Amritesh Mukherjee reviews The Hanuman Chalisa by Tulsidas, translated by Vikram Seth (published by Speaking Tiger, 2024).

भूत पिसाच निकट नहिं आवै।

महाबीर जब नाम सुनावै॥२४॥bhoota pisaacha nikaTa nahi(n) aawai

mahaabeera jaba naama sunaawaiThose who recite your name and your merit

– Tulsidas, Hanuman Chalisa, translated by Vikram Seth

Fend off every ghost and malevolent spirit.

I can’t tell you the number of times I would recite these lines (in Awadhi, of course) as a child: going from my room to the bathroom located in the verandah at six years of age, travelling through a dark lane to reach my home as an 8-year-old, crossing dark roads to pass off some item to my dad at 10, and so on. As thousands and lakhs of Indians, particularly in the northern and central parts of the country, I’ve grown up to hundreds of recitations of Hanuman Chalisa (while reciting yourself).

Recommended Reading: 14 Recommended Translated Poetry Books in India

And while I’ve left my religious and theist selves somewhere in the lanes of past tense, I can still recite the entire chalisa in less than 70 seconds (trust me, I just counted) with all the stammerings and slips in my muscle memory today. The point of all this is that it’s been a large part of my life growing up, and I’ve seen it being a large part of many around me.

But beyond the religious value of the text, why does the text remain relevant, easily the most popular chalisa (derived from the Hindi word, chalis, literally meaning forty, referring to the forty verses in these hymns) even after five centuries have passed since it was first written?

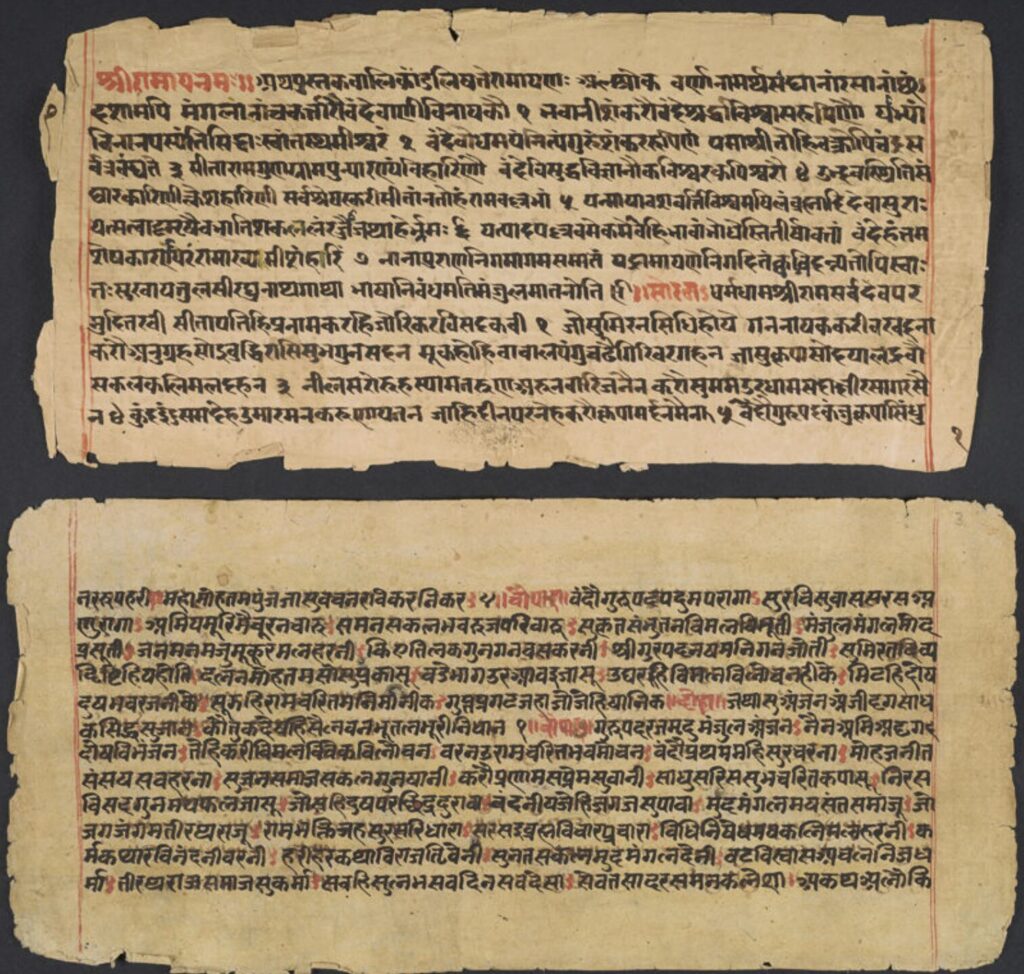

Bridging the Sacred and the Common Folk: The Story of Ramcharitmanas

Like many cultures, knowledge in ancient India, too, was limited to the elite. To read the Vedas, Upanishads, Ramayana, Mahabharata, etc., one required a solid background and understanding of Sanskrit, a language not usually spoken among the masses. Therefore, Tulsidas, also a scholar in Sanskrit but resolved to spread the knowledge contained in the Vedas, Upanishads, and Puranas, writing the Ramcharitmanas was nothing short of a watershed moment, naturally facing criticism of the contemporary Sanskrit scholars.

It popularized the Ramayana (and also the deification of Rama, which is a subject of discussion for another time) among the general populace and created yet-ongoing traditions like Ramlila. A bhakt or devotee of Hanuman, Tulsidas also wrote many odes to him, including the Hanuman Chalisa.

Recommended Reading: Unequal rhythm in Vikram Seth’s An Equal Music

Rhythms and Rhymes: The Poetry of The Hanuman Chalisa

As previously mentioned, a chalisa has forty verses. To accompany them, the Hanuman Chalisa also includes two dohas at the introduction stage and one to conclude the poem. Moreover, each line in a doha has three parts: one half consisting of 13 beats, a pause, and another half consisting of 11 beats.

However, in a chaupai or verse, each line has 16 beats divided equally into four parts. And, of course, each couplet has a rhythm and rhyme. To top it off, there are echoes, alliterations, and other poetic elements aplenty. There’s a delicious musicality to the poem, which allows it to be sung individually, in a group, or accompanied by the sounds of clapping and instruments.

From Devotee to Savior: An Ode to Hanuman

But, someone new to the text might wonder what the poem entails in the first place. Hanuman Chalisa is a hymn dedicated to Hanuman, the monkey god and one of the most celebrated deities in Hinduism. Tulsidas conjures images of the god in varying roles, from a devotee:

सब पर राम तपस्वी राजा।

तिन के काज सकल तुम साजा॥२७॥saba para raama tapaswee raajaa

tina ke kaaja sakala tuma saajaaRam, the sage king, reigns serenely.

– Tulsidas, Hanuman Chalisa, translated by Vikram Seth

All his tasks, you handle keenly.

a warrior:

आपन तेज सम्हारो आपै।

तीनों लोक हांक तें कांपै॥२३॥aapana teja samhaaro aapai

teeno(n) loka haa(n)ka te(n) kaa(n)paiYou alone can control your own fire;

– Tulsidas, Hanuman Chalisa, translated by Vikram Seth

The three worlds quake

when you roar out your ire.

Recommended Reading: A Suitable Boy by Vikram Seth

and a messenger:

सूक्ष्म रूप धरि सियहिं दिखावा।

बिकट रूप धरि लंक जरावा॥९॥sookshma roopa dhari siyahi(n) dikhaawaa

bikaTa roopa dhari lanka jaraawaaTiny in form—thus Sita discerning;

– Tulsidas, Hanuman Chalisa, translated by Vikram Seth

Awesome in form—setting Lanka burning;

to a healer:

लाय सजीवन लखन जियाये।

श्री रघुबीर हरषि उर लाये॥११॥laaya sajeevana lakhana jiyaaye

shree raghubeera harashi ura laayeYou brought the herb

– Tulsidas, Hanuman Chalisa, translated by Vikram Seth

that was Lakshman’s salvation;

Ram pressed you close

to his heart with elation.

saviour:

संकट कटै मिटै सब पीरा।

जो सुमिरै हनुमत बलबीरा॥३६॥sankaTa kaTai miTai saba peeraa

jo sumirai hanumata balabeeraFor those who seek him through meditation

– Tulsidas, Hanuman Chalisa, translated by Vikram Seth

Grief gives relief, pain liberation.

and a symbol of wisdom and knowledge:

बिद्यावान गुनी अति चातुर।

राम काज करिबे को आतुर॥७॥vidyaavaana gunee ati chaatur

raama kaaj karibe ko aaturDeeply virtuous, wise and clever,

– Tulsidas, Hanuman Chalisa, translated by Vikram Seth

Eager to serve Lord Ram forever,

As evident in the lines above, too, the poem also faintly describes the virtues of Ram whom Hanuman worships and serves. There are also allusions (something common in much of devotional poetry, specifically hymns and odes) to how reciting this poem regularly brings you knowledge, prosperity, and liberation from your sorrows.

Vikram Seth’s Translation: A Rhythmic Revival

Translating a poem with this many contexts and nuances, not to mention its poetic sensibilities, is no mean task. On top of that, to address the elephant in the room, at a time when religion, religious texts, and religious figures have been claimed and appropriated by violent groups and authoritarian regimes, Vikram’s text (and his brief yet delightful introduction where he dedicates the translation to Bhaskar, his character from A Suitable Boy, the boy who loved Hanuman and grew up to fight against intolerance) is a reminder of times and sentiments where religion and polarization didn’t need to be brethren and where religion and religiosity can be devoid of political affairs.

Before I stray too far away, let’s come back to Seth’s translation at hand. I’ve always admired Seth’s inclination to play with rhyme and rhythm in his poems and perhaps because of those same reasons, there’s a certain old-school charm to his poetry. That same charm lends itself greatly to the beauty of this translation, which is a valiant attempt at adapting not just the essence but also the musical quality of the original.

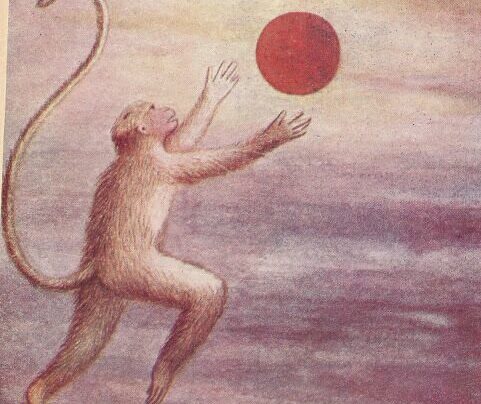

Take, for instance, this verse:

जुग सहस्र जोजन पर भानु।

लील्यो ताहि मधुर फल जानू॥१८॥juga sahasra jojana para bhaanoo

– तुलसीदास, हनुमान चालिसा

leelyo taahi madhura phala jaanoo

To take two separate translations:

The distant

– Devdutt Pattnaik, My Hanuman Chalisa

faraway sun.

You mistook

for a tasty fruit.

The sun is located at a distance of thousands and thousands of miles, yet you swallowed him taking to be a sweet fruit.

– Śrī Hanumānacālīsā by Gitapress

The focus, traditionally, has always been to convey the meaning and further add any contexts or layers of interpretations on top of it. Seth takes a different avenue. Apart from the introduction, the book comes without any notes or appendixes to provide any further clarifications or meanings. Hence, Seth’s translation of the above verse looks like:

Far in the distance, the Sun burned so brightly.

– Hanuman Chalisa, Vikram Seth

Like a sweet fruit, you just swallowed it lightly.

Do you see the light play of words? The sweet jingle of the sounds his lines evoke? There are several more (and perhaps better) examples to show the craft of Seth’s translation, but this little, playful verse works just fine. Seth doesn’t just want to reveal the meaning of Tulsidas’ original poem; he seeks to create an alternative for non-Awadhi, non-Hindi readers to find the same solace that millions of others have found in this poem.

Conclusion

Whether a devotee or not, whether someone belonging to Hinduism or even familiar with the faith and its myths or not, Vikram Seth’s The Hanuman Chalisa is a wonderful read. I call it Vikram Seth’s because despite it being a translation, anyone familiar with Seth’s works would find many characteristics of his poetic self here— not simply as a translator but as someone creating a classic work anew.