I remember the first time my grandmother taught me how to plant rice. I was nine. The school was closed for summer break. On the last day, I rushed home in excitement. I emptied the books from my school bag and packed them with the change of clothes. The next day, Mother dropped me off at the T-junction that leads to my village from the town.

“Listen to Āyi and Āwo. Be obedient to them and help them out with chores,” Mother entreated with great concern.

Mother packed a kilo of pork from the local butcher and bought yesterday’s newspaper. Today’s newspaper would only be made available tomorrow. It reads The Daily Newspaper, but we always get a day late in my hometown due to same-day-inaccessibility to the town from the city.

“Have the pork with Āyi and Āwo. They love it and make sure you give the newspapers to Āwo,” Mother said. She packed the pork and newspapers in my bag, standing at a corner in the street as we waited for Āni Chonmi. Mother’s friend from the village, Āni Chonmi, had come to the District Hospital for a health check-up, and she was returning to the village. So, my mother had arranged for me to travel along with Āni Chonmi to the village later in the afternoon.

My village is not very far from the town, unlike other long-distance villages. And if we take the shortcut, it is much closer. Āni Chonmi and I walked at moderate speed. We took a tea break in one of the tea hotels on the way. I had one boiled egg and pikhāchā. Āni Chonmi had bread toast. She paid for our tea.

On reaching the threshold of my village, the sun was about to set. Grandma’s house is just in front of the village football ground, the heart of the village. Grandma’s house looks majestic, with a canopy of huge and tall trees. I could see the sun rays beaming on the green tinned roof. The house has gigantic windows, which Grandpa saw in one of the English magazines and decided to build his house windows like one.

Āni Chonmi and I parted ways, and I hurried home to Grandma. I saw Grandma weeding her kitchen garden, which was just out front. I always found my Grandma working. I have never seen her stay idle.

“Āyi,” I screamed excitedly.

Āyi stood up, squinting as the sun was in her eyes, and called out my name.

“Penmi!”

“It’s summer break. I have come to spend the summer with you and Āwo. Where is Āwo?” I uttered rapidly, almost not allowing Grandma to speak.

“What a pleasant surprise. I am so glad to see you. Āwo is inside.”

Grandma ushered me inside after discarding the weeds that she had been working on.

I always look forward to the warmth of Grandma’s house. The fire had just been lit, and there was still smoke coming out from the fireplace. The soot-coated kitchen looked as welcoming as ever. As usual, I found Grandpa reclining on his huge cane chair and reading newspapers. He had his walking stick placed next to him like a sentry.

I put down my backpack, took out the newspapers, and went close to Grandpa. “Āwo, this is for you,” I said, handing him the newspapers.

For a moment, Grandpa looked at me blankly and said, “Ha?” I had forgotten Grandpa had a hearing problem. I moved closer to his ear, and this time, I spoke loudly enough to wake Gilli, the cat sleeping on Grandpa’s lap.

“Mother sent this newspaper for you, Āwo.”

“Very good,” Grandpa said in a loud voice in English.

“I was just telling your Āyi that I want to read a fresh newspaper.” Grandpa took it and shook my hands as he always does whenever we meet.

Grandpa was one of the first people to get an education in the village. He was always away from home because he worked as an education inspector while Grandma looked after their children in the village. Grandma, at the age of 18, had her first child and went on to have seven more children, out of which my father is the youngest. Grandpa, now retired, stays home with Grandma.

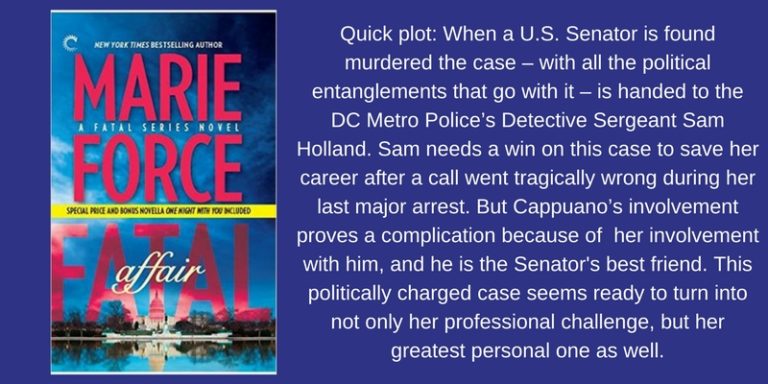

Recommended Reading: Manipur: Tour the Land of Gems through these books

“Āyi, mother sent this pork,” I said and handed the black polythene bag with pork to Āyi.

“Ringkaphā,” Grandma said as she stored the pork in the wooden cupboard away from the prying eyes of Gilli.

Grandpa has now turned on the radio. Grandma has started cooking rice. The fire is burning bright. The pork has been washed and chopped, ready to be cooked. I noticed that Grandma had taken out half the portion of pork and hung it next to the fireplace.

“Let’s smoke half and cook the other half,” said Grandma as she inserted a string on the pork for hanging by the fire. I was happy to see that Grandma saved half of it. Mother bought it with her hard-earned money. Unlike Grandma’s other daughters-in-law, my mother had no government job. She owns a small convenience shop, just enough to make both ends meet, and pork is expensive. I know that in my hometown, having a government job is equivalent to having everything. My parents have nothing except that my father does woodwork, and my mother opens a small convenience shop. But that was everything for me.

The fire crackles, and the hampai with pork is boiling away to its glory. Grandma prepared hot water in an aluminium basin for me to wash my feet. I soaked my feet for a while and washed them off with lifebuoy soap. Grandpa is making chutney for dinner. I believe that Grandpa makes the best kasātheinai in the entire world. Grandpa finely mashed a dried king chilli.

He roasted some dried river fish over the fire and added them to the king chilli chutney, mixing them with precision. He then took a spoonful of theisui from the bamboo case, which was placed next to the fireplace and added it to his chutney. My mouth watered. I was hungry and tired.

The cicadas have been buzzing and squawking. It is pitch dark outside. Moths swarm around the lighted candle on the table. There is something about the summer air in the village that I like. It’s warm, and you never know when the rain will come knocking.

After dinner, I helped Grandma do the dishes and make the bed. Grandpa would soon start snoring. Grandma was still moving around the room, getting ready for bed. Moths wouldn’t leave the lighted candle alone. I was exhausted from walking, and I, too, was falling asleep. Grandma blew off the candle and lay down next to me. The clouds began to rumble. It began to rain.

“Luisom is here,” uttered Grandma happily. I could feel that Grandma was happy to hear the rain patting on the tinned roof because I could see her put on a faint smile. Rain was everything for a paddy farmer like Grandma. Abundant rainfall brought good harvests, and rice plants needed enough water to grow.

The next morning I awoke at the sound of the cock crowing. It was bright but I could see fog scattered about from the window. Grandpa and Grandma were already up. I sauntered towards the kitchen, feeling half asleep but also feeling half awake. The fire has been lit, and the soot-coated kettle is on the fire. I looked outside and saw Grandma feeding the chickens in the barn just outside the house. The ground is still wet from last night’s rain, but the sun seems to be sneaking around amidst the fog. If coldness is to winter, uncertainty is to summer; one just can’t escape summer antics.

I dipped the katta biscuit that Grandpa got from the local grocer in the morning in my pikhāchā. I fed some soaked biscuits to Gilli. She purred in gratitude. Grandpa’s radio is blaring in full volume. With a mug of Horlicks tea in his hand, Grandpa is intensely listening to the radio. The sun has finally stolen the fog. It’s bright, and the birds are chirping.

After morning tea, Grandma cooked rice in a hurry.

“Penmi, you are coming with me to the paddy field today,” said Grandma.

I beamed in excitement as I washed the teacups. I have always wanted to explore paddy fields.

By 8:30 a.m., Grandma and I are ready to go to the paddy field. We had rice and last night’s leftover pork dish with boiled cabbage for lunch. In a sopkai, Grandma packed sugar and a batch of Kaziranga tea. She also put in the leftover katta biscuit and a bottle of drinking water.

“Penmi, fetch two steel cups from the shelf and put them in the sopkai,” Grandma said as she packed rice grains and sākao in a polythene bag.

“We’ll have rice and sākao curry in the afternoon at the field. Make sure to pack your change of clothes, too, Penmi.”

I packed some change of clothes and a bottle of drinking water in my school bag.

Grandma and I set out to the paddy field, walking as briskly as possible. We met other paddy fieldgoers as well. The sun was not scorching but rather mild. I could see dark clouds looming over the north. It began to drizzle and stopped when we reached the field. I love the summer aroma—fresh and unostentatious.

The little house at Grandma’s paddy field is a one-roomed space where there’s a fireplace in one corner. There are some old, worn-out clothes and bed sheets hanging in another corner of the house. We laid down our belongings, and Grandma began to get dressed for the rice plantation. She put on two pairs of socks on her feet and put on her camouflage-printed jungle boots. I picked up some old socks, which were kept on the wooden bench, and followed suit. I put on my worn-out canvas shoes. Grandma lit up the fire and placed some firewood. The smoke filled the room. She placed the soot-coated kettle by the fire and rose to her feet.

“Come, Penmi, let’s uproot the rice seedlings first, and then we’ll go into the field and plant them,” Grandma instructed me and led the way. I could see people working in their paddy fields close by. It was rice planting season, and everyone was working hard. Grandma took a bundle of rice seedlings and asked me to do the same. I followed her into the muddy field to plant rice.

“Listen, Penmi…see here. Take a seedling and push it inside the mud water with your thumb. Make sure it’s planted properly so that the rice plants do not fall.” Grandma taught me with intense enthusiasm as she continued planting them like a rice planting machine.

I took one rice seedling and did exactly what Grandma taught me. I pushed the plant with my thumb inside the mud water, and the rice plant stood strong.

“Look, Āyi, look… I have planted my first rice,” I rejoiced.

“You are doing very well, Penmi,” Grandma replied. She has already planted three rows of rice. I continued my new-found adventure in excitement. I bent down and started planting them as instructed by Grandma, but I was no competition for Grandma, for she was now at her fourth rice seedling bundle.

The mud in the field is slippery and soft. My rice bundle was almost getting over when I saw an earthworm crawling and getting inside the field. I got scared. I jumped in panic and ran out of the field. Grandma thought I got tired. She saw me getting out, and she asked me to go rest inside the hut.

“Don’t let the fire die. Put some firewood,” Grandma cried from across the field. I put in firewood and fanned it with a worn-out steel plate that Grandma used as a dustpan. I fanned the smoke into flames.

It was sunny when I came inside the hut, but when I looked outside after lighting up the fire, I saw dark clouds looming above the paddy field. And it began to drizzle in no time. The summer shower has begun. Grandma came running inside the hut. The heavy shower stopped, but the light drizzle had not stopped. Grandma rummaged through the metal trunk box inside the hut and took out a green-coloured plastic cover.

“Let me cook our meal when it’s raining now,” said Grandma.

Grandma rinsed the rice we had brought from home and put it in the rice pot. She added the sākao, crushed ginger, and salt to the rice and put it on the fire.

“This is how you prepare food in the field— the shortcut way,” Grandma declared as she stirred the contents.

“Oh, it’s not raining heavily anymore. Let me go and plant some more. You put down the rice pot once the water dries up and keep it near the fire.”

Grandma instructed and went out with the green-coloured plastic covering her body like a raincoat.

The drizzle did not stop, and Grandma was planting rice. I put down the rice pot and kept it next to the fire. It smelled amazing. The ginger and sākao aroma filled the hut now. The drizzle made everything look fresh. From inside the hut, as I looked out, I could see many rice planters. The rows of people bending down and planting rice looked like corn kernels on the cob. It looked amazing and picturesque.

In no time, Grandma came back to the hut. She removed her boots and sat by the fire. She inspected the cooked rice and put up the soot-coated kettle on the fire. She put sugar and tea in it.

“Penmi, get two steel plates from the trunk box. Let’s eat. I am famished.”

I took out the plates, and Grandma served the rice. The tea is also boiling. Just as we were about to eat, we heard someone calling us.

“Āni, oh Āni.”

A voice came from outside. It was Ānim, grandma’s paddy field neighbour.

“Oh, it’s you, Ānim; come inside,” said Grandma.

“I got some bananas for you. This must be your niece,” said Ānim as she looked at me.

“Yes, this is my niece Penmi. She’s come all the way from town to help me plant rice.”

Grandma introduced us as she took the bananas from Ānim.

“Thank you so much, Ānim. We are about to eat rice. Please take some of it too,” continued Grandma.

“No, it’s alright. My husband and I also had rice just now. Please enjoy the bananas,” Ānim replied as she exited.

Grandma and I had the most scrumptious afternoon meal. The mixed pot of rice and everything else tasted so good. We had pikhāchā right after and bananas.

“Oh look, Āyi, I got twin bananas,” I said in excitement as I flaunted a pair of bananas that stuck together like conjoined twins.

Grandma looked at it in bewilderment and took it from me and gave me a single banana.

“Give me this one. I’ll eat this. You eat a single one. If you eat these twin bananas, you’ll also have twins. It’s not good. Here, take this.”

“Twins,” I repeated after Grandma, puzzled and confused, but she had already peeled them and was already munching.

“You do the dishes. I’ll go ahead to the paddy field and continue planting.”

Grandma headed out with the green-coloured plastic in her hand. It was still drizzling.

By the time Grandma and I finished most of the work, the drizzle had stopped, but the sun was still hiding behind the dark clouds. It was not late, but the gloomy weather had made the day look late.

“Looks like there’ll be heavy rain anytime soon. Let’s head home quickly,” Grandma said. We started packing up our things. Grandma packed the washed pots and plates in the metal trunk box. I put the katta biscuit, uneaten, in my bag. With a walking stick in each hand, Grandma and I set off walking as swiftly as possible.

It was getting dark when we reached home. Grandpa was standing in the front yard waiting for us.

“Chinaongam’s mother, why are you guys coming home so late?” Grandpa said as soon as he saw us. “It is going to rain.”

My father’s eldest brother’s name is Chinaongam, and Grandpa would call Grandma not honey, not dear, but ‘Chinaongam’s Mother’. For the longest time, I had always thought Grandma’s name was Chinaongam’s Mother. But when I grew older, I learned that Grandma’s name is Luisomlā, and it didn’t make sense to me that people would call her Chinaongam’s Mother instead of her name Luisomlā.

Grandpa had lit the fire, and the water was boiling. Grandma began cooking dinner. After taking a bath, I helped Grandma prepare dinner.

“Oh, Chinaongam’s Mother, cook the dried fish for me. I want to eat that. Don’t put too much water, but put lots of ginger.” I could hear Grandpa telling Grandma while I took a bath in the bathroom.

During bedtime, Grandma prayed for me, and it felt nice. The rain is pelting left and right on the tinned roof.

“Āyi, why do you love paddy fields so much?” I asked Grandma.

“If you have rice, you are free from worries. If I have rice, I need not worry about what to eat next. Your grandpa was away for studies and work when our children were young, so I had to plant rice to feed the family,“ Grandma answered, reminiscing the past.

“I’ll make lots of money in the future and buy you many paddy fields,” I said and giggled.

It has been nineteen years since Grandpa left us from this world. Grandma is now 96, aged and bedridden. Once, a strong paddy grower, now stuck in between a bed sheet and blanket. Grandma’s house still stands majestic, except that it has become worn out and needs urgent whitewashing. The canopy of trees no longer adorns the compound, but the green-coloured tinned roof house still stands. The front yard looks deserted, devoid of life.

It is summer, and I am in my grandma’s home in the village. The village is now filled with concrete houses, but I remember seeing mud houses and tin-roofed houses. I will miss seeing buffaloes grazing on the village football ground. There were thick bushes of grass, and the ground looked lush. The village football ground is now wider and bigger, with no sight of grass.

The village church was a church in the wildwood, but trees no longer adorn its surroundings. Trees are being cut down, and they’ve abandoned the old wooden walled church and moved to a huge concrete church with a huge belfry installed just outside. All my childhood is gone with the village developmental projects.

And then there is Grandma’s house, worn out but cosy. We no longer use candles for light in the dark. We have electricity now. A film is playing on the television. I open the window to let the summer afternoon sun seep in. Grandma’s hair is all grey now. She is lying on her bed and watching television. I moved closer to her to put away strands of hair that were sneaking down on her face.

“Who are you? Don’t touch me,” screamed Grandma, looking at me fiercely.

“Go away! Don’t come near me!”

She began to jostle, trying to avoid my hands when I tried to clean her up.

“I am Penmi, Āyi, your granddaughter,” I answered. But she did not buy it and continued to scream hysterically.

My grandma, my Āyi, who used to work the hardest, is now senile and old. She recognises me sometimes but doesn’t most of the time. She can’t move without assistance. She is equivalent to a human vegetable. I look at Grandma and curse at the frailty of life. What a crumbly life we live! They say old age is an honour. But if I have to suffer like my grandma as I grow older, I’d rather live just up to my prime. Life is not fair.

Why does Grandma have to spend her last days in delirium? She has tilled the earth her entire life. Now, she lies immobile. It is raining; it is summer, the rice-planting season. Grandma would have rushed to the paddy field to plant rice if only she were as robust as she used to be in her prime.

The sun is slowly setting, and it will soon grow dark. Grandma lies asleep. I quickly prepare her dinner while she rests. When she wakes up, I feed her semi-liquid food.

“Oh Penmi, if it’s not for you, who would visit me like this,” Grandma said as she drank water with a straw from the cup in my hand. Grandma seems to remember me now.

“Āyi, why won’t I visit you,” I said as I put a spoonful of semi-liquid food in her mouth. Grandma ate her full. I cleaned her up and got her ready for bed. I let her nurse take a break for the night. It is dark outside. The cicadas are singing. I switched off the television and made my bed next to Grandma. The moths are hovering around the light bulb. Quintessential to summer, it began to rain, and the lights went off. Surely, the rice planting season has begun. Āyi’s favourite season has arrived.

The fog has just begun to fade away, and the cock crowed, heralding a new hopeful day. The ground is wet from last night’s rain. The morning sun spreads on the white calla lily plants, which grow in abundance in the front yard. Grandma, like a baby, is tossed away in her bed, sleeping like a log. I took a walk around Grandma’s house. The house looks tattered now, greatly in need of whitewash, but it still looks majestic with tall windows. I revved up the engine and took one last look at the house. It looked old and desolate but with memories of my childhood wound around in each pillar.

Next year, it will all be gone. Would the house still stand strong without Grandma? Who will take care of the kitchen garden that Āyi and Āwo adored so much? This would always be a mute inquiry that I’ll keep at the tip of my mouth. I know this would be my last summer in the village, and Grandma’s too.

Glossary

Āyi– grandmother in Tangkhul language

Āwo-grandfather in Tangkhul language

Penmi, Chonmi, Ānim, Luisomlā– Tangkhul female names

Chinaongam– Tangkhul male name

Pikhachā– Red tea

Àni– Aunt or Aunty

Hampai– black pottery, origin of Longpi Village, Ukhrul

Kasātheinai– ghost pepper chutney

Theisui– fermented soybeans

Luisom– rice planting season

Katta Biscuit– rusk

Sopkai– traditional utility hand-woven bamboo basket

Sākao– cured meat

Ringkaphā– expression of elation