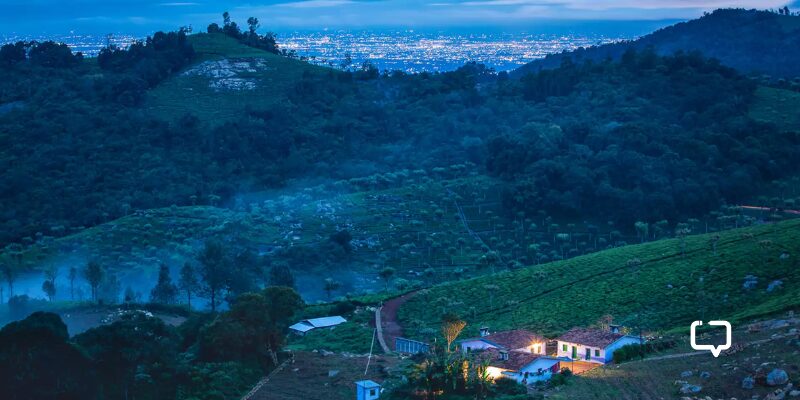

If I were to pick one word that is most sacred in my vocabulary, it would be Hethey (pronounced hae. tey). I am often told the hey sound, which is produced when soft air pressure hits the vocal cords, resulting in a short wave, was the first sound that escaped my mouth. Hethey means grandmother in Baduga, the language spoken only in the Nilgiri Mountains of South India.

Hethey is also the cardinal deity of the community, the ancestress who is revered across the hills. Hethey, to me, signifies the primordial sounds of the land that I share a deep relationship with, a phrase that was handed over to me through several generations in the past who venerated the word and world that it represents.

Badaga Language

Like most languages in the world, Badaga has its territory within the mountains of the Nilgiri district. For several centuries, the keepers of this language, the most populous community in the region, have cohabitated the terrain with other communities, each with their own language. Badaga (also written as Baduga), a proto-Dravidian language, is not a dialect of Kannada or any language as popularly believed.

With the unique retro-flex sounds and distinct phonology, phraseology and morphology that do not mirror any of the major languages spoken in the peninsula, Badaga (Badugu to a native speaker) is recognised as an independent language within the South Dravidian family, thanks to close to two decades of research by French linguist scholar Christiane Pilot-Raichoor. Most Badugas today are trilingual or bilingual. The literate can read and write in Tamil, the language of the state and English, the language of the colonists who inhabited the mountains for more than a century.

Baduga does not have a written form, and most communications within the community are carried out in Tamil. The rich oral literature is evident in ballads, legends, folklore, proverbs, ritual prayers, songs and even blessings offered. The lexicon lends a certain cadence to the literature, the beauty of which can be felt only when one listens intently. Deciphering the rhythms requires a certain level of intimacy with the language that millennials like me lack.

Every time I left the mountains, I kept this language behind at the foothills. My mother tongue was like a cloak I came home to at periodic intervals and removed and stored in safety when I left. However, in strange moments, its rhythmic flow has captivated even a sporadic speaker like me. At the annual festival for the Goddess Hethey, the songs sung in her praise, narrating her supreme power, reverberate across the valley.

The words, though sung in the present, have a deep history attached to them. In those moments, as the beauty of the words is enhanced by accompanying instruments, one imbibes the parts of the past spread out like an exhibit, trying to connect to every word in the song, like meeting estranged family members.

Language-People- Place

More often than not, it is the language that defines a culture or a community and gives a group an identity. Baduga is often described as spoken by the Badugas of Nilgiris. In this case, the language with thirty phonemes does not just define the people but the landscape, too. In many ways, the word, people and place are intertwined. Therefore, it becomes imperative to speak about the people, the keepers of the language and the biosphere they inhabit.

The Nilgiri Mountains are among the richest ecological regions in India. More than a thousand species of flora are endemic to this region. Since time unknown, a few indigenous communities have lived in harmony with the land. The Badugas, an agrarian and pastoral community, outnumber the other communities living here.

Badugas are a socially progressive indigenous community with an estimated 1,33,550 speakers (census dated 2011 by Government of India) living in 390 hamlets or settlements. Literature documented widely by anthropologists, including the likes of Paul Hockings, denotes the community as migrants from the northern part of Nilgiris. In his thesis titled Identity and Quality of Life Among Badagas in South India With Reference to Rural-to-Urban Migration and New Media, sociologist and professor Gareth Davey states otherwise.

He quotes, ‘My feeling of the literature is that the migration theory has been readily accepted and then weak evidence found to give it legitimacy. There has been too much reliance on folklore and the rough observations of Fenicio and early British census officials, coloured by political and religious ideology, and analyses of oral tradition of Badagas and other tribes seem rudimentary.’ Relying on Christiane Pilot-Raichoor’s study on the philology of the language and its grammatical homogeneity, Davey concludes that the community might have been created in the Nilgiris in ancient times.

He also points to the high incidence of sickle cell anaemia among the populace and the distribution of HLA antigen, which is common in other indigenous communities in the Nilgiris, to support his view. Irrespective of anthropological views, which I do not debate here, a close analysis of the rituals and practices points to extended mutual co-existence with the environment. These practices also affirm that such detailed knowledge of the terrain must have been gained over several centuries of close spiritual bonding with the landscape. It is not something that migrants with a few centuries-old history with the biosphere could acquire (or even aspire to acquire).

A Baduga person considered land as their identity and connection to a greater power in the universe and therefore, preserving the environment had been upheld as sacrosanct. In the funeral litany of the community, the elders gather around the corpse to ask for forgiveness for the sins of the departed. Among the sins listed are pollution of the stream, killing of reptiles and shattering a spurt of green. A moral way of life encompassed the environment and extended to all living beings in the highlands.

Uri hogi siri ba, Seerpare hogi singara ba, Huchu hogi sachu ba is the phrase Granddad blessed me with until the last of his days. This was something I heard often as a child, and until three years ago, I did not know what it meant. Thanks to the rhyme and meter, this phrase was never erased from my memory.

Bo endhu bokki, Kho endhu korasi is yet another blessing that is widely used by the elders in the community. Gho endhu gaai – Grandma often described the dry gale, gaai here meaning the wind. In my early adulthood, I was fascinated by the word origins in English, the language of my thoughts, and it struck me as odd that most words had their origins in other, older European languages. I have often pondered on the origin of words in my mother tongue, the iterations used as adjectives and the rhythms that fall in place.

Maybe they have their origins in the sounds of nature- the furious winds rampaging the settlements in the deep valley or the sounds of amiable breeze at the mountain peaks, the babble of pristine water in the brook running over pebbles and rocks as old as the mountains. They are perceptually sounds from the past, sounds of the land and all the wonders it holds.

The most commonly used procession chant ehh hau hau ehh hou hou is an acclamation that has echoed the most across the valleys and peaks around the Baduga domain. It is a chant used as any procession- religious/ritual moves ahead, and the sounds emanate deep within the diaphragm in the human body; it is an intense spiritual call. I have often equated it to the deep old pulse of the mountains.

Language and Traditional Ecological Knowledge

As per the Baduga-Tamil-English Dictionary by the Nelikolu Trust in the Nilgiris, most places in the Nilgiri hillscape had Baduga names until the 20th century. This changed with the ingress of people from other parts of the country. With the loss of Baduga place names, the geographic and ecological knowledge associated with the place also disappeared. However, the names of the hamlets and villages haven’t changed since they came into existence, and the same applies to the environment surrounding each of them. However, some of these names have been distorted through time.

My grandparent’s hamlet is in a deep valley. Around the village, every hill had a name and so did every slope and pasture and patches of land left unused. Sometimes, a different toponymy was used for spaces within a 100-metre distance. It was only recently I discovered that each of these spaces served a purpose in the past. What the villagers called the tho was the common cattle pen of the yesteryears and ore a few metres away was the grazing site.

Kambe, where grandma had her patch of land roughly around 800 metres away from her home, was called such because two mountain ridges met at that point, conjoined by a long, narrow route. The geedu that is close to the tho is the narrow mountain pass. The etymology behind Shortu, the tallest peak around the hamlet, which is considered sacred, is ‘moisture emitting rock.’ I often asked Grandma about this strange practice of naming spaces in close proximity.

She always responded that is what she was taught and never asked for reasoning and at times, she explained what these places meant. I vividly remember the late afternoon walks with Grandma to the plantations or farmland and back when conversations around nooks and corners in the locality and the stories they held flowed between us. She learned them from her mother-in-law and other elderly women in the village.

Every one of the roughly 400 Baduga hamlets and certain villages and towns spread across the mountains is named after different geographic features and vegetation, and the environs around the settlements were analysed and studied in-depth. It is interesting to note that these Baduga names that define the features and shapes of the mountains are as diverse as found in English, and in some cases, they do not have an English equivalent.

It isn’t just a valley in Baduga; the fringes of a valley, the basin of the hills, the base of a mountain slope, the foot of a hill, a deep valley and a narrow one, each have distinct words to describe them. The same applies to slopes. There are close to seven words, or perhaps more, that define a slope based on their altitude, inclination, presence or absence of rocks. When the mountain pass is narrow, it is called moge, and when broad, it is called aru. These are only a handful of examples. The Baduga vocabulary and traditional knowledge concerning the landscape and its silhouette are as broad and inexhaustive as the mountains themselves.

The name of every hamlet is rooted in its unique geographic feature or the vegetation it holds. The nooks around the settlements describe the shape of the plateau, the ridges hint at the presence of a stream or marshland/swamp/wetlands, or the saddle formation in the hills defines the curves or the patterns at the foothill and, in certain places, warns the possibility of flash floods or disasters the region is prone to.

This knowledge was handed to the present generations by a group of pastoralists who wandered across the expanse of the mountains, observed its intricacies, analysed every slope, meandered through the valleys and passes and explored the ridges, rocks and ranges, one step at a time. Every minute detail was held in memory, every tree and fern studied, and the course of waterways scrutinized before deciding on places suitable for habitation and marking hills and valleys worth preserving.

Conclusions must have been made after several generations of trial and error, guided by the soil their hands held and the rocky or tender surfaces of the highland their bare feet felt while walking. Walking aided a certain fathomless connection between the human body and mind with the landscape.

From those afternoon walks with grandma, I distinctly remember the babble of the spring in summer as we passed by, the crushing sounds of eucalyptus cones as we stepped over them, and the patterns of early monsoon breeze as we descended a hill and ascended a plateau. I remember the hill I called an inverted ice cream ball and the rock I called Dog’s Back.

It dawns on me now the kind of knowledge that can be acquired by deep and consistent observation of a landscape is profound and infinite. Author and aboriginal scholar Tyson Yunkaporta calls this deep-time thinking, which surfaces when there is an intimate relationship between a place and its community. The language thus born out of this kinship is sacred.

Baduga Language and its Present Form

During my adolescent years in the early 21st century, I often noticed that my grandparents used different vocabulary for common words. Household utensils, parts of the body and clothing had names that I had never heard of. I also understood that their vocabulary would diminish with them. However, conversations with their grandchildren were generously sprinkled with words from English. Colonial rule had left them with a sound knowledge of the language and even a fascination with it for some.

If words from other cultures seeped in during the 20th century, a native speaker’s loss of vocabulary happened in the 21st. Many reasons can be attributed to this. Without a written form, there was no documentation of the words used in the past. Literacy rates drastically improved post-independence, and a literate Baduga could read Tamil or English or, in most cases, both. Most people tend to internalise the language they read and write in and with every passing generation, the affinity and bond with the language of their ancestors gradually decreased.

With the people from the past generations, well-versed in proverbs and sayings gradually decreasing, a millennial’s exposure to them is limited. The old way of life is no longer relevant, and with the literary past gradually diminishing, songs and ballads, rich in form, content, alliterations and assonance that once echoed across the hills, are no longer intrinsic to the culture.

The fall in tea prices was the final straw. With the arrival of cash crops in the mountains, originally introduced by the British, many Baduga families forewent traditional crops like millets and shifted to plantations during the 20th century. Most of these small tea farmers depended on the price of tea leaves for living. While the cash crops did help the community gain economically, the drastic drop in prices of tea leaves in the early years of the twenty-first century changed the equations in the mountains forever.

With a rising difficulty in making ends meet and no time for experimentation or trial, most Badugas found an easy way out of the crisis- to sell land. With tea estates being sold, most natives moved away from Nilgiris and those who grew up here in those difficult years knew their life in the mountains had no future. The first two decades of the twenty-first century were marked by an exodus. A person moving to a big city had fewer opportunities to converse in their mother tongue other than with members of their community occasionally.

Thus, the literary form of the language was forgotten and the colloquial form is used only by the people residing in the hills. For people like me, who have lived away from the mountains for a considerable part of our lives, our mother tongue was what defined our home for much of our lives. We take refuge in the sounds and in the hills they belong to every time we visit our homes.

In the midst of change, there are a handful of old women in every hamlet, the last of the generations holding onto the old ways of life and words from the past. In my parents’ place of residence, three octogenarians still refer to places around the settlements with the old names.

The people who purchased the lands around Baduga hamlets gave their own names to the patches they owned. So, thore was replaced by Stream View, aada was replaced by Avenue, and, in some cases, the original names were distorted. Kodanadu, a popular tourist destination which means land’s end, as it is the border of the mountains, is now called Kodaenad, the nedil letter, a long vowel in Tamil, replaced by the shorter kudil.

If these sounds disappear from the mountains, it wouldn’t stop with the loss of the language of a community, but the entire knowledge systems and modes of livelihood that prioritised the land that preceded our time in history.

The Rising Need to Safeguard the Language

Baduga has been marked as a “definitely endangered language” by UNESCO. In a surprise announcement, the state government of Tamil Nadu, in its 2024 budget, allocated INR two crores towards the preservation of two endangered languages, which included Badugu. It remains to be seen what could come out of this initiative.

A handful of Baduga people, including language experts, bureaucrats, and scholars, have taken the initiative to keep the language and culture alive through various means. Among them, the efforts of Nelikolu Charitable Trust, a non-profit organisation, are worth mentioning. Active since 2003 and created with the purpose of documenting oral literature, the trust has followed UNESCO-recommended methods to preserve the language.

The Trust has been at the forefront of documenting the extensive Baduga orature. In an effort to introduce sounds of the language to young children, it has published study material on the language to primary grade children apart from various books for adults detailing language and culture. Among its greatest achievements is the compilation of trilingual Baduga-Tamil-English dictionary, a juggernaut initiative undertaken by several members of the community over a decade. The book also carries information about places inhabited by the community, its etymology, medicinal herbs used in the past and other relevant cultural details which came in handy while working on this essay.

Apart from the Nelikolu Trust, several passionate individuals contribute to this growing necessity of language preservation. Among them is Senthil Ramakrishnan, author of Aboriginal Badugas of Nilgiris (self-published), who is the person behind a website documenting nuggets of the history of the community (badugaa.com). He is an activist working on the ground, raising his voice against blind measures undertaken by the state impacting the land and its inhabitants. Also noteworthy are the works done by Dharmalingam Venugopal, Director of Nilgiri Documentation Centre, an archive of the mountains and Shivaji Raman, whose immense vocabulary helped shape the trilingual dictionary.

The one name that is synonymous with linguistic and cultural conversation in the mountains and beyond is Reverend Phillip K Muley, scholar and author. His contribution to the language cannot be summarised in a few sentences. He is the point of contact for every novice and learner finding his way into the cloud that is the history of the region. His warm home is a space that rewards every seeker with profound conversations beyond prejudices, and the gates are always open. Always.

Several web pages and social media handles have also contributed to keeping the conversations around language and cultural preservation alive. Accessible from every part of the world, these virtual conversations have been unifying members of the community for several decades now. Notable among them is badaga.co which has been active for more than a decade and a half, the site I often visited as a young adult with existential questions and from where I learnt interesting aspects of my history.

Is mere documentation enough to reproduce the magic of the language and all the information it holds? In Emergence Magazine’s podcast series, Language Keepers, a Karuk (native American) language speaker disagrees. He affirms that the dictionary is not the same source as its speaker. Having been raised in a close-knit community, I understand his statement.

I know the unique words my grandparents used and the tune produced by those words as they flowed out of their mouths. I know the pauses and drifts, the alliterations and reverberations. The process of learning and the way one has been taught play a crucial role in studying a language. When you imbibe the language in its spoken form, you know how to hold it within you and pass it on when the time comes.

It is being said that 40% of the world’s 7000 languages are in danger of survival. Among the greatest threats to these endangered languages are technology and the way systems have been programmed to cater to majoritarian languages in the world. However, there is room to harness this power in safeguarding the dying sounds across nations.

Language is therapeutic; it mends its speakers and listeners. In cities across India, especially in the metropolises in South India, speakers of the Badugu language have kept the spirit of community alive through associations that meet annually. Members of these groups brainstorm to overcome the problems pressing the populace both in cities and back home in the mountains. Songs, speeches and dances are intrinsic to these meetings and, for many a child who is the only Badugu speaker in his school or street, it is invigorating to meet others who share his linguistic heritage and to understand they are not alone.

In the case of Badugu, it is the language that gives a sense of stability to live in the mountains. I am unsure if that equation could be reproduced elsewhere. A language can be carried to places but I am sceptic about revitalising the environment it has thrived in.

Tyson Yunkaporta stresses that cultures should remain fluid enough and adapt according to the times to improve their longevity. Both the Badugu language and its speaker have changed with the times and now there are passionate individuals across the hills trying to preserve the invaluable fragments from the past. The time gone and the sounds from the past cannot be completely recreated, but work can be done in the present to the best of our abilities with the hope that someday it will make an impact.

My intermittent relationship with the language I inherited is for a lifetime and I will remain a responsible learner until the end of my days. I hope my descendants realise they come from a beautiful language, one worth safeguarding.

24 Responses

Great work Monu, just felt it’s bit melancholic to know that people don’t speak baduga when they are in the city, hope your essay provokes our community to hold on to our beautiful language by making it a practice to speak at home.

Thank you Akka. Thanks for reading.

It is indeed gives us the pride of baduga community and an elongated history well narrated.

Goosebumps moment.

Our respects to you Monisha Raman.🙏

Thank you for your kind words.

An excellent contribution to our younger generation.

My best wishes and proud to be badaga

Thank you very much.

Great initiative and well documented too Monisha ! Budhak ! Budhak ! I do agree with in alm aspects including the language part . It’s inevitable in all languages where words keep fading and undergo changes too. For instance words like : dhowe means smot / nasal mucus , Bandi – handful Kuppacha- shirt , Bapanay- morning like which the present generation are not aware of . As you rightly mentioned only documentation could help to preserve these data .

Landscape of hutty names too had been corrupted because of the local domination of Tamil . Dhavaney- Thavay anae, keya kundhe- Kil kundha, oranalli- ornnae, Munuhutty- Manihutty etc .The UNESCO categorised Baduga as a definitely endangered, I where most of our children speak other languages, it’s our duty to keep the language alive by ensuring our children speak the mother tongue out side Nilgiris. Let’s join together to bring this awareness and significance of of our mother tongue Badaga language. Long live Badaga culture & language !

Thank you for your comment. The words that you have mentioned are the ones my grandparents often used.

Great effort Ms.Monisha Raman.

Hats off to your love for our community and language.I wish,all badugas realise the truth behind our community.

Sometimes,i feel bad and disturbed hearing from Badugas parents insisting their siblings to speak in English while at home and where do children get to speak badaga in such a situation.With people migrating to cities in search of jobs and seeking education in the cities,they are mostly found speaking English , Tamil or the state language they thave moved to.

By birth, children should be told about our ancestral importance even though facilities and revenue in our native place is not sufficient to move on.

Anyway,let all of us take it seriously to do the Needful now before it’s too late.

Thank you for your kind words.

Good One Monisha !

Yes indeed, this is a language worth dying for. This is not just a language which is beautiful, but divine. It exhibits humility, respect, hospitality and more than anything else… therapeutic. You only realize this the more you speak.

Thank you, Vinay. Every language has its charm, but I wouldn’t die for it.

A fantastic article Monisha. It was an enlightening read. It’s high time we as a community join hands to preserve our beautiful language and the landscapes.

Thank you Venugopal.

An absolutely beautiful essay Monisha. Loved reading it so much.

Thank you so very much, Divya.

Very very proud to tell, “na ondhu badugathy.”

Wherever I meet a person in plains I speak to them in badugu only. It’s really a pride.

Hats off to you Monisha.

Let’s meet soon.

The world is round.

Thank you.

I believe everyone will read this essay and get some awareness to preserve our mother tongue.

Thank you.

I think , it’s really worthful if you were born before 80. Collapse of our language, tradition and cultures started from 80. On reaching 2020 many youngsters like you in our community starts researching in many dimensions, now we have books, dictionaries and letters. Really proud kids of 21st century not only hardworking also great admirers towards one language survivability. Hats off to you and your research.

Thank you very much.

Thank you for your kind words.

Hi Monisha …. any online class for badaga language

So that we can do better for next generation

JAYAPRAKASH halan