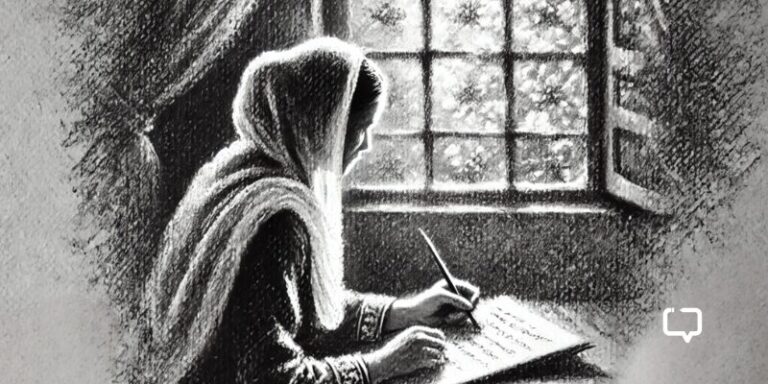

Shortlisted for prestigious JCB Award for his 2021 novel ‘The Plague Upon Us’, Shabir Ahmad Mir now brings a story of Kashmir replete with the land’s folktales: ‘The Last Knot’. Based in a Kashmir of 19th century but also a Kashmir of stories and legends, The Last Knot brings a gore-flecked reality of a tragedy wrapped in a shiny packaging of fantasy.

The intent is the same, akin to that of art: to give comfort to the uncomfortable and discomfort to those cocooned in soft cushions of privilege. Kashmir and its inhabitants are struggling and The Last Knot doesn’t let you forget that.

The Fort and the Carpet Weaver

Ahmad Mir skilfully words his story of Kashmir, without using any words that may be deemed ‘risky’ in the current political climate. To a reader with an eye for imagery, everything can be compared to the tense of now and present.

So, there is a fort atop a hill (Haer Parbat: there is a beautiful tale that the author recounts in the book) that sees everything and controls everything, including the weavers that weave carpets. Even a knot here and there and they shall know.

Know and object and imprison and torture.

The fort stands for everything tyrannical and imperial. It stands for chains, the restraints, and a hand clapped tightly shut over the mouth of the oppressed. But the ones with unrest in their mind shall always find a way to look for the just.

To look for the freedom and a chance to escape.

Ahmad Mir writes:

‘The master sings, the apprentices obey and this duet on the loom continues in mellifluous monotony and agonising repetition for months, if not years; each day adding just a barely perceptible but excruciating layer of colour and shape on the loom, as if one were measuring out the void of eternity in handfuls…’

The master stands in as a soft assistant to the fort. Where the fort cannot be, the master is. When the protagonist ends up making a carpet that lies limp like a corpse, he is filled with apathy and revulsion for following the pattern and singing to the tune.

He wishes to break the tune and weave a carpet that would fly. Abli Bab, a has-been carpet weaver who lives in a cave right under the nose of the controlling fort, tells him about a blue carpet enriched with a fabled blue dye and marked by Solomon’s star. This carpet, now lost to time, could be a key to our protagonist’s freedom.

The Dyer and the Daughter

The protagonist runs away and under the cloak of madness, starts living near the house of a dyer. His daughter Heemal, on a detour to fetch water for her controlling father (control makes appearance again, this time in guise of family,) ends up losing her earthen pot. The protagonist, to cement his madness, spits in her face. The dyer, to compensate for the loss of pots, takes him as apprentice. He soon shifts into the house and learns the secrets of dyeing.

Heemal, the dyer’s feisty daughter, has locked horns with her father. She, in no unsubtle words, shares with the weaver that her father could be inadequate at the business of dyeing and understanding the dyes.

She says: ‘A dye, any dye, is an impurity forced upon the fibre. Our ancestors knew that, as any dyer worth his salt would. The yarn must be pure before we make it impure. That is as good a lesson as any. Lesson, mind you, not some vulgar joke. You see, only that yarn which is pure will put on a colour you want it to, Otherwise, the impurity within resists the impurity forced upon it and the result is only as good as anybody’s guess.’

The words that spell the story of Kashmir

This story of Kashmir is teeming with words and phrases indigenous to region. The author patiently explains us the meaning of each word, without making his book look like a dictionary. Not even once did I feel I was reading a word I didn’t know about.

The prose is honeyed and yet it brings a discomfort that’s the demand of the story and its nature – like this phrase: ‘animosity is the dowry of secrets.’

Best Kashmir Quote

‘Do I really have a choice in all this? Did I choose to suffer like this? Can I choose anything else but an end to this suffering? Can anyone ever choose anything but an end to their suffering? The choice, if any, is already made; it always is.’

Steeped in Kashmiri folklore, The Last Knot is a story that sings.