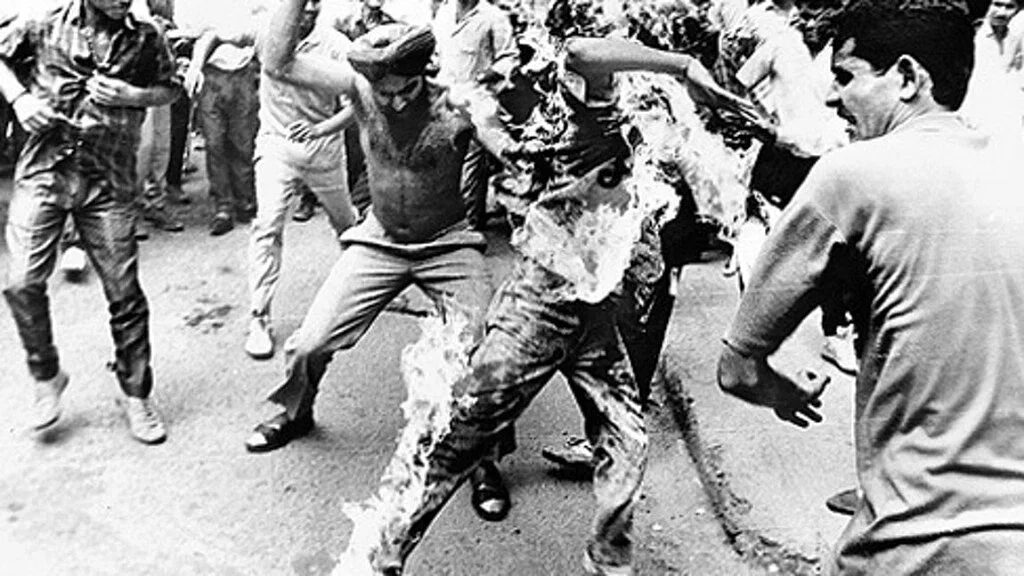

1. Student-led Movements: The protests were characterised by massive roadblocks, strikes, and demonstrations across Delhi, Bihar, and Uttar Pradesh. Self-immolations became a tragic hallmark of the protest, with Rajiv Goswami, a student from Delhi University, becoming a sort of national symbol after his self-immolation attempt.

2. Violence and Escalation: The protests escalated into violent confrontations with law enforcement. Public property was often targeted, and entire cities across Northern India witnessed shutdowns, affecting schools, businesses, and public services. The intensity of the protests paralysed many parts of the region for weeks.

3. Political Consequences: The anti-Mandal protests had far-reaching political repercussions. V.P. Singh’s government, unable to manage the backlash, eventually collapsed. The implementation of the Mandal recommendations deepened social divides, particularly between upper castes and OBCs, and reshaped Indian politics, fueling the rise of OBC-focused regional parties.

Recommended Reading: Greeting the Wolves: An Enquiry into O.V. Vijayan’s The Legends of Khasak

Role of Media and Organizational Influence

Again, the media was critical in amplifying the protests. National newspapers and television channels extensively covered the protests. Images of self-immolations, roadblocks, and clashes between protestors and police were widely broadcasted, galvanising public opinion both in favour of and against the reservation policy.

Regional Differences

While Northern India became the epicentre of these protests, Southern states like Tamil Nadu and Karnataka remained relatively unaffected. This was because these states had already integrated higher levels of reservations over time, and the concept of affirmative action was more broadly accepted in the South. The upper-caste population also formed a smaller percentage in the Southern regions compared to the North, making it less susceptible to large-scale protests.

Long-Term Impact

Although the protests failed to reverse the Mandal Commission’s recommendations, their impact remains profound. The demonstrations intensified debates on affirmative action, polarising the nation on meritocracy versus social justice. In 1992, the Supreme Court upheld the reservation policy but introduced the concept of the “creamy layer”, which excluded the wealthier and more privileged OBCs from benefiting from reservations.

Relevance Today

The issues raised during the Anti-Mandal protests remain highly relevant. Caste-based reservations remain a contentious issue, and debates around meritocracy, affirmative action, and social justice continue to shape Indian politics and society. The protests also paved the way for the rise of regional political parties that represented OBCs and other marginalised groups.

3. Assam Movement (1979–1985)

The Assam Movement, led predominantly by the All Assam Students’ Union (AASU), became one of the most impactful student movements in India. With the fear of unchecked illegal immigration from Bangladesh threatening their cultural identity and political leverage, the Assamese youth found themselves at the forefront of a movement that would reshape their state’s future.

Why the Protests Began

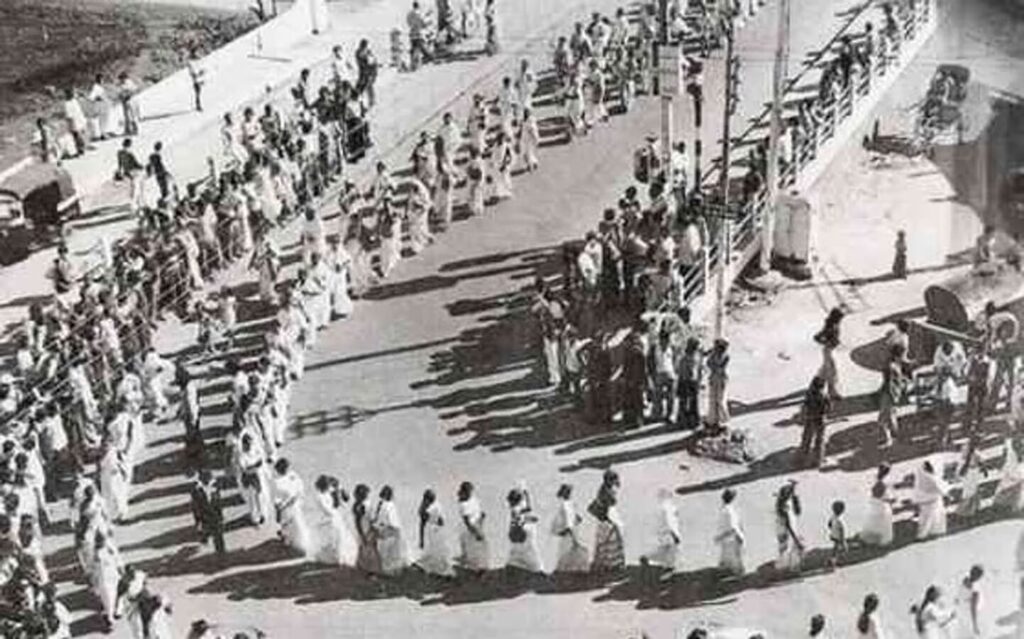

The agitation started in 1979 when a staggering number of immigrants were found on Assam’s electoral rolls. For many, this represented an existential crisis. The Assamese feared they would become minorities in their own homeland, losing both cultural and economic power to migrants. The student community, led by AASU, rose to demand the identification and deportation of illegal immigrants. They feared that unchecked immigration from Bangladesh would dilute their culture, seize their economic resources, and undermine Assamese political power.

Role of the All Assam Students’ Union (AASU)

The AASU carried this movement for over six years. Initially, their demand was straightforward: anyone entering Assam post-1951 should be expelled. However, as discussions with the Indian government progressed, the cut-off date shifted to March 24, 1971, coinciding with the partition of Bangladesh. The AASU got support from the All Assam Gana Sangram Parishad (AAGSP), and the fervour spread across Assam’s middle-class and rural populations like wildfire. What started as student-led quickly engulfed the entire state.

Escalation and Violence

While it started as a peaceful agitation, the Assam movement inevitably spiralled into chaos. Assam was shut down—literally—with strikes, protests, and hartals crippling daily life. The violence reached its peak during the Nellie Massacre in 1983, a shameful chapter of Indian history where over 2,000 Bengali-speaking Muslims were brutally killed. Assam’s deep-seated ethnic tensions boiled over, leaving the state divided between the indigenous Assamese and Bengali immigrants. Elections were boycotted, and violence ruled the streets.

The Assam Accord (1985)

The agitation concluded with the signing of the Assam Accord on August 15, 1985, between AASU, AAGSP, and the Indian government under Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. It set March 24, 1971, as the official cut-off date for identifying illegal immigrants—those who entered before were granted citizenship, and those who came after were to be deported. But this wasn’t just about immigration. The Accord also promised Clause 6, which assured constitutional and legislative safeguards to protect Assamese identity. However, as history would tell us, promises on paper often take years to materialise in reality.

Recommended Reading: Chipko Movement: How Grassroots Activism Changed Environmental Laws

International Concerns and Bangladesh’s Role

The Assam Movement had broader implications beyond India’s borders. It placed a significant strain on India’s diplomatic relationship with Bangladesh. The call for deportation wasn’t just a domestic issue, for it led to diplomatic tensions between the two neighbours. While India was firm in its stance, Bangladesh refused to fully acknowledge the large-scale migration. This reluctance created a complicated scenario where border management and migration became geopolitical puzzles that neither country could completely solve.

Post-Accord Struggles and Implementation Issues

The Assam Accord might have been signed, but implementation, especially of Clause 6, has remained incomplete. Assam still struggles with the very issues that spurred the movement. The National Register of Citizens (NRC) and the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) have reopened old wounds, with many in the state feeling that the CAA contradicts the Assam Accord by potentially allowing a large influx of migrants. The indigenous population’s fear of being sidelined has not entirely abated. Assam’s history remains deeply intertwined with its immigrant past, and the Accord, despite being a significant political milestone, hasn’t fully healed the divisions it was meant to address.

Role of Media in Amplifying the Movement

The media played an undeniable role in elevating the Assam Movement to a national scale. Both regional and national outlets extensively covered the protests, highlighting the deep cultural and political crisis Assam was going through. The sustained attention helped keep the movement’s demands in the public consciousness, creating pressure on the central government to act. This was a time when the power of media as a tool for social change became evident.

Environmental and Economic Concerns

Beyond the immediate political and social ramifications, the Assam Movement had a less-discussed environmental dimension. With large-scale immigration came intense pressure on Assam’s already fragile natural resources. Agricultural lands were overburdened, forests began to shrink, and resource depletion became a growing concern. These environmental worries only heightened the already fraught debate on immigration, as many saw unchecked migration as a direct threat to Assam’s ecosystem and sustainability.

Political Impact

The Assam Movement did more than simply reshape the state’s political landscape. It led to the rise of Prafulla Kumar Mahanta, an AASU leader who went on to form the Asom Gana Parishad (AGP). In a rare instance of a student-led movement successfully transitioning into political power, Mahanta became the Chief Minister of Assam after the 1985 elections. This was a seismic shift in Assam’s politics, cementing the importance of regional identity-based governance. The movement’s legacy continues to influence the state’s political narrative today.

Relevance Today

The Assam Movement remains highly relevant today. Issues of illegal immigration, identity, and citizenship continue to dominate Assam’s political discourse. The NRC and CAA have brought the movement’s core issues back into the spotlight. The failure to fully implement the Assam Accord, especially Clause 6, remains a sore point. Students, political leaders, and civil society groups still invoke the spirit of the Assam Movement when discussing the preservation of Assamese identity and the broader immigration policy in India.

4. J.P. Movement (1974-1975)

The J.P. Movement, also known as the Bihar Movement or Total Revolution, remains one of the most powerful student movements in India. Led by Jayaprakash Narayan (J.P.), a veteran freedom fighter and social reformer, this movement symbolised the fight against corruption, authoritarian governance and the breakdown of democratic values. The concerns raised then remain equally relevant today.

Economic and Political Backdrop

The socio-economic environment of India in the 1970s was a pressure cooker, bursting with public frustration. High inflation, soaring unemployment, and the post-1971 Bangladesh War crisis weighed heavily on the nation’s mood, and there was general disillusionment with the ruling government under Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. Food prices were skyrocketing, essential goods were in short supply, and widespread corruption in governance only deepened the discontent. Discontent had been brewing since the 1960s, and by the 1970s, it was clear that people, especially students, wanted change.

Why the J.P. Movement Began

The movement’s roots trace back to Bihar in 1974 when students at Patna University launched protests against the local government’s corruption and failure to address inflation and joblessness. As the protests expanded across the state, students sought leadership from J.P., who responded with the call for Sampoorna Kranti or Total Revolution. His vision was ambitious: not just minor reforms but a complete transformation of India’s political system to root out corruption, fix bureaucratic inefficiencies, and tackle social inequalities.

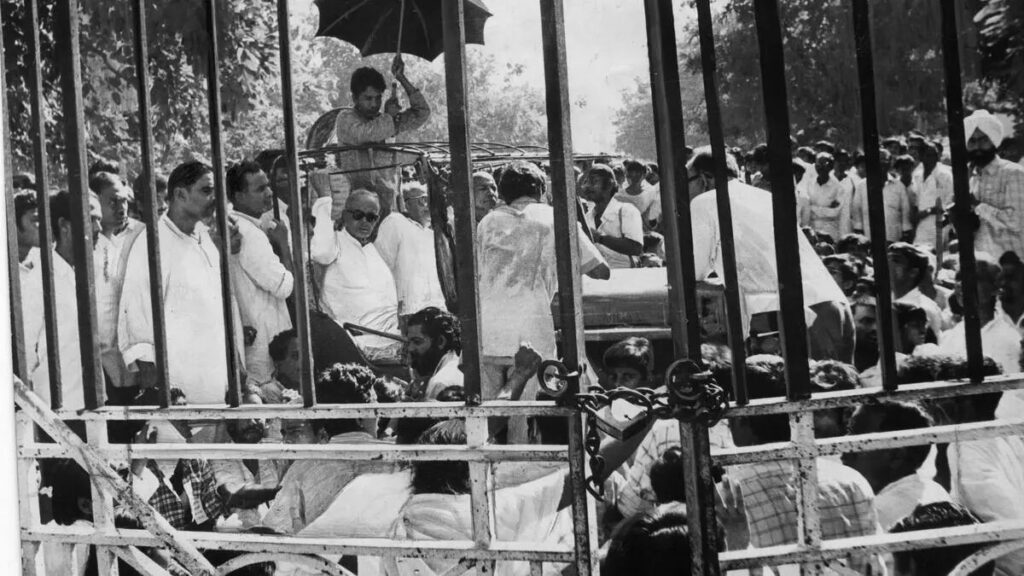

J.P.’s charisma and calls for peaceful, non-violent resistance attracted students from across India. Soon, opposition political leaders and activists rallied behind him. Protests spread across Bihar and northern India, with students organising massive rallies, strikes, and marches. These demonstrations, while initially peaceful, eventually faced violent clashes with the police, leading to numerous arrests.

Role of Students and Escalation

The Indian students were at the heart of the J.P. Movement. In cities like Patna and Delhi, students led large-scale demonstrations, decrying corruption, unemployment, and inflation. Jayaprakash Narayan emphasised the need for non-violent resistance, yet the escalating conflict with police forces led to multiple violent episodes. A major protest at the Bihar Assembly in March 1974 led to the deaths of 27 people in just one week.

Recommended Reading: Resistance Literature in India: Through the Years

The media helped increase the movement’s reach, with national coverage keeping the protest themes of corruption and authoritarianism alive. This media exposure created broader support for the movement across India, turning the protests into a national outcry for accountability and change.

The Political Consequences and Emergency

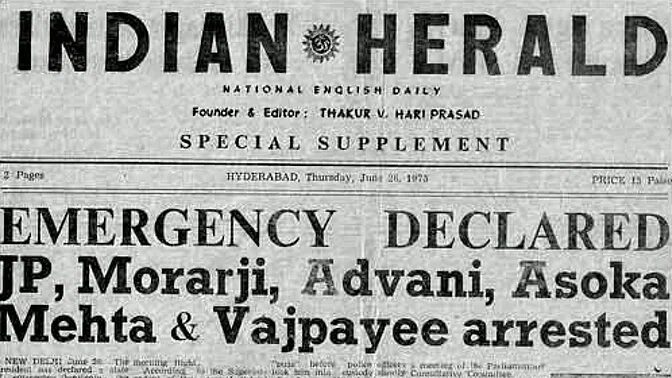

The turning point for the J.P. Movement came in June 1975 when the Allahabad High Court found Prime Minister Indira Gandhi guilty of electoral malpractices, effectively disqualifying her from holding office. Emboldened by the court’s decision, J.P. and his followers intensified their demands, calling for Gandhi’s resignation. In a dramatic response, Indira Gandhi declared a state of Emergency on June 25, 1975, suspending civil liberties, imposing press censorship, and arresting J.P. along with other opposition leaders.

The Emergency is now observed as one of the darkest chapters in Indian democracy. Thousands of political opponents, activists, and students were jailed. Civil liberties were virtually extinguished, yet the J.P. Movement—despite being temporarily stifled—left behind a foundation for future political realignments. Many student leaders, like Lalu Prasad Yadav and Nitish Kumar, who had cut their teeth during this movement, would go on to play major roles in Indian politics.

Long-Term Impact and Legacy

The J.P. Movement is remembered as one of the most significant mass movements in post-independence India. It exposed the growing dissatisfaction with the political establishment and laid the groundwork for the Janata Party, which eventually defeated Indira Gandhi in the 1977 elections, ending her Emergency rule and restoring democratic order. The movement’s demand for transparency, accountability, and democratic reforms remains relevant to this day.

Recommended Reading: 12 Recommended Post-Emergency Indian Literature: The 1980s

Beyond its immediate political consequences, the J.P. Movement also reshaped the landscape of Indian politics. Many of the student leaders who participated in the movement went on to play important roles in state and national politics, and the movement inspired future generations of political activists. The movement also reinforced the power of student movements in India to challenge government policies and reshape the nation’s political narrative.

Relevance Today

Even decades later, the J.P. Movement’s central themes—fighting corruption, resisting authoritarianism, and demanding governmental accountability—are just as pressing in modern India. The movement is frequently cited as a defining example of how grassroots activism can effect real political change, and its lessons continue to inspire newer movements for democratic reforms and social justice.

5. Anti-Hindi Agitation (1965)

When it comes to student movements in India that shocked the nation, one can’t miss the Anti-Hindi Agitation of 1965 in Tamil Nadu for the sheer impact it had on language politics in the country. The movement reshaped the socio-political landscape of Tamil Nadu and, by extension, the entire country. While students spearheaded the movement, the larger issue at hand was about identity, autonomy, and the fight against perceived cultural dominance.

Historical Roots

The agitation of 1965 wasn’t a spontaneous outburst but a culmination of a long-standing resistance to Hindi imposition dating back to the 1930s. In 1937, C. Rajagopalachari, the then Congress chief minister of Madras Presidency, attempted to introduce compulsory Hindi in schools. This move faced fierce opposition from the Self-Respect Movement led by Periyar and the Justice Party, with the protests marked by processions, fiery speeches, arrests, including prominent leaders like Periyar and C.N. Annadurai, and even deaths of protestors Natarajan and Thalamuthu. It was a precursor to what would unfold three decades later. The language wasn’t just a medium of communication but the very essence of identity.

The 1965 Protests

With the 15-year constitutional deadline for making Hindi the sole official language looming, tensions escalated in Tamil Nadu. The death of Jawaharlal Nehru in 1964 only made a sensitive situation worse. For Tamil Nadu, this felt like history repeating itself. Fearing that Hindi would replace English in government jobs and further alienate non-Hindi-speaking states, the students, especially in Madurai, kicked off protests that rapidly spread across the state. What began as rallies soon escalated into violent clashes. Around 70 people, many of them students, lost their lives during this period.

One of the most powerful moments of the agitation was when Chinnasamy, a young man from Tiruchirappalli, immolated himself in protest—a tragic symbol of how deeply people felt about the cause. His death, along with many others, pushed the movement into a larger national debate. The protests reached such a fever pitch that Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri had to step in and promise that English would continue to be used alongside Hindi for official purposes.

Relevance to Society Today

This movement was about much more than language. It was about rejecting domination—culturally, politically, and economically. Language politics in India, especially in Tamil Nadu, continues to be a hot-button issue. Tamil Nadu’s two-language policy (Tamil and English) remains firmly in place, and every time the subject of Hindi imposition arises, the legacy of the 1965 agitation resurfaces.

Impact on Contemporary and Future Society

Political Impact: The most immediate result was the meteoric rise of the DMK. The Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), which had campaigned strongly against Hindi imposition, swept the 1967 elections, marking the end of Congress rule in Tamil Nadu. The DMK’s victory went beyond the political, for it was a cultural statement. From then on, the Dravidian movement would dominate the state’s politics, focusing on Tamil identity and autonomy.

Cultural Impact: For Tamil Nadu, this movement cemented the idea that Tamil was the heart of their identity. The state took significant steps to promote the Tamil language and culture, and to this day, Tamil Nadu remains protective of its language, ensuring that policies reflect this commitment.

Recommended Reading: Language Politics in India: Regional Protests and Their National Implications

National Impact: The protests pushed the Indian government to pass the Official Languages Act of 1967, which guaranteed that English would continue to be used in official capacities alongside Hindi. Without this movement, India’s linguistic landscape might have looked very different. The agitation forced India to rethink its language policy, ensuring a more pluralistic approach.

Economic Dimension: This was also about access—particularly to jobs. For many in Tamil Nadu, the fear was that Hindi imposition would make central government jobs inaccessible to non-Hindi speakers. The resistance, therefore, while cultural, was also economic to ensure that Tamil speakers weren’t sidelined in the broader economy. Language was seen as a barrier to opportunities, and students were determined to keep those doors open.

The Lasting Echo of the Movement

The Anti-Hindi Agitation of 1965 reminds us that movements often go beyond the surface issue—in this case, language—and touch the deeper questions of identity, power, and equality. The impact of one of the largest student movements in India continues to echo through Tamil Nadu’s politics, culture, and even India’s federal structure. Today, Tamil Nadu’s resistance to Hindi remains firm, and every time language politics surfaces, this chapter of history is revisited. Yes, it was a movement about language, but it also ensured that a diverse country like India respects the unique identities of all its people.

6. Rohith Vemula Protests (2016)

The Rohith Vemula Protests were a watershed moment in modern Indian activism and student movements in India. They erupted after the tragic suicide of PhD student Rohith Vemula on January 17, 2016, in Hyderabad. His death highlighted the entrenched caste-based discrimination that continues to affect students, particularly Dalits, across Indian universities.

Why the Protests Began

But Rohith Vemula’s death didn’t happen in a vacuum. Rohith was among five Dalit students suspended by Hyderabad Central University after a clash with the right-wing student organisation Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP). Why so? The Ambedkar Students’ Association (ASA), of which Vemula was an active member, protested against the ABVP’s disruption of a documentary screening. ASA had organised a screening of the documentary Muzaffarnagar Baaqi Hai, and ABVP members opposed it. Accusations were thrown, but it was the ASA students—without any substantial evidence—who the administration targeted for this seemingly small event, cut off from their stipends, and barred from the hostel and common areas.

Recommended Reading: A Mahar speaks: Daya Pawar’s Baluta

Vemula’s suicide note was a painful indictment of the institution and society’s treatment of Dalits. “My birth is my fatal accident,” he wrote. His death was seen beyond its individual tragedy: as the culmination of institutional casteism—what many termed an “institutional murder.”

Student Involvement and the Role of Media

The protest wave that followed Vemula’s death was largely student-driven, with Ambedkarite student bodies, left-wing organisations, national organisations like the All India Students’ Association (AISA) and the Students’ Federation of India (SFI), and students from all across India coming together to demand justice. The outrage went beyond Hyderabad Central University, with universities from Delhi to Mumbai and Kolkata holding vigils, strikes, and marches.

Online media was crucial in magnifying the protests. Vemula’s final letter spread across social media like wildfire, galvanising public opinion. His words became symbolic of a larger fight against caste oppression in Indian universities and the societal structures that enable such discrimination. The protests quickly became about much more than Vemula—they reflected the systemic challenges faced by marginalised communities nationwide. This widespread media coverage further drew in political activists and human rights defenders.

Key Features of the Protests

Campus Movements: The heart of the protests resided in the university campuses. Students organised rallies, sit-ins, and hunger strikes, demanding justice for Rohith and the resignation of Hyderabad University’s Vice-Chancellor Appa Rao Podile, who was accused of playing a direct role in the suspension that pushed Vemula to despair. Legal action was also sought against Union Minister Bandaru Dattatreya, who had intervened against the Dalit students, accusing them of “anti-national” activities.

Broader Conversations: Beyond the immediate demands for justice, the protests reignited debates on the state of caste-based discrimination in academic institutions. There were calls for the implementation of a “Rohith Act,” which would institutionalise safeguards against caste discrimination in educational institutions. Although this act hasn’t materialised, the demand for such systemic changes remains.

Long-Term Impact

The Rohith Vemula protests had far-reaching effects, forcing many institutions to confront their own complicity in perpetuating casteist structures. While immediate structural reforms have been slow, the conversation around caste in academic spaces has been permanently altered. More students are now speaking out against caste-based harassment and demanding inclusive reforms, emboldened by the movement sparked by Vemula’s death.

Recommended Reading: Waiting for a Visa by BR Ambedkar

Relevance Today

The issues Rohith’s story brought to the surface—caste-based discrimination, exclusion, and marginalisation in academic spaces—are as urgent today as they were then. Conversations around caste and educational inequality have not gone away. Caste-based discrimination is still rampant in India’s academic institutions, and the movement continues to inspire student movements in India aimed at dismantling systemic oppression. The fight for more inclusive policies and equitable spaces for marginalised students is ongoing.

Rohith Vemula’s name remains synonymous with this fight, a call to action for those still striving to dismantle centuries-old hierarchies in education and beyond.

7. Naxalbari Movement (1967)

The Naxalbari Movement of 1967 was a full-blown call for revolution that sent shockwaves across the nation. Sparked in a small village in West Bengal, this peasant uprising didn’t stay local for long. It found resonance with students and intellectuals who saw in it the potential for the kind of sweeping, systemic change that India’s deeply entrenched socio-economic structures needed. While its origins may have been rural, its influence reached far and wide. This movement eventually paved the way for the Naxalite-Maoist insurgency that India grapples with even today.

Why the Movement Began

The roots of Naxalbari lie in long-standing land disputes in the region. Sharecroppers, tribals, and landless labourers were systematically exploited by zamindars (landlords) who refused to give them their due share of agricultural profits or hand over land rights. Tensions boiled over when a group of peasants attacked landlords and killed a police officer in a clash over land. What followed was an uprising that lit the fuse on a much larger movement, with peasants arming themselves and launching attacks against the landlords.

The movement was deeply influenced by a mix of Marxist-Leninist and Maoist ideologies. Its vision was to uproot the existing social and political structures and replace them with a peasant-led revolutionary government. The movement’s leaders, Charu Mazumdar and Kanu Sanyal, would openly call for the overthrow of the Indian state through a “protracted people’s war.” They envisioned a new kind of governance led by peasants and driven by armed revolution—a bold and radical vision.

Student and Intellectual Involvement

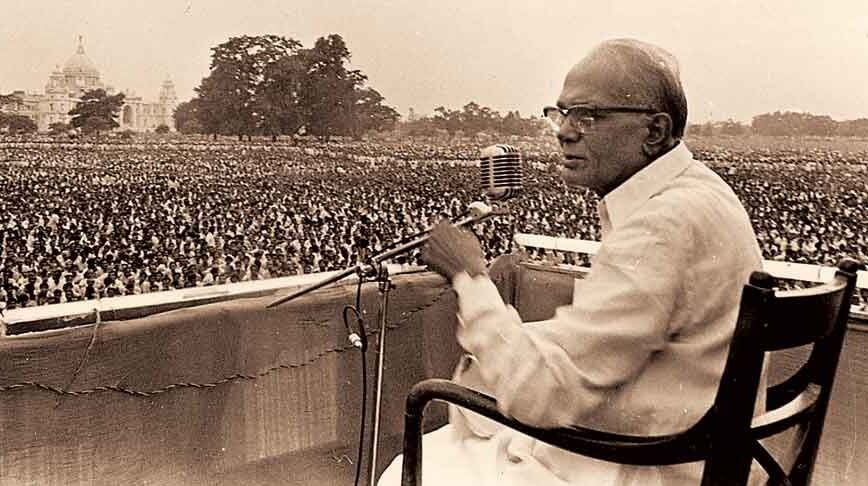

Though it was a peasant-led revolt, the Naxalbari Movement found a natural ally in the student communities, especially in urban centres like Kolkata. Students, many of them radicalised by Marxist ideology, were drawn to the cause. They saw it as a fight against the deeply entrenched inequalities of the Indian system—inequalities that were economic, social and political.

University students actively participated in protests, rallies, and even underground revolutionary activities, with slogans like “Amar bari, tomar bari, Naxalbari” heard across campuses.

Many students left their academic pursuits to join the revolution, seeing it as a chance to create a more equitable society. Several student organisations took up the cause, helping to mobilise resources and people, and played a direct role in the spread of Maoist ideology beyond West Bengal to capture the imagination of a generation disillusioned with the status quo.

The Government’s Response

Initially, the Indian government viewed the Naxalbari uprising as a local disturbance. However, as the movement gained traction in several states, the fact that it was more than just a rural skirmish became obvious. The state’s response was swift and severe. Operation Steeplechase, launched in 1971, was a coordinated military and police operation aimed at quelling the insurgency. Thousands of Naxalites were arrested, and many—including Charu Mazumdar—were killed or died in custody. The movement was brutally suppressed, but it didn’t disappear.

Instead, it went underground, evolving into the Naxalite-Maoist insurgency that continues to this day. The state’s response did not address the root causes of the rebellion—issues of land rights and social inequality remained unresolved, and these continue to fuel Maoist movements in India’s poorest regions.

Long-Term Impact

The Naxalbari Movement wasn’t some fleeting rebellion. It became the seed for the Naxalite-Maoist insurgency, which remains one of the biggest internal security challenges India faces today, still active today in the “Red Corridor,” a region that stretches across central and eastern India. The insurgency is a constant reminder of the unresolved issues that started the original revolt—land reforms, tribal rights, and rural poverty.

Recommended Reading: There’s Gunpowder in the Air by Manoranjan Byapari

Politically, the movement reshaped the landscape, particularly in West Bengal, where the Communist Party of India (Marxist) eventually came to power in 1977, granting amnesty to many former Naxalites. The movement also gave rise to a legacy of activism and student movements in India, with radical student groups continuing to push for systemic change long after Naxalbari.

Relevance Today

While the Naxalbari uprising occurred over half a century ago, the issues it raised are still incredibly relevant. India’s rural and tribal populations continue to struggle with land dispossession, poor governance, and social marginalisation. The movement forced India to confront the inequalities ingrained in its system—inequalities that, in many ways, persist today.

It also changed the trajectory of student movements in India, demonstrating the power students could wield in shaping national debates. The radical energy of the Naxalbari movement and the widespread student involvement can still be seen in various social justice movements across the country. It’s a reminder that revolutionary ideas, once ignited, can have far-reaching consequences, reshaping societies and politics in ways that are felt for generations.

Conclusion

Student movements in India have always been at the forefront of major socio-political changes, and the seven movements discussed here prove just that. Whether it was the Nav Nirman Andolan shaking up Gujarat’s political establishment or the Anti-Mandal Commission Protests shaping the conversation around caste-based reservations, students have sustained revolutions time and time again and forced the nation to confront uncomfortable truths.

From challenging corruption and authoritarianism in the J.P. Movement to asserting regional identity during the Anti-Hindi Agitation, students have historically led the charge against oppression and misgovernance. Even in movements where they weren’t at the helm, like the Naxalbari Movement, their influence amplified the cause, creating long-lasting impacts.

These student movements in India challenged the state, inspired future political leaders, and redefined notions of justice and equality in Indian society.

Students have always been at the edge of change, driving revolutions that force the nation to confront its deepest issues—whether corruption, inequality, language, or land rights. As these movements fade into the backdrop of history, the issues they raised—corruption, caste discrimination, regional identity, and land reforms—are still very much alive. The fight continues. And if history is anything to go by, students will continue to be the driving force behind the most transformative movements that lie ahead.